As LACMA prepares for the 2026 public opening of the new David Geffen Galleries, the future home of the museum’s permanent collection spanning a breadth of eras and cultures, we’re sharing 50 iconic artworks that will be on view in the building over the next 50 weeks in the series 50 Works 50 Weeks.

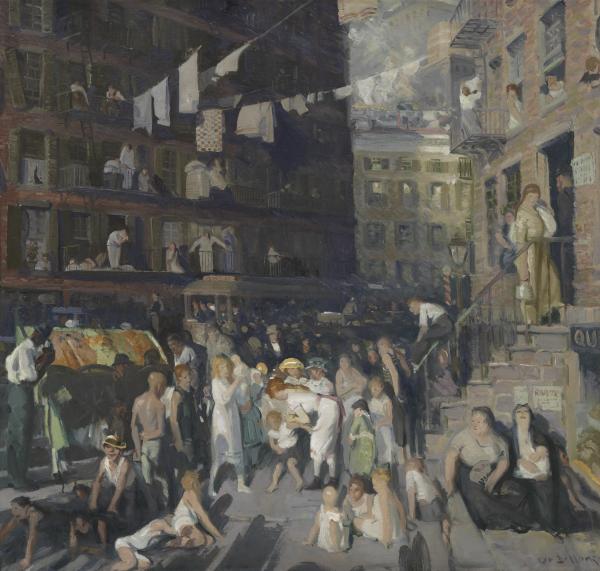

George Bellows’s Cliff Dwellers (1913) was among the museum’s first acquisitions, made before LACMA was LACMA in the summer of 1916, when our collection was still part of the Los Angeles County Museum of Science, History, and Art. It presents a slice of life outside a tenement on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which, like Los Angeles, was experiencing a population boom. When looking at Bellow’s composition, one is struck by the energy and buzz that radiates from the canvas. Although Bellows and many of his fellow Ashcan School painters lived comfortable middle-class lives, their works often depict working class life and labor, at times confronting the apathy felt by the urban elite towards those with lesser means.

The spirit of the scene is conveyed primarily through individual figures going about their day, converging in a tableau of dynamic movement. Bellows calls attention to the overlooked and often monotonous activities that make a city. On the right side of the canvas a mother ascends the stairs, while children huddle playfully in a circle in the foreground and adults take a break from the heat, hang laundry out their windows, and enjoy the breeze that gently rustles the clothing lines. With the vibrancy in this painting also comes a sense of fatigue, as the heat settles thick and heavy on people who could not afford to leave the city for the summer.

The artist abides by and plays with a distinct color and compositional theory created by artist Hardesty G. Maratta, using mainly complementary colors like a musician would use chords. Within Maratta's theoretical framework is a focus on geometrical forms. A pattern of pinholes was found in this painting where it appears Bellows pierced the canvas to create horizontal, vertical, and diagonal rows. The pins are placed so that they form equilateral triangles, the key concept of the Maratta system. An example of this is the figure of a woman holding a fan in the lower right corner, who has a pinhole at the top of her head and at the point of each elbow.

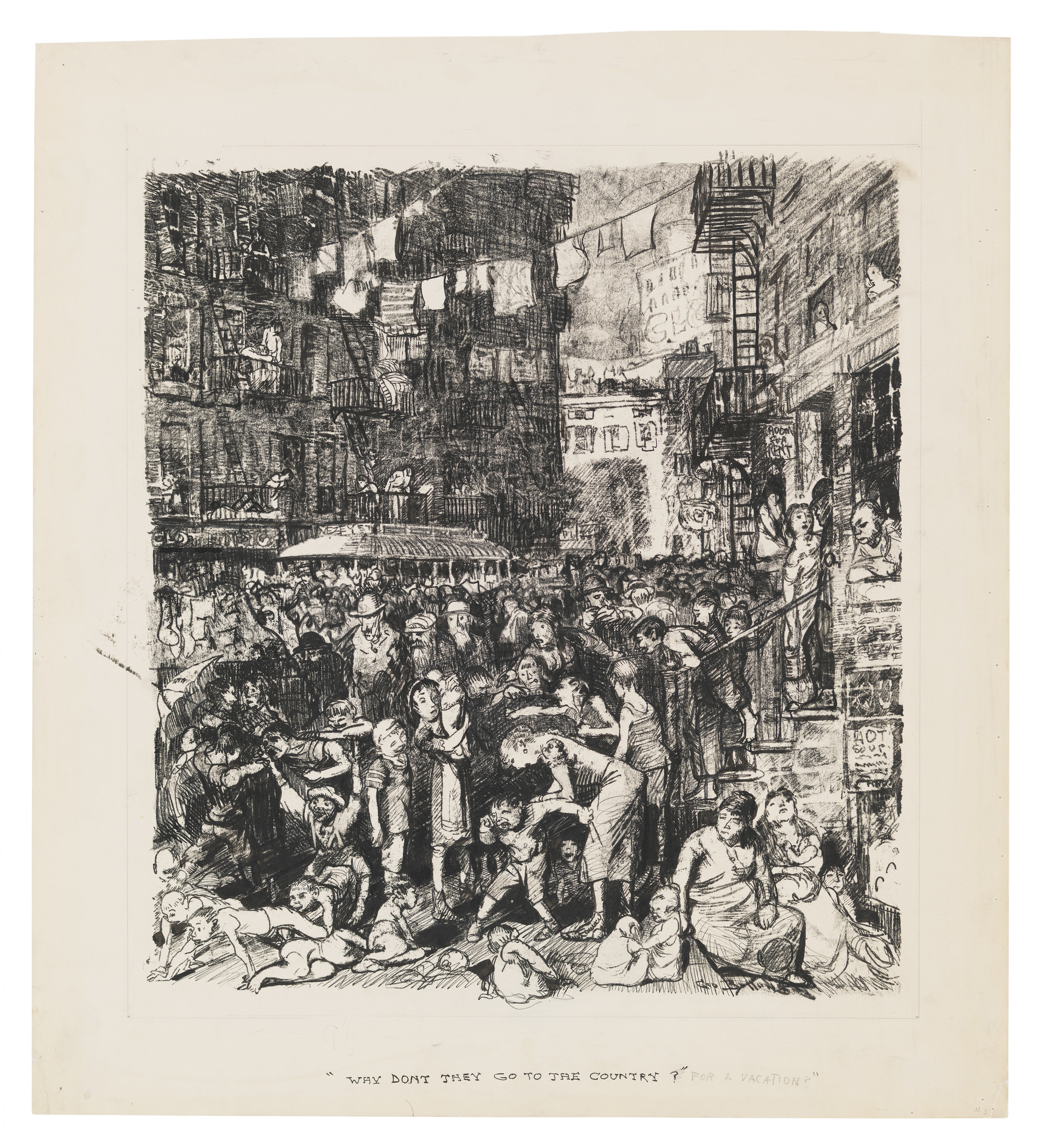

As the United States transitioned into a modern industrialized society, artistic representation began to shift as well. While Impressionism and Post-Impressionism still maintained popularity, an interest in realism grew in literature and the fine arts, revealing changes in social and economic dynamics. While Bellows rendered the crowded streets with pleasant colors and a clean, pure light, a slightly different, transfer lithograph of this composition was also made by the artist. Why Don’t They Go to The Country For Vacation? (1913) is a darker, grittier depiction of urban poverty, the title of which mocks the wealthy who failed to understand why the working classes could not escape to the country during the hot, overcrowded summer months. Although Bellows’s painting would have been viewed mainly by elite art patrons in a gallery setting, the lithograph was printed widely and was featured as the frontispiece for the August 1913 issue of the socialist journal The Masses.