Cactoid Labs curator and co-founder Lady Cactoid recently sat down with artist Monica Rizzolli to explore her process, the stories behind the art she currently have on view on the LACMA's Stark Bar screens, and the work she is creating in dialogue with the museum's permanent collection for the project Remembrance of Things Future, curated and engineered by the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs.

Building upon LACMA’s historic engagements with Art and Technology, Remembrance of Things Future is an invitation to travel via the blockchain back in time through the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Utilizing tools such as generative code, dynamic software, artificial intelligence, and video synthesizers, Monica Rizzolli, alongside other pioneering artists, has been invited to select objects from LACMA and make new digital editions inspired by the museum’s holdings. Released on the blockchain in phases beginning in March 2023, a percentage of proceeds from these limited Remembrance of Things Future digital editions goes to support LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. More information on this project can be found at lacma.cactoidlabs.io.

Hi, Monica! Can you speak a bit about how you began your artistic journey and when you began using code to create art? What possibilities does code present as a medium and tool that excites you?

My grandfather had a print shop where he was a typographer, and I always loved to look at the stereoplates and printing machines. Then as a teenager, I decided to learn woodcut and lithography, and soon after started to study visual arts at university in Brazil. Since then, drawing has become my favorite medium for understanding the world. In 2012, I attended the University of Kassel as an exchange student and wanted to draw landscapes that change over time. I discovered the Processing language and learned how to code by myself. In 2015, I presented my first generative simulation at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles. There, I started to learn about generative aesthetics and became fascinated with creating a system of rules to produce art. It was not a new idea; artists dealing with analogical mediums have done this before. However, the computer can quickly iterate through much more complex commands, and the results often surprise me. It is liberating to give some control of the creative process over to chance.

I know you recently moved to Portugal, but you are originally from Brazil and there is a deep connection we see to Brazilian flora and history in your work. We see that in the Tropical Garden series triptych that is currently on view on LACMA’s Stark Bar screens. One piece from that series, entitled Tibouchina mutabilis, death, recently entered LACMA’s permanent collection through digital art patron Cozomo de’ Medici’s generous gift of blockchain artworks to the museum. What is that series about?

Two things drove me to flora. The first was its morphology and how shape and structure develop; this is a formal and mathematical aspect of plants. Secondly, looking at plants can teach us a lot about a place, what people eat, where the plants came from, their symbolism, and so on. These are social and historical aspects of flora. So, I looked at Brazilian flora to understand where and how I was in that environment, which is how Tropical Garden was born. The fact that part of that series is now part of LACMA’s collection is an enormous honor.

There is a rich history of computational art in Brazil. That history comes through in LACMA’s current exhibition Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982, which includes the work of Brazilian artist Waldemar Cordeiro. Do you see a lineage with that past and your own work?

Waldemar Cordeiro was part of the Brazilian Concrete movement, chasing ways to structure images through language and quantitative methods. Another influential Concrete writer, Haroldo de Campos, translated Max Bense's "The Projects of Generative Aesthetics” to Portuguese in the ’60s. How important was that to Waldemar? A few years later, he developed with the engineer Giorgio Moscati the series Derivadas de uma imagem, a generative process of translating a figurative image to computational language, combining structure with semantics. Another artist of this group, the Spanish artist Julio Plaza, was researching semiotics and digital mediums. Later, he wrote Os Processos Criativos com os Meios Eletrônicos: Poéticas Digitais, with Mônica Tavares, an influential book for me. So, I see myself as part of this lineage.

Can you tell us about the works you have taken inspiration from in LACMA's collection for the blockchain initiative Remembrance of Things Future?

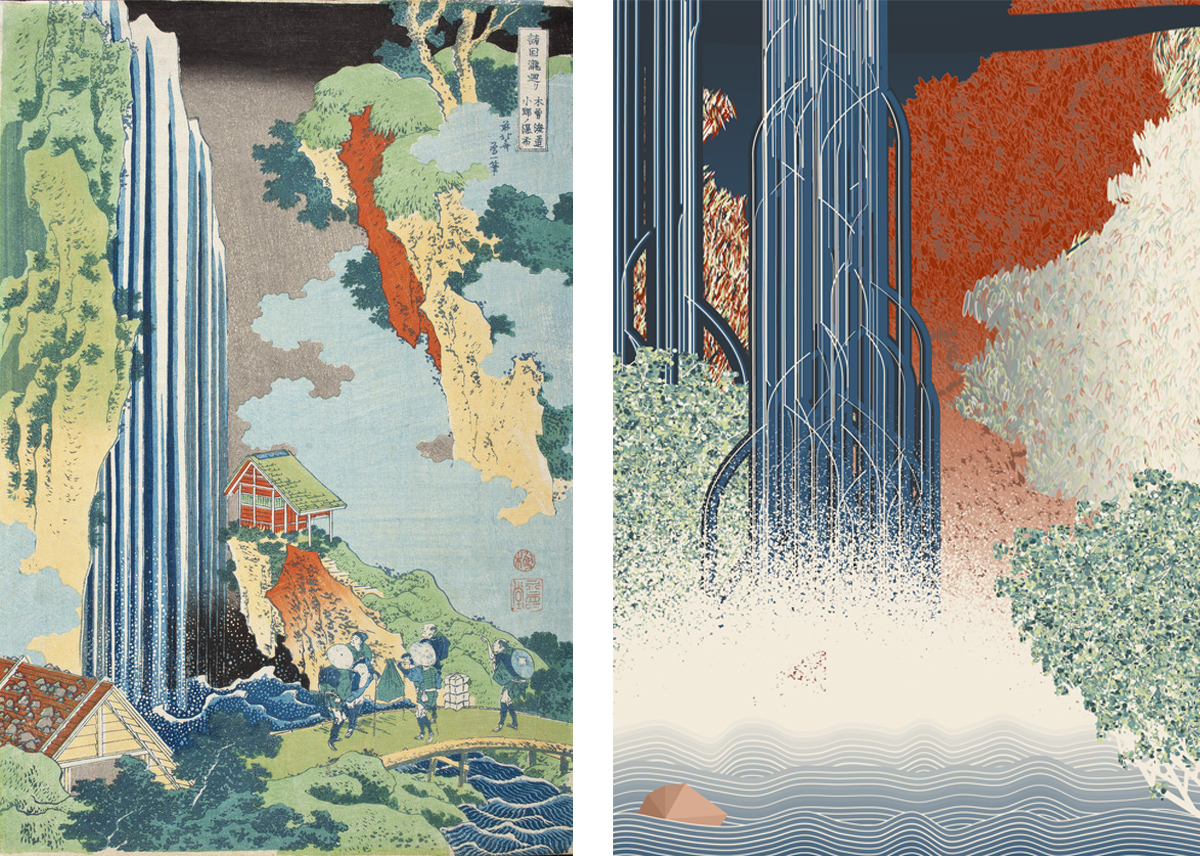

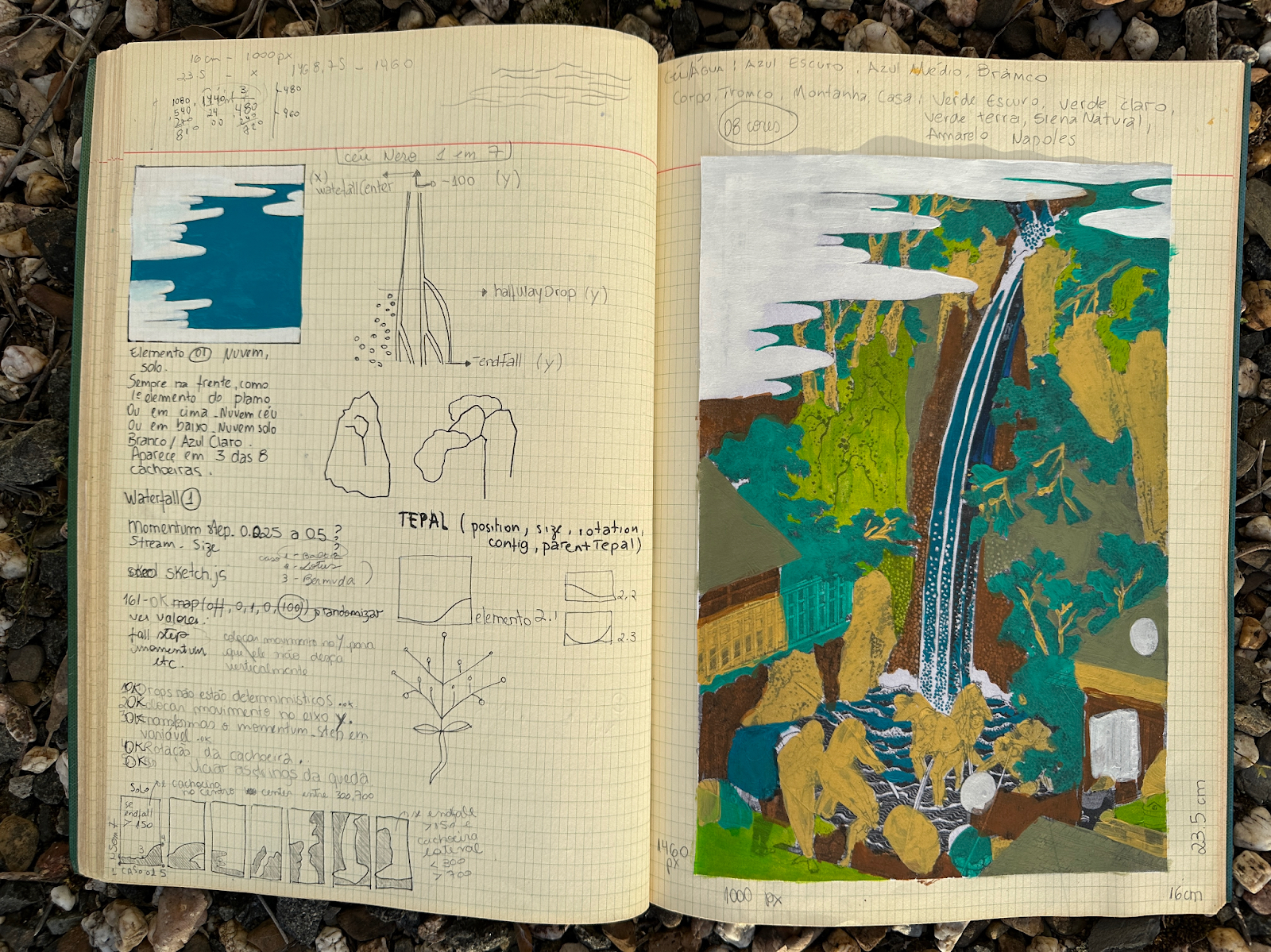

I first looked at Katsushika Hokusai’s series A Tour of Japanese Waterfalls, circa 1832–34, in LACMA's collection. I was 17 years old when I first saw Hokusai's work in 1999 at the exhibition Ukiyo-e: Japanese Engravings, exhibited at Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo. Since then I have been interested in the schematization of natural elements in the tenuous limit between abstraction and figuration and the use of patterns by ukiyo-e.

For the generative piece I created for the museum in response to Hokusai, which I call A Tour of Hypothetical Waterfalls, I isolated Hokusai's primary compositional elements and sought to understand their interactions—the water, earth, vegetation, and air. I abstracted Hokusai's human figures, translating them into rocks, since Hokusai used the same color palette for both. These elements presented exciting possibilities for the generative process. Also, printmaking was always about the idea of the multiple, which has a long tradition before NFTs of trying to create similar editions using a matrix. With generative art, this process goes further, with different multiples using a single matrix, the code.

You have also been looking at three different herbal manuscripts in LACMA’s collection, dating from the 13–17th centuries, from Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Can you tell us a bit more about the work you are creating in response, which you call Pages from an Artificial Plant Script?

I have always been drawn to organic natural forms, plants, and flowers, so when I discovered this beautiful herbal manuscript in the museum, I wanted to see how I could translate their logic into my practice. The process has been exciting and resulted in an artistic breakthrough or the opening of a new door, which presents many possibilities I am actively exploring. As I began working with these herbal manuscripts, I turned to Johan Gielis equation, the Superformula, which I first encountered in 2020. I was fascinated by the possibility of his Superformula, which makes possible the generating shapes that recall the universe of flowers and other botanical elements. In 2020, I started researching how to incorporate this into my creative process. Still, it wasn't until 2022, with the release of the Underwater series, that the exploration began.

In 2023, with the invitation to create a work inspired by the LACMA's collection , my idea was to look at these early herbal manuscripts in the museum and create a new Herbal Manuscript filled with artificially generated flowers using the Superformula. The most significant difficulty was not implementing the equation, which has several online versions and examples, but instead coding parameters to generate flower-like patterns.

Unlike many equations, the parameters I used are not intuitive, and simply testing random numbers got me nowhere. Still, the desire to create a compendium of artificial flowers using the supershape results did not leave my mind.

It was necessary to develop a method to generate hundreds of thousands of shapes and select those that resemble a flower.

Rodjun was responsible for coding our interactive tool, and the software developed worked as the vessel for our explorations through the Superformula universe. We've envisioned a versatile tool to deliver both interface and data generation. Based on Primo Brandi and Anna Salvadori’s scientific paper "A Magic Formula of Nature," which describes an equation that allows one to expand upon Gielis's work, Rodjun adapted results to Javascript (using the p5.js library for the graphics generation). Although there were great existing open-source projects that reproduced the graphic results of the Superformula (including an R package called biogeom, in which Johan Gielis himself was involved), we understood there were fascinating new possibilities in a solution that would also offer easy access to different kind of users, in a wide variety of platforms.

The combination of JavaScript and p5.js offers access to virtually any web browser. The development of this tool allowed us to propose new questions about the Superformula world: how would people relate to supershapes during an interactive and dynamic image generation process? What are the underlying (natural?) patterns found in the almost infinite space of supershapes?

In the context of the Gielis equation, the different combinations of its parameters, and their underlying patterns, still need to be explored. Thus, Vicente Gomes used supervised and unsupervised machine learning as tools to expand the classification of the universe of supershapes. In this sense, powerful algorithms and high-level computation allow machines to identify and categorize patterns previously absent to the human eye. For the first method, supervised learning, a small batch of generated supershapes was manually characterized and curated, serving as the training dataset for the model. After the initial classification, we focused on shapes that were classified as flowers. Our idea here was to identify species and their closest relatives; we used an unsupervised clustering method. Here, we found the shapes and the forms that originated the flowers presented in the Pages from an Artificial Plant Script.

The first description of a species should also take the essential information to generate its form. Thus, Crucis orbitalis is the first species created and cataloged in this universe that will be continuously expanded. My hope is that the Plant Script project can be printed as a contemporary herbal book.

I am honored and excited to have the chance to develop these works in dialogue with LACMA’s collection. I am certain that looking at the past in order to create the future has always been one of the most amazing human practices.

It is exciting to see how this project has opened up new conceptual doors for your practice, Monica. I love the idea of a book based on the dialogue you have been developing with the museum and your algorithmic creations. We are all looking forward to you sharing this work with the world soon!