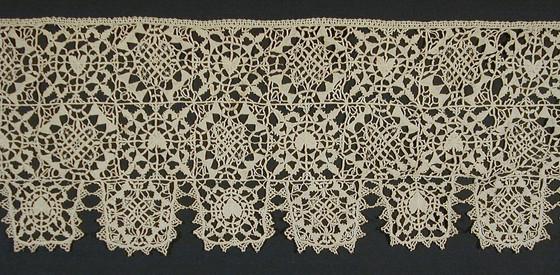

In the exhibition To Rome and Back: Individualism and Authority in Art, 1500–1800 (June 24, 2018–March 17, 2019) hangs a length of linen needle lace that was constructed stitch by stitch with needle and thread. It truly is a length, measuring 138 ¼ inches long, fitting its frame only when rolled on both sides. Fully extended, the lace reads like a timeline beginning with its creation in Italy in the early 17th century. The lace’s posterity in LACMA’s collection indicates another moment in its history: the Italian initiative to revive the nation’s lace industry, three hundred years later, following the country’s unification in 1871.

Unrolling this revival, called the neo-Renaissance, reveals its scope as a national effort to reorganize Italy’s artistic and industrial education systems with the goal of training architects, artists, designers, and producers in a unified design tradition. The story of the Italian lace revival is found in the workshops of The Burano Lace School and Aemilia Ars; in the pages of Italian fashion magazines; and in the wardrobe of Queen Margherita of Savoy. The early 17th-century linen needle lace featured in To Rome and Back would have been highly desired during the neo-Renaissance, which lasted from the 1870s into the early 20th century, as an antique lace to be studied and reproduced by Italian lace-makers who were newly trained in old traditions. Women—from the lace-makers of Italy to the Queen of Italy—are key characters in this story, contributing to the revival as producers and promoters of lace and its labor.

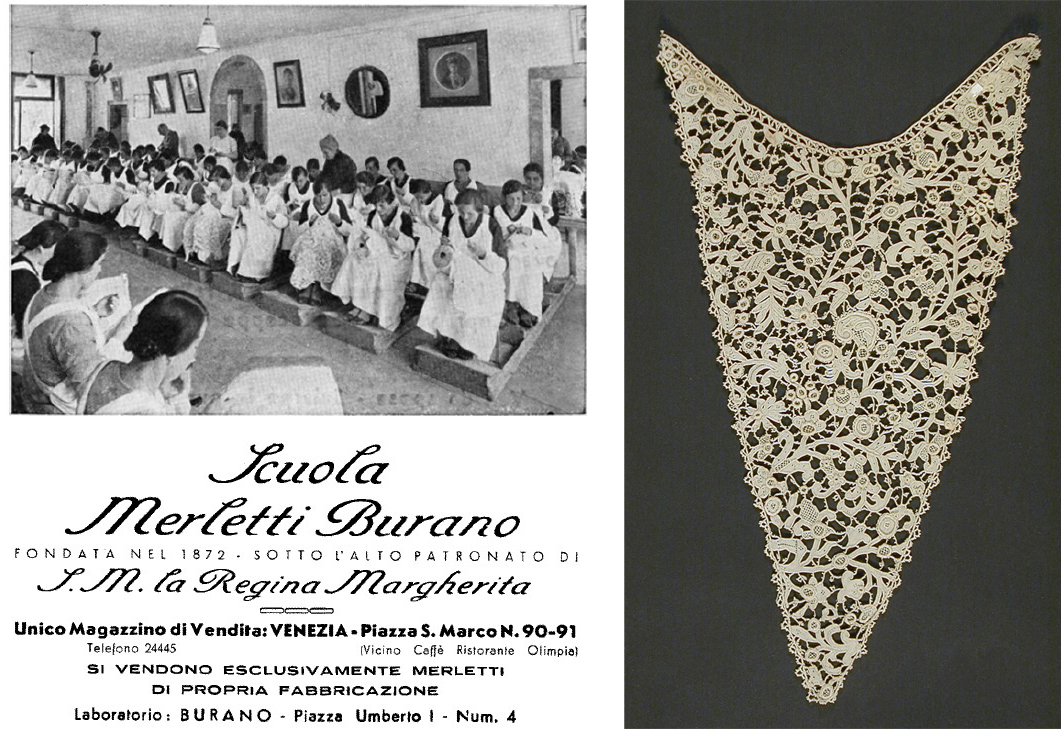

By the the late 19th century, Italy’s lace industry was in an overall slump; so much so that it took government backing and aristocratic patronage to revive it. The Burano School of Lace (Scuola Merletti Burano) was founded on just that. The School was established in 1872 by Contessa Andriana Marcello as a philanthropic organization to ease economic hardship after the collapse of the island’s fishing industry. What began with one woman, Cencia Scarpariola, who knew how to make traditional Punto di Burano needle lace, grew to 600 women by the year 1900. Crown Princess Margherita of Savoy became the School’s official patron in 1874, providing funds as well as Renaissance laces from the House of Savoy’s royal collection. These antique laces were faithfully copied by the women of the Burano Lace School, collectively securing the revival of Renaissance lace as well as Burano’s local economy.

Bologna was another center of lace revival led by Aemilia Ars (Società Cooperativa Aemilia Ars), a design company founded in 1898 by the architect Alfonso Rubbiani and overseen by the Contessa Lina Cavazza. Rubbiani was inspired by England’s Arts and Crafts movement, adding to it a distinctly Italian Renaissance flair. The company’s woman-made lace and embroidery division met such success that it outlived the greater Società Cooperativa, becoming the Aemilia Ars Cooperative of Lace and Embroidery in 1903. Aemilia Ars laces and embroideries went on to earn numerous awards at national and international exhibitions, cementing neo-Renaissance lace as a prosperous industry and a desirable fashion commodity.

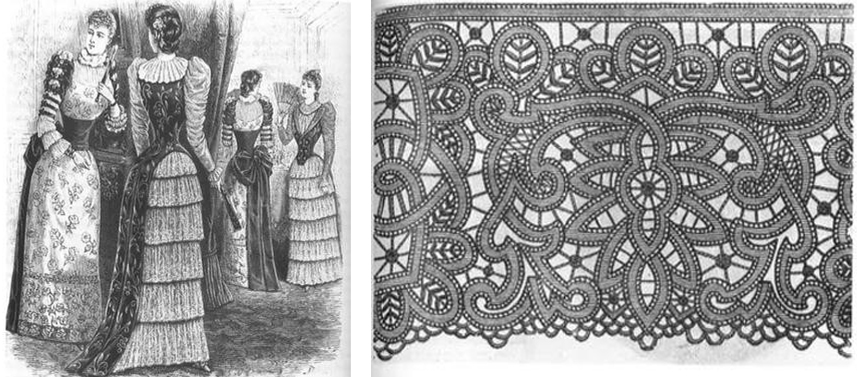

Fashion for neo-Renaissance lace is found in fashion periodicals and designs of the time. Queen Margherita of Savoy, who reigned over Italy from 1878 to 1900, was its greatest influencer. In addition to funding and relaunching the production of Renaissance needlepoint laces, Queen Margherita’s Renaissance-inspired fashions were richly adorned with precious laces. The fashion magazine Margherita reported on the Queen’s ball gown worn to inaugurate Turin’s 1884 Exhibition of Industry and Fine Arts (that included works from the lace revival industry), noting the gown was completely covered in Renaissance lace belonging to the House of Savoy and displayed “all the ingenious ways in which antique lace can be used in modern style without making a single cut to it.”

While reporting on the Queen’s fashions and laces, Margherita also used its platform to strongly support Italy’s vocational schools dedicated to lace revivalism, further intertwining the revival lace industry, the neo-Renaissance style, and the lace-loving Queen. The Queen’s garments and laces were translated into simplified clothing models and Renaissance lace reproductions, making both accessible to the nation’s expanding female readership and neo-Renaissance fashion followers. Some precious antique laces, like the needle lace in To Rome and Back, were adapted to suit contemporary fashion. Renaissance lace fragments were reconstructed as collars and hems while intact ones were lengthened by widening the voids in their design. Reproduction laces—like those made by the Burano School of Lace and Aemilia Ars—filled in the gaps, amounting to an available vogue for dressing oneself in past while unifying the present.

Italian women inspired by Renaissance lace played an essential role in consolidating and promoting the newly unified nation. Examples of its impact are found in LACMA’s own collection, including a recently acquired woman’s cape by Maria Gallenga (1922) with Renaissance motifs and a high collar and a woman’s ensemble by Mariano Fortuny (c. 1927) that features a gold-stamped lace pattern. Turns out the history of the linen needle lace in To Rome and Back is much longer than it looks.

Make sure to follow @ToRomeandBackLACMA on Instagram for more!