Unframed is inviting curators with different specialties to discuss a single work of art or an exhibition on view. Today, assistant curator of Korean art Virginia Moon writes about the traditional and not-so-traditional influences on Korean-born artist Young-Il Ahn's work. Later, associate curator of contemporary art Christine Y. Kim will discuss Southern California's mark on Young-Il Ahn's practice.

Korean-born artist Young-Il Ahn (b. 1934) immigrated from South Korea to Los Angeles in 1966. He left at a time when the Korean art world was experimenting with monochrome styles known as dansaekhwa, as well as versions of American abstract expressionism and European abstract expressionism known as art informel. Initially, because South Korea was still experiencing serious economic hardship, having emerged from 35 years of Japanese colonization (1910–45) and another three years of civil war (1950–53), Korean artists were only able to discover these Western styles through Japan, as Ahn had been able to during his childhood in Japan. It was only many years later that most Korean artists were able to access examples of these Western art styles directly through U.S. and Europe.

As a result, Ahn’s earlier works, when he first arrived in the U.S., possessed an art informel style, abstractly depicting subjects he loved—landscapes, birds, and musicians. Scholar Youngna Kim explains that American and European versions of abstract expressionism held an attraction for Korean artists, as the styles allowed painters to incorporate their individual sense of Eastern philosophy into the works. For Ahn, a promised contract with the Zachary Weller Gallery, formerly on La Cienega Boulevard, provided a guaranteed platform to show his works, which prompted his trans-Pacific move from his homeland, with family in tow. With easy access to all the paints and canvases he needed for the first time in his life, he had no intention to return to Korea and decisively chose to continue his now-50-plus-year career in Los Angeles.

In July 1983, everything changed for his artistic style. While out in a fishing boat in Santa Monica, Ahn was suddenly caught in a dense fog, and he could not see anything around him, including his hands. Ahn always loved the water and the fog did not change that, but the minor traumatic event solidified what would be a decades-long passion—to try to capture the infinite ways the ocean looked when the fog lifted.

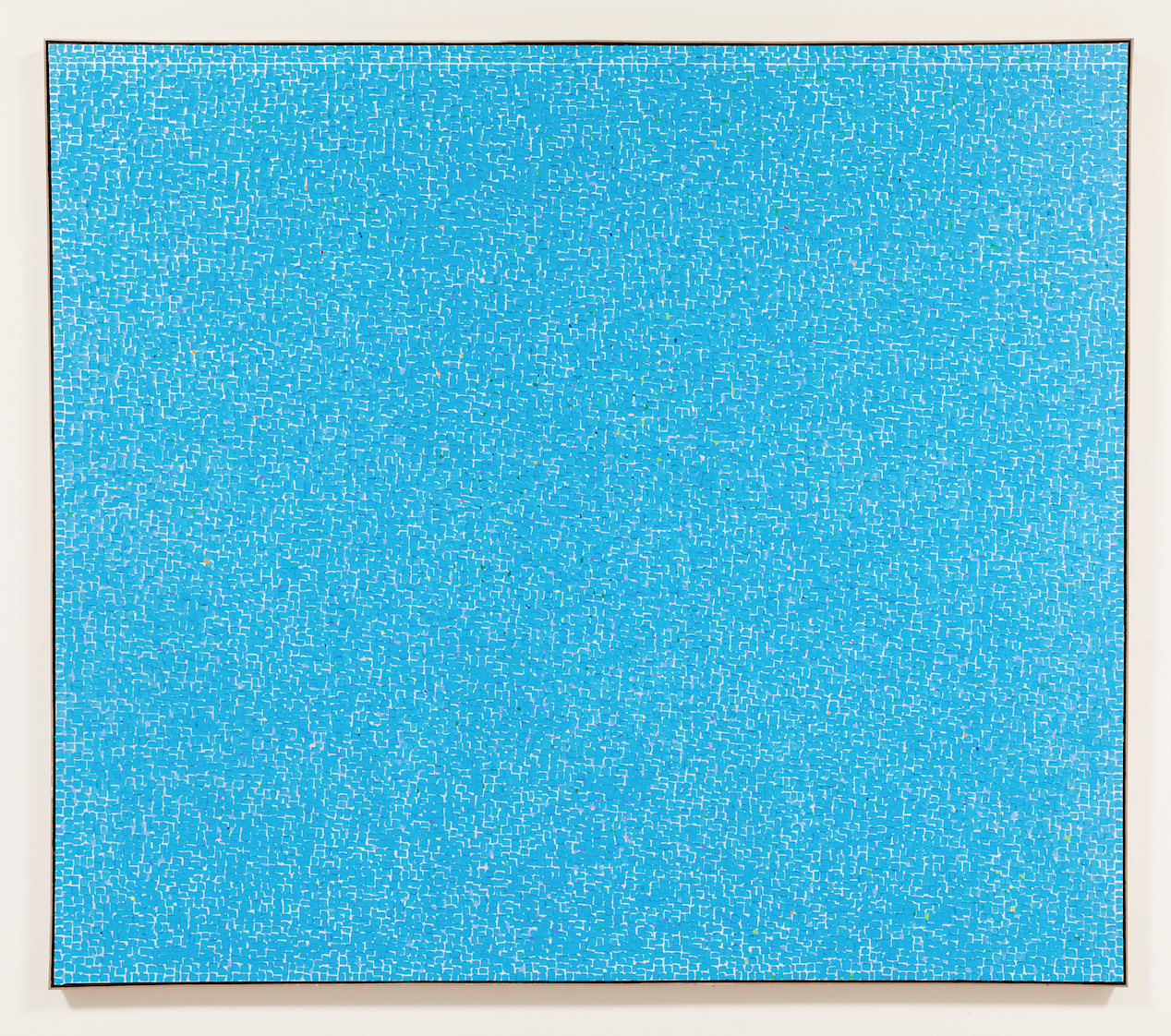

His painting, Water SZLB15, currently hanging in the Korean galleries at LACMA, is part of Ahn’s Water series. From a distance, his paintings look to be of a single solid color, but when observed up close, you see different colors hiding behind the multitude of ordered, small squares. It is an ongoing series inspired by this event in 1983 and has been produced in a multitude of colors. His works have been most recently exhibited in a solo exhibition at the Long Beach Museum of Art, Memoir of Water (2015), Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles (2015), as well as many notable galleries in Seoul, Korea, including Gallery Hyundai.

His works are an anomaly—how does Ahn’s works fit into the corpus of Korean art history? Renowned Korean art critic Jin Sup Yoon refers to Ahn’s paintings as dansaekhwa. Dansaekhwa, which literally translates as “single color painting,” is a difficult Korean art style to pin down precisely, or concretely, as it was not an official art movement nor an art collective guided by a manifesto. As the name suggests, most paintings of this style are monochrome, but not all. There is an implied acknowledgement and expectation of a spiritual process experienced by the artist and a keen conscientiousness of the materials used. Beyond these generalities, each artist has claimed his own method, style, and presentation. Works that have been associated with this style, all from the late ’60s and ’70s in Korea, are now experiencing a notable revival recently, both in South Korea and internationally.

But Ahn’s Water series style, while bearing similarities to his more definitive dansaekhwa counterparts, was borne of a single incident, in 1983, after over three decades of residing in the U.S. where he was exposed more to both local and American artists than Korean artists. His style, while undeniably abstract, is his own, and as such, his works represent a new trend in the corpus of Korean art history. In this way, I would argue that Ahn is a breed of Korean artist who was not actively exposed to the tribulations of his fellow early contemporary artists in Korea as it was developing and gaining momentum, nor its reactive political originations, both of which also define the tenor of dansaekhwa art. Rather, like the many international contemporary Korean artists today, like Lee Bul, Kimsooja, Yeesookyung, and Gimhongsok (whose works are currently in LACMA’s collection) who live abroad and have shows in different foreign countries, Ahn was a pioneer in this regard. He set the trend for the diaspora of Korean art.

Young-Il Ahn's Water SZLB15 is currently on view in LACMA's Korean art galleries.