Carlos David Almaraz was born in 1941 in Mexico City. About six months later the Almaraz family moved to Chicago, where he spent much of his childhood. The family moved to Southern California, eventually settling in East Los Angeles when Carlos was about ten. After graduating high school in 1959 he studied briefly at Loyola University of Los Angeles and California State College, Los Angeles, and then for about two years at Otis Art Institute. In 1962 Almaraz moved to New York; after about six months Almaraz returned to Los Angeles to resume his education at Otis and, briefly, at University of California, Los Angeles. The East Coast, however, continued to beckon, and in 1965 he returned again to New York City, where he lived and worked for five years. Almaraz arrived as an aspirant figurative painter in New York during the ascent of minimalism and conceptualism. His aesthetic sensibilities were not merely out of keeping with the newly ascendant minimalist tenor in New York but were emphatically antithetical to it. His work found little traction, aside from participating in a group show at the Terrain Gallery.

Almaraz returned to Los Angeles in 1970, haunted by feelings of disappointment and defeat. But coming home did not soon bring the restoration he’d no doubt hoped for. In fact, he would endure a near-total undoing in early 1971 that resulted in his being hospitalized for more than six weeks, much of it in a drug-induced coma. His near-death experience in the hospital changed the trajectory of both his art and his life. During his recovery, through his friendship with fellow artist Gilbert “Magú” Luján, Almaraz engaged for the first time with the political and cultural issues of chicanismo, a movement to recognize and honor the experience of American residents of Mexican heritage. By 1972 Almaraz was active with the farmworkers’ causa, led by union activist Cesar Chavez, painting banners for rallies and creating backdrops for playwright-director Luis Valdez’s Teatro Campesino (Farmworkers’ Theater). Instead of working in a private visual language, Almaraz found himself crafting visual manifestos for a social revolution, helping to expose the near slave-like conditions endured by migrant agricultural laborers.

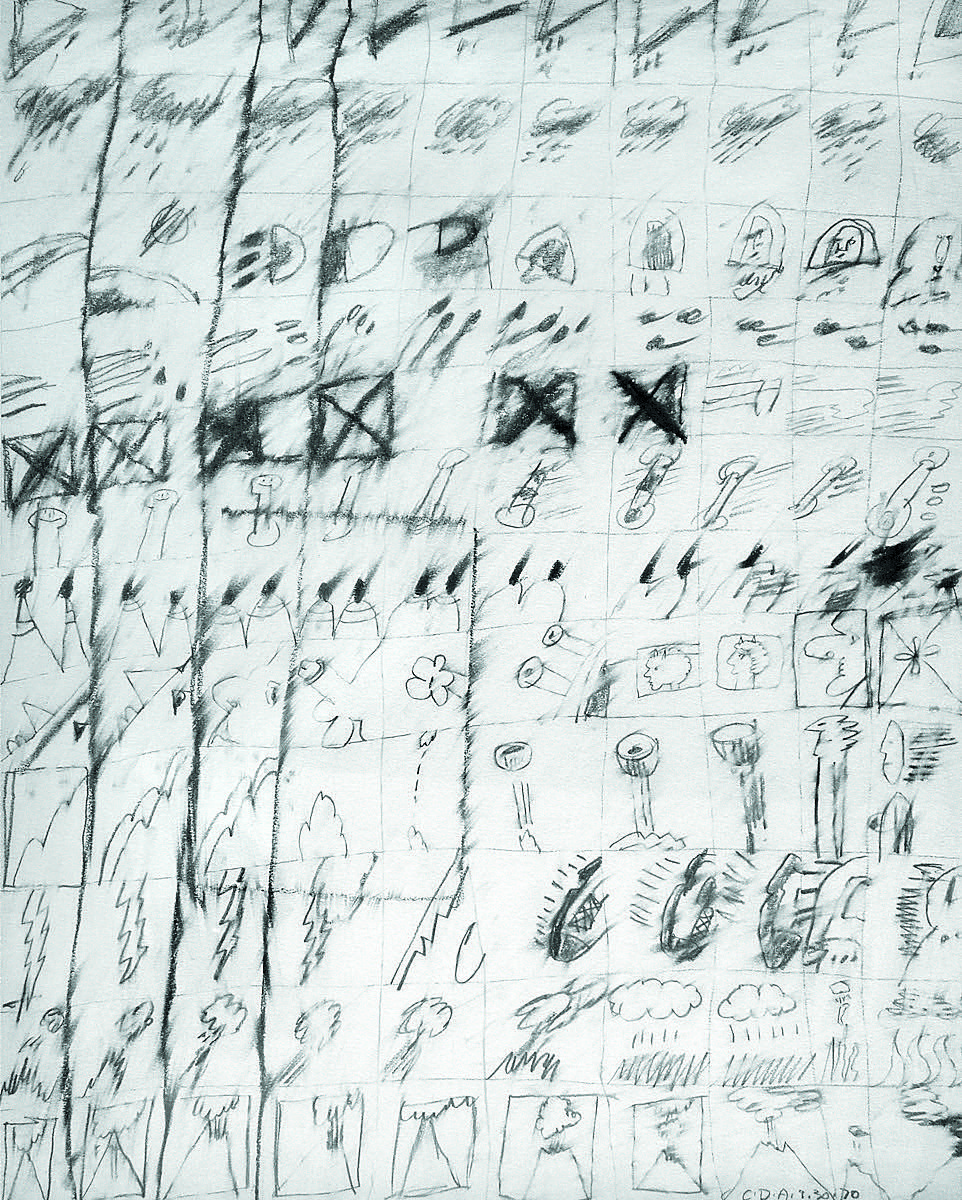

In tandem with his political activism, Almaraz also pursued his artistic interests within the growing Chicano artists community, and with Luján, Frank Romero, and Roberto “Beto” de la Rocha, he cofounded Los Four in 1973, one of the first Chicano artist collectives. More than a confederation of like-minded artists, they frequently collaborated with one another, sharing an interest in both muralism and graffiti and adapting techniques of street art for their own artistic projects. Los Four stood as a united front against the popular conceptualization of the artist as an enlightened genius, a visionary fundamentally different from regular folks, and as a creator of masterworks to reflect eternal truths. Their first public exhibition was at University of California, Irvine, in November 1973. A greatly expanded version of the show, comprising nearly 200 works, was subsequently staged at LACMA in 1974, the first exhibition of the work of Chicano artists presented by a major museum.

Not surprisingly, the radical social engagement of the Mexican muralist tradition was both a political and an artistic inspiration for Almaraz. During Mexico’s post-revolutionary era in the 1920s–30s, artists such as David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco advocated for a national political, social, and cultural unity through their monumentally scaled works glorifying the country’s ancient history, its heroes, and of course, its independence. For Almaraz, muralism was part of a broader rejection of private art, leaving behind the studio to participate in public venues, and proffering his cultural work—both as a gift and as an entreaty—to a broader audience in order to share fundamental social visions and beliefs.

This stance in favor of public, politicized art contrasts startlingly with the highly personal studio practice that would ultimately prevail for him. Almaraz’s proselytizing for Chicano political power and cultural pride demanded a deep inner commitment as well as a more public, community-based activism. But this contrasted, and perhaps even conflicted, with his interest in European art and art history, originally sparked by his academic studies and deepened through his travels in Europe and elsewhere. There was an inherent tug of war between his self-appointed mission as a public artist and his desire to nurture his inner artistic impulses.

After resigning from Los Four in 1979, Almaraz essentially began a second artistic career as a studio artist. As his work evolved, it became ever more psychological, dreamlike, even mythic and mystical. Removed from the public art milieu, Almaraz soon attained notable commercial and critical success as a solo artist through exhibitions at prestigious galleries. In the end his return to the studio was less a retreat from his artistic aspirations than it was a resolution or reconciliation of his inborn motives as an artist.

Following his rethinking of his own motives and aspirations, his work shifted markedly from his Chicano advocacy to a far more introspective mood that was nuanced and often ambiguous. His new personal art still depicted the sights of daily life of Los Angeles, but now they became deeply interior, indeterminate, and more illustrative of his inner musings than of communally shared understandings or experiences. It became more complex in its inspirations and sources, heavily influenced by both his Eurocentric art training and a deep and abiding interest in ancient Mesoamerican cultures as well as his own mandate to depict contemporary urban life and popular culture.

On October 8, 1981, three days after his 40th birthday, Almaraz married Elsa Flores in Cancún, Mexico. About a year and a half later their daughter, Maya, was born. In 1987 Almaraz learned that he had contracted HIV. From that time onward, his art reflected the gamut of emotions as he faced his mortality. He remained loyal to his favored themes, but addressed them in newly modulated tones. His characteristic palette of highly saturated colors now sometimes shifted to a darker, duskier gradation, and his content was often overtly about death and destruction, but just as often could be contemplative or triumphant.

Almaraz died in 1989, at age 48. Nearly 30 years later, he is still routinely identified specifically as a Chicano artist. But while it is important to acknowledge his undeniable role in championing a visual art that pronounced itself as uniquely Chicano, Almaraz in fact straddled multiple and often contradictory identities that drew from divergent cultures and customs. He was a true mythologist, ultimately believing not in the primacy or the uniqueness of any particular group but rather in the universality of the human imagination. Rather than cultural separateness or essentialism, he embraced crossover and hybridity. Carlos Almaraz emerges today as an exemplar of open-mindedness, of personal curiosity about human experience, of anybody’s fundamental interest in sharing, in imaginative participation, and in the exploration our commonality manifested through art.

This post is adapted from the exhibition catalogue. Playing with Fire: Paintings by Carlos Almaraz opens in BCAM on August 6. Member Previews begin today, August 3. Join now to experience this exhibition before it opens to the public! Playing with Fire: Paintings by Carlos Almaraz is part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, a far-reaching and ambitious exploration of Latin American and Latino art in dialogue with Los Angeles.