Three years ago, I was fortunate enough to participate in my first archaeological excavation. This was an exciting time for me as a non-traditional student; I never imagined I’d end up back in school, much less taking an international trip alone to realize my far-fetched dream of becoming an archaeologist.

The site director Rui and his colleagues could easily trace back nine generations’ worth of personal family history in the region of Portugal we were excavating, so a sense of responsibility and stewardship was quickly felt by our group. He explained on the first day that we were about to embed ourselves in the life of the site; whatever and however we moved on this land would be incorporated into the place’s long and storied history. For the first time in my undergraduate career, I was confronted with the idea that my position as a researcher and academic will never be objective. I had arrived worrying about proving myself in the field, so the realization that I—some community college kid from South Central L.A.—was about to join Roman soldiers, plague victims, and the ancestors of the local community as part of the life of the land completely transformed how I viewed archaeology and my place in the world.

This awareness has come to inform how I experience art, especially since joining LACMA as a Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow. I gravitate to questions about context: What is the life of an art piece, or the life of the idea that it represents? How has its functionality and significance changed across time and space? How is that encoded into its visual language—or at least, our interpretation of it? This has been an interesting exercise when it comes to Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads, which was recently re-installed at LACMA for Legacies of Exchange: Chinese Contemporary Art from the Yuz Foundation.

Ai Weiwei created large-scale reproductions of fountainheads that once adorned a clepsydra, or water-clock, in Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace). Standing between 9 and 11 feet tall, the zodiac heads are held up by long, slender columns that resemble moving water. At first glance, they are simply the familiar animals of the Chinese zodiac. Beneath the surface, however, they embody the continued life of the original fountainheads as highly politicized icons of Chinese heritage.

Their story starts in the early 18th century, when the Italian Jesuit missionary Giuseppe Castiglione arrived in Beijing. Though he arrived in China during a time of contention between the imperial court and the Christian church, the Qing emperors appreciated European contributions to astronomy, cartography, engineering, art, medicine, and diplomacy. Castiglione’s ability to marry Western styles to Chinese themes was well received by the three emperors he served throughout his life—the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors—whose attraction to European art was due in part to its novelty and exoticism in China.

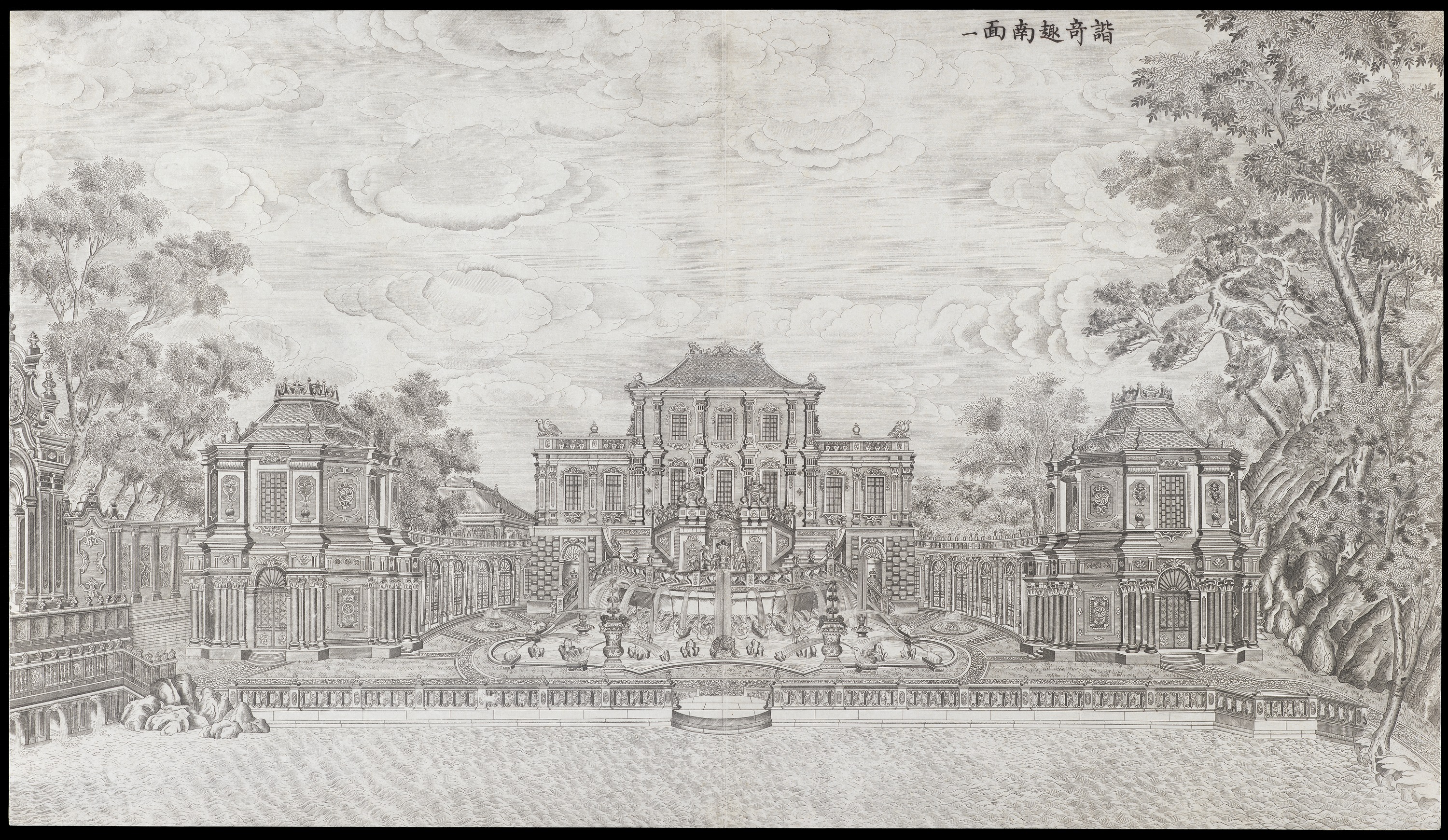

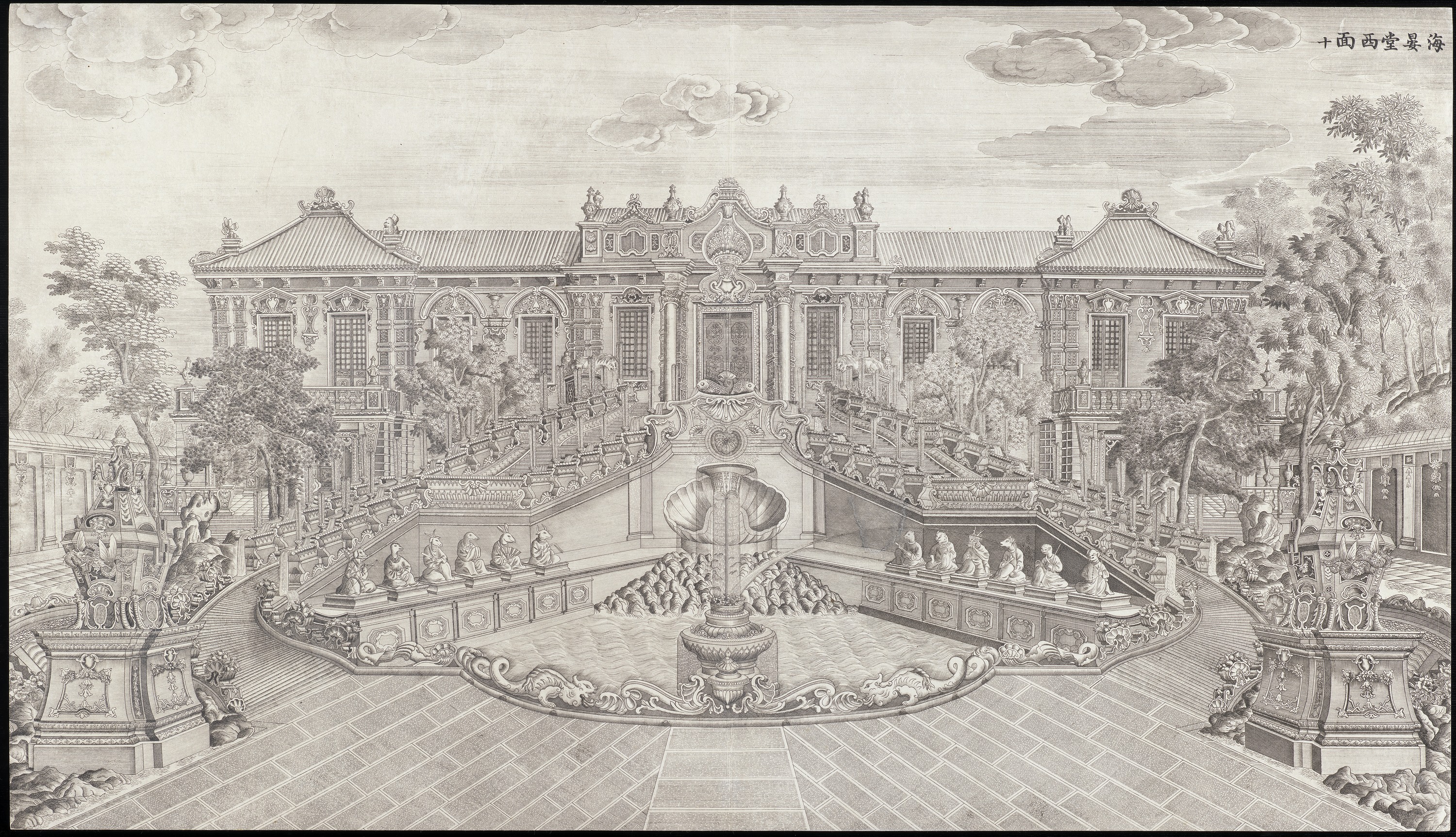

Though primarily a court painter, Castiglione was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor in 1747 to design the opulent Xiyang Lou (Western Mansions) in the northeastern corner of the otherwise Chinese-style Yuanmingyuan—a broad complex of mansions and gardens that eventually became the main political center and living quarters for the imperial family. He and other artists designed the Xiyang Lou in a late Baroque style that was reminiscent of the palace in Versailles. Among his many contributions to Yuanmingyuan, Castiglione designed the Haiyantang (Hall of Calm Seas) in collaboration with a fellow Jesuit—a French engineer by the name of Michel Benoist—and skilled Chinese craftspersons. This addition to the pavilion included the clepsydra on which were mounted the iconic fountainheads that depict the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac.

The statues were bronze-plated animal heads with robed anthropomorphic bodies made of stone. They lined the clepsydra in a half-circle and would each spout water from their mouths in two-hour intervals. The twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac are an integral part of traditional Chinese measurements of time; each animal is assigned not just a year that corresponds to the movement of Jupiter across twelve stations in the sky, but also a month, week, day, and shi of the day, a unit of time that is equivalent to two Western hours (see East and West, Past and Present: Ai Weiwei’s Zodiac Heads). The fountainheads adorned Yuanmingyuan until 1860, when French and British military forces arrived in Beijing during the Second Opium War. Yuanmingyuan was destroyed and many of the imperial family’s objects were looted and dispersed. Today, only seven of the twelve original fountainheads are known to survive.

The Opium Wars are the first in a long series of events that constitute the Century of Humiliation, a term used in China since the early 20th century to describe the relentless barrage of foreign aggression done unto them by Western powers, Russia, and Japan. The end of the Century of Humiliation is open to some interpretation. It has been declared over several times in the past during significant moments of Chinese history, but expanded whenever China is criticized. This is part of a strong sense of nationalism in China that has further manifested in the retroactive application of a political narrative onto items looted from the Yuanmingyuan.

Notably, the original fountainheads circulated in the art market for decades; two of the fountainheads appeared at an auction in 1987, and three again in 1989, but they received little attention from Chinese collectors because they were not yet the revered symbols of Chinese cultural heritage that the art world recognizes them to be today. It was by sheer coincidence that the tiger, ox, and monkey fountainheads resurfaced at an auction in Hong Kong in 2000. The association between the recently repatriated (in 1997) Hong Kong and the fountainheads enveloped the objects in the high level of public awareness and nationalist discourse that was already taking place at the time. Since then, any further auction of the fountainheads has been protested with calls for repatriation. When protests are ignored, Chinese collectors—often called “patriotic collectors” and “national heroes” in the media—have purchased the fountainheads and donated them to the Chinese government.

Though now famously centered in a global discussion of repatriation, there is no consensus within China about how to proceed. Debates rage over whether the fountainheads are world heritage, Chinese heritage, both, or neither. Many take great offense to their commodification, even criticizing patriotic collectors for ultimately remaining complicit in the sale and price inflation of national cultural patrimony. Others—including Ai Weiwei—question whose nation is truly being celebrated when the original fountainheads were designed by Europeans, reflect European aesthetics, and were commissioned by the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty, who conquered China in the mid-17th century. He further calls attention to the erasure of communism’s role in the destruction of China, claiming it disingenuous of the Chinese government to place accountability of the destroyed Yuanmingyuan squarely on imperialist forces.

Ai Weiwei’s Circle of Animals/Zodiac Heads continues the story of the original fountainheads by not only referencing, but also building upon its history through thoughtful changes and subversions of the original designs. The columns that resemble jets of water reference the function of the original fountainheads, but their imposing size speaks to their growing attention. He recreates the likeness of the tiger head—even when the original resembles a bear, as tigers were unfamiliar to the European Jesuits who made it—but he also fills in the gaps when it comes to the five heads that are missing by imagining his own. By creating this new event in the life of the fountainheads, the artist skillfully connects the past to the present, not in spite of the objects’ political and cultural turmoil, but because of it.