As LACMA prepares for the 2026 public opening of the new David Geffen Galleries, the future home of the museum’s permanent collection spanning a breadth of eras and cultures, we’re sharing 50 iconic artworks that will be on view in the building over the next 50 weeks in the series 50 Works 50 Weeks. A version of this post was originally published in 2009.

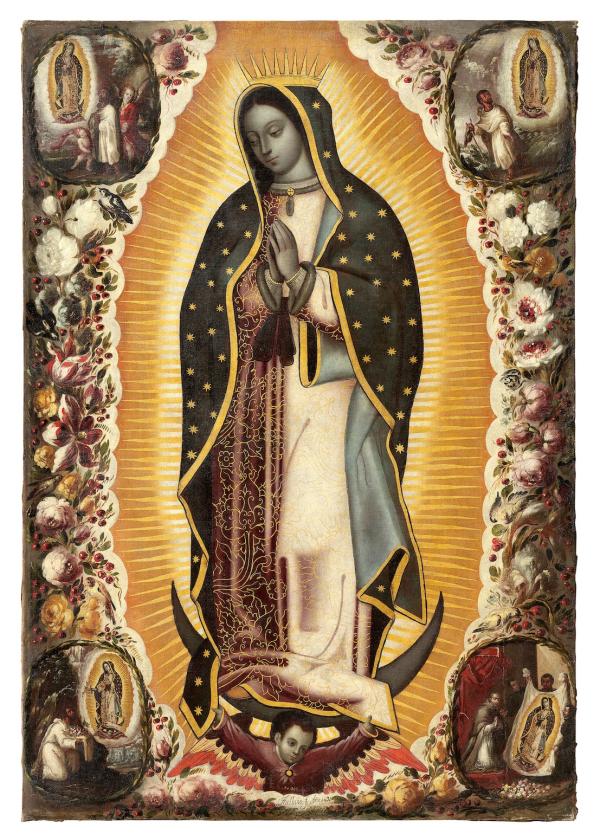

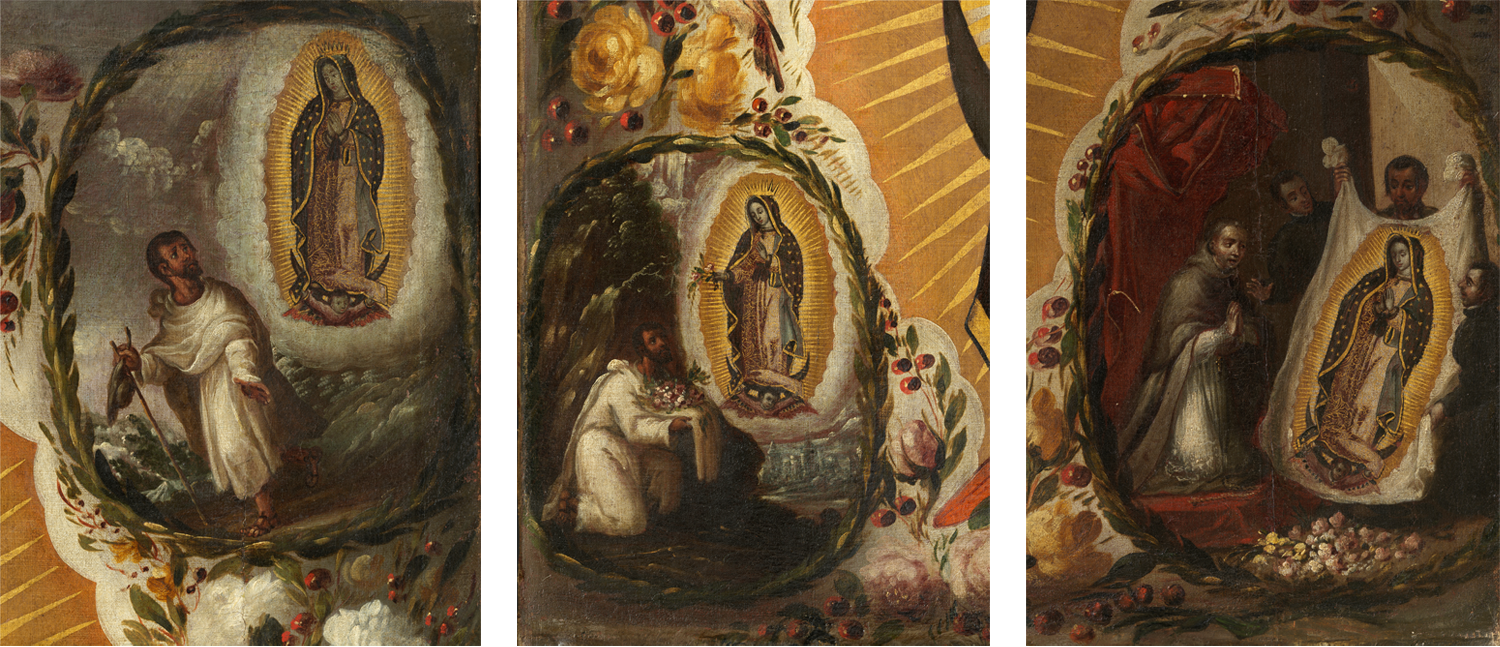

Our Lady of Guadalupe is one of the most reproduced images in the Christian world. This painting by Antonio de Arellano (1638−1714) and his son Manuel de Arellano (1662−1722) depicts the Virgin surrounded by four vignettes that narrate her miraculous apparitions. According to tradition, in 1531 the Virgin appeared several times to the Indigenous commoner Juan Diego, asking him to visit Bishop Juan de Zumárraga (r. 1528−47) so he could build her a chapel at the hill of Tepeyac, north of Mexico City. At first, the bishop refused to believe Juan Diego, who then unfolded his cloak filled with the rare flowers that the Virgin had sent as proof, revealing her miraculously imprinted image. In awe, the bishop fell to his knees and begged the Virgin for forgiveness. Legend has it that the image on Juan Diego’s cloak is the one venerated today at the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City, which continues to attract millions of pilgrims each year.

Ever since I started building our collection of Spanish American art at LACMA, acquiring a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe was one of my priorities. I waited for many years for just the right one. When I found this painting in 2009 signed and dated Arellano F[ecit] 1691, I was thrilled. (The surname refers to Antonio and Manuel de Arellano, members of one of the most important families of artists in 17th-century Mexico, who often collaborated.) A few days later, after the painting arrived at LACMA, I was able to decode a faintly rendered inscription on the lower edge: tocada a la original (“touched to the original”).

This made the acquisition doubly exciting, as it suggested that the Arellanos based their depiction on the original image of the Virgin venerated at the Basilica de Guadalupe. To meet increasing demand for reputable copies of the Virgin’s titular image, the Mexican artist Juan Correa (c. 1645–1716) produced a waxed-paper template after the original icon that enabled painters to accurately reproduce the design. This accounts for the similar dimensions of some paintings despite variations of style and details.

Images that were closer to the original were believed to be more miraculous and therefore were more valued. The painting must have been commissioned by someone in need of a miracle-making image. That this large canvas of Guadalupe made its way to LACMA more than three centuries after it was painted is just short of being a small miracle itself.

Selected Readings

David A. Brading, Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe; Image and Tradition across Five Centuries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Mirta Asunción Insaurralde Caballero, “La pintura a inicio del siglo XVIII novohispano: Estudio formal, tecnológico y documental de un grupo de obras y artífices; Los Arellano” (PhD diss., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2018).

Ilona Katzew, ed. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: DelMonico Books/D.A.P., 2022).

Paula Mues Orts, “‘Que no hay quien pueda copiarla’: la virgen de Guadalupe de México y de cómo los pintores novohispanos intentaron retratarla,” in Tan lejos, tan cerca, Guadalupe de México en España, exh. cat. (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2025), 141–201.

Jeanette Favrot Peterson, Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

Stafford Poole, Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1996).

William B. Taylor, “The Virgin of Guadalupe in New Spain: An Inquiry into the Social History of Marian Devotion,” American Ethnologist 14, no. 1 (1987): 9–33.