Korean Treasures from the Chester and Cameron Chang Collection, opening at LACMA later this month, features Korean artworks recently gifted to the museum by Dr. Chester Chang and his son Dr. Cameron C. Chang. This gift joins the museum’s existing Chang collection of over 50 Korean works generously donated by the family between 2003 and 2007. Included are a number of paintings and calligraphic works, many traditionally mounted as hanging scrolls and panel screens. Currently at LACMA’s Conservation Center, specialists in paper conservation are actively involved in caring for these newly acquired paintings and preparing for their safe display in the Resnick Pavilion.

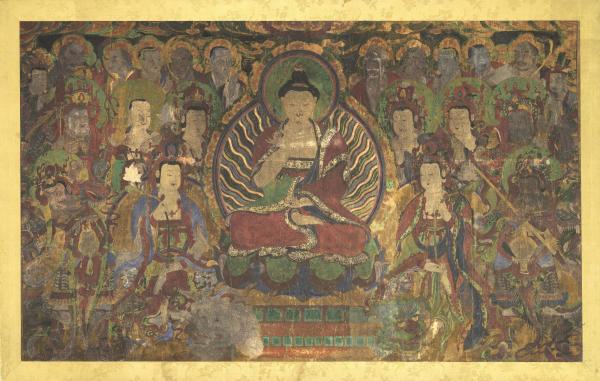

Among the treasures going on view is a large Buddhist painting from the 18th century, made during Korea’s Joseon dynasty (1392–1910). It depicts a scene of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, known in Korea as Seokgamoni, seated on a lotus throne, surrounded by deities, guardians, and disciples. Done in bold mineral colors on a very fine silk ground, the painting has indications of gold on various objects carried and worn by Buddha’s entourage. In the detail below, one of the Heavenly Kings, Damun-cheonwang, stands out with a crown on his head and a pagoda and parasol in hand—all rendered in once-brilliant gold. Despite having worn away over time, these metallic traces reveal that the painting would have originally looked very different, with luminous and reflective features meant to heighten the symbolic significance and sacred presence of the work.

A painting like this might have originally been displayed as a hanging scroll or wall painting in a Korean temple altar. At some point, it was mounted onto a Japanese-style screen with silk brocades bordering the front. Upon acquisition by LACMA, the painting, while well supported by this structure, had been punctured. This resulted in a right-angled tear near the bodhisattva Manjushri (Munsu) on Buddha’s right. In its damaged state, the painting needed some remedial attention before it could be displayed in the galleries.

The painting’s puncture was fortunately not detrimental to its overall stability. However, recognizing the potential for the damage to worsen if left untreated, we proceeded with a plan to repair the torn section. Such repairs are typically performed from the backside of a work, but for a screen painting, this proved to be a slightly more difficult task.

Paintings mounted as screens present a special challenge for conservation due to their complex construction over a hollow framework. The screen itself is made of a wooden lattice panel covered by many layers of thin paper on each side. This underlying structure means that the back of a painting cannot be easily accessed for treatment unless it is completely removed from its mount. This process, known as remounting, is highly specialized and interventive, and requires the expertise of a professional trained in the conservation and mounting of Asian paintings. For these reasons, not all paintings warrant intensive treatment, especially if the existing mount is stable and the damage is within a manageable state of preservation.

In the case of the Seokgamoni painting, we deemed minor remedial treatment would be suitable for stabilizing the puncture. The only question that remained was how we would go about reaching the back of the painting for the repair. After some deliberation, we chose an alternative and somewhat creative approach.

In our initial assessment of the painting, we determined that the torn area around the puncture could be lifted, creating a slight opening through which we inserted a piece of sturdy, long-fibered paper fitted with thin thread extensions. Once pasted and positioned beneath the puncture, we used the threads, like strings on a puppet, to draw the paper into contact with the back of the painting. As the paste dried, we realigned the tear and applied even pressure on both sides of the repair. This proved to be a balancing act between maintaining the tension of the threads while gently pressing down on the painting to counterbalance the pull and encourage a flat, secure repair.

On the following day, we trimmed back the threads and were pleased to find that the puncture was strongly supported from beneath, and visually integrated with the surrounding painting.

With the puncture stabilized, we took the opportunity to do a bit of inpainting. As can be expected for a work of its age, the surface of the painting had become worn over the centuries. However, our attention was drawn to a few small losses that reached the outermost paper layer of the screen. These visibly “white” losses significantly stood out against the darker ground of the painting. To lessen their visual impact, we applied conservation-grade watercolor paints, in small, controlled amounts, using a fine tipped brush and as little water as possible. Importantly, the paint was applied only to the exposed screen paper, not to the painting itself. This means that our cosmetic touch ups can be removed should that become desirable in the future.

The purpose of this treatment was to bring the painting to a condition suitable and stable for display using remedial techniques. In the future, a more comprehensive treatment, carried out by a professional mounter, may be necessary to further stabilize the painting’s surface and place it in a more culturally appropriate Korean-style mount. For now, the remedial actions taken by the paper conservation team have played an important role in both extending the painting’s preservation and ensuring its safe display throughout the duration of the exhibition. The next time you come to LACMA, be sure to pay a visit to Seokgamoni-bul and his entourage in Korean Treasures, on view in the Resnick Pavilion from February 25 through June 30, 2024.