As LACMA prepares for the 2026 public opening of the new David Geffen Galleries, the future home of the museum’s permanent collection spanning a breadth of eras and cultures, we’re sharing 50 iconic artworks that will be on view in the building over the next 50 weeks in the series 50 Works 50 Weeks.

On November 25, 1948, French artist Henri Cartier-Bresson received a telegram from Magnum, the photographic cooperative he cofounded in 1947, asking him to go to China to work on a story for Life magazine titled “The Last Time We Saw Peiping.” He arrived in Beijing just as the Kuomintang was falling and stayed for 12 days until the People’s Liberation Army forced him to move on. For 10 months, between December 1, 1948, and September 23, 1949, he documented the departure of Nationalist forces and the establishment of communism throughout China, shooting nearly 900 photographs that were published in a total of 5 articles in Life magazine and 35 articles in publications throughout Europe including Illustrated and Regards. He returned a decade later, in 1958, and stayed for four months between June 16 and October 23. This trip was meticulously arranged by his Chinese hosts and yielded 376 rolls of film. The photographs from both trips have been compiled into 4 books, including: From One China to Another (1956), China: As Photographed by Henri Cartier-Bresson (1964), and Henri Cartier-Bresson: China 1948–1949, 1958 (2019).

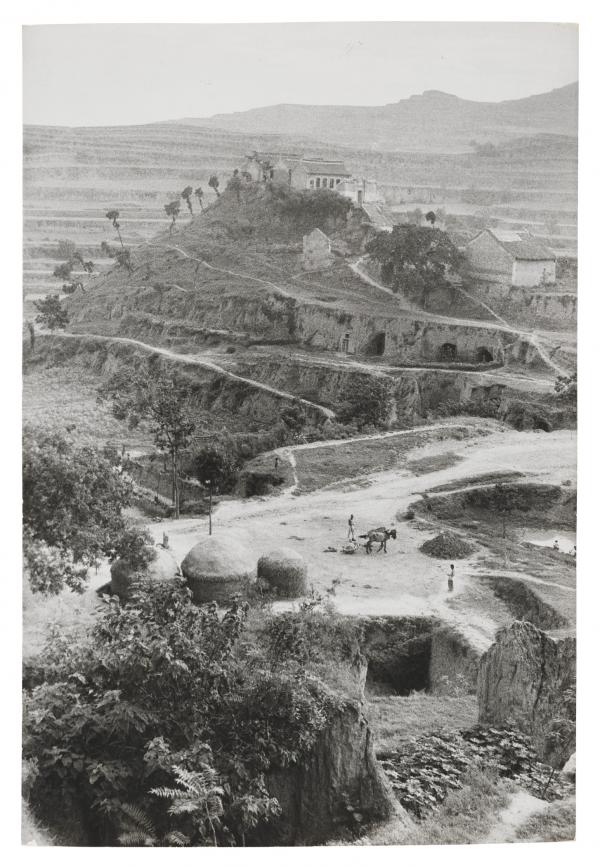

The directive from Life was to concentrate on scenes that revealed the “Chinese culture and character, the human angle of the city.” He took handwritten notes about each roll of film, which he often turned into captions. This image was made near Sanmenxia along the Yellow River, which is the site of the Sanmenxia Dam—a concrete gravity dam built for flood control as well as irrigation and hydroelectric power beginning in 1957 and completed in 1960; this is the time that Cartier-Bresson was photographing this region.

Cartier-Bresson is known for coining the term “the decisive moment” when the precise organization of forms and the significance of an event come together in a fraction of a second and are recorded photographically. The photographs made in China at this time reveal Cartier-Bresson’s efforts to capture the interconnected worlds of cultural events, political figures, Maoist propaganda campaigns, ordinary people, and landscapes. His work in China during this turbulent time was critical for his career and established him as a pioneer of photojournalism.