LACMA has recently received a landmark gift of 90 works by Ardeshir Mohassess, significantly expanding the museum’s modern and contemporary Iranian art collection and positioning LACMA as the leading international repository of the artist’s work. Created between the 1950s and the 1990s, these drawings and watercolors span transformative decades in Iran, observed by Mohassess first from within the country and later from the diaspora. They document the final years of the Pahlavi regime (1925–1979), critique its rushed modernization and expanding bureaucracy, and ultimately bear witness to the authoritarian forces surrounding the 1979 Revolution and the repressive years that followed under the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Born in Rasht in 1938 and trained in political science and law at Tehran University, Mohassess became modern Iran’s most influential social satirist. A self-taught artist, he produced remarkably precocious drawings from a young age; his first works were published while he was still a teenager in Towfiq, Iran’s leading satirical and literary journal. His practice intersected with popular culture—including Hollywood films—as well as royal imagery associated with the Qajar dynasty (1789–1925), predecessors of the Pahlavis. Calling himself “just a reporter,” Mohassess believed that “a simple line is the mother of images, capable of soaring, cursing, mourning, and wounding.” His razor-sharp black linework and fearless critiques of both the monarchy and the clergy—some published in Kayhan, one of Iran’s most influential daily newspapers—led to increasing censorship and police harassment, prompting his departure from Iran in 1976. After relocating to New York’s Greenwich Village, where he lived in self-imposed exile until his death in 2008, his work reached international audiences through The New York Times, The Nation, and other major publications.

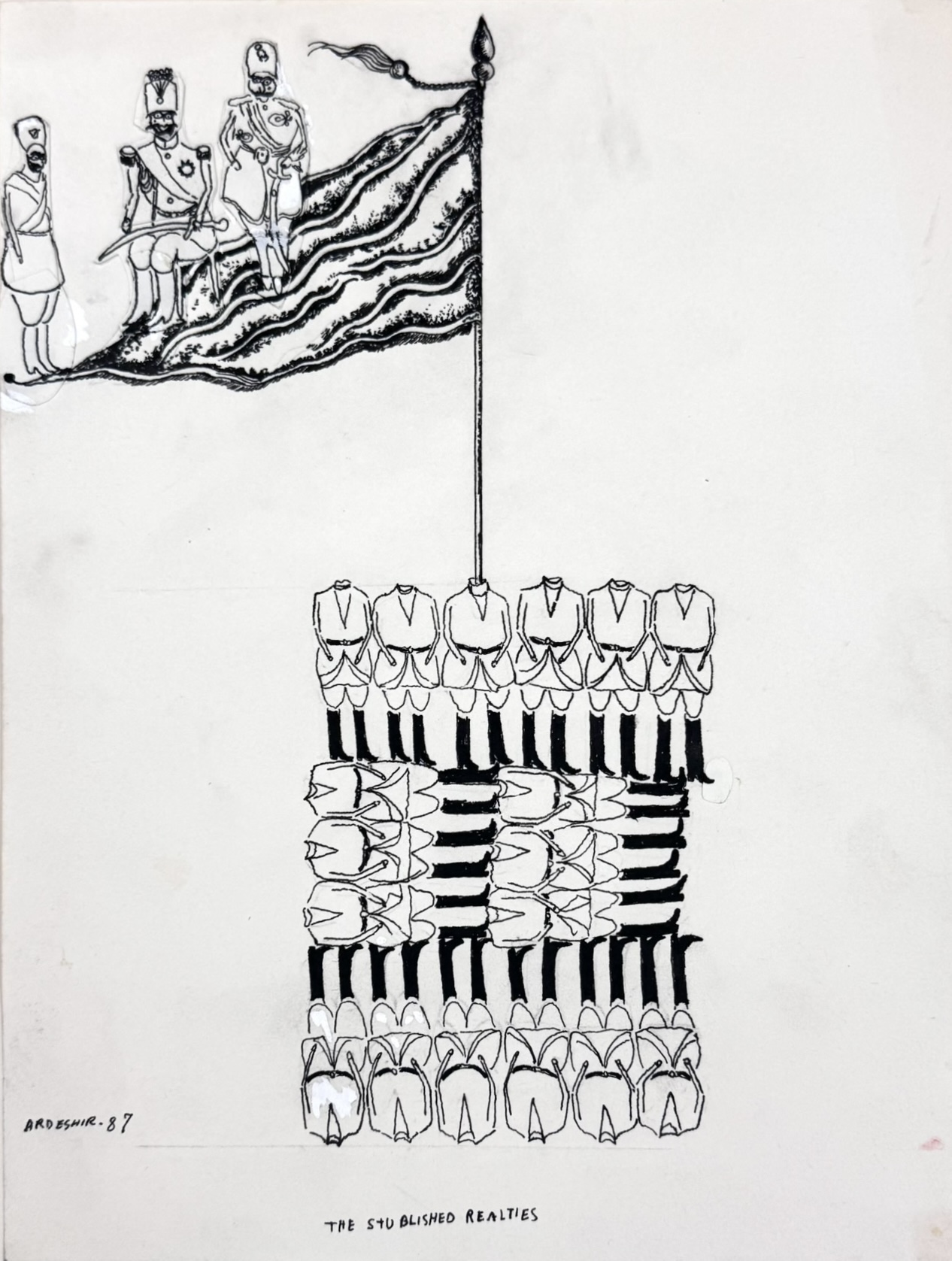

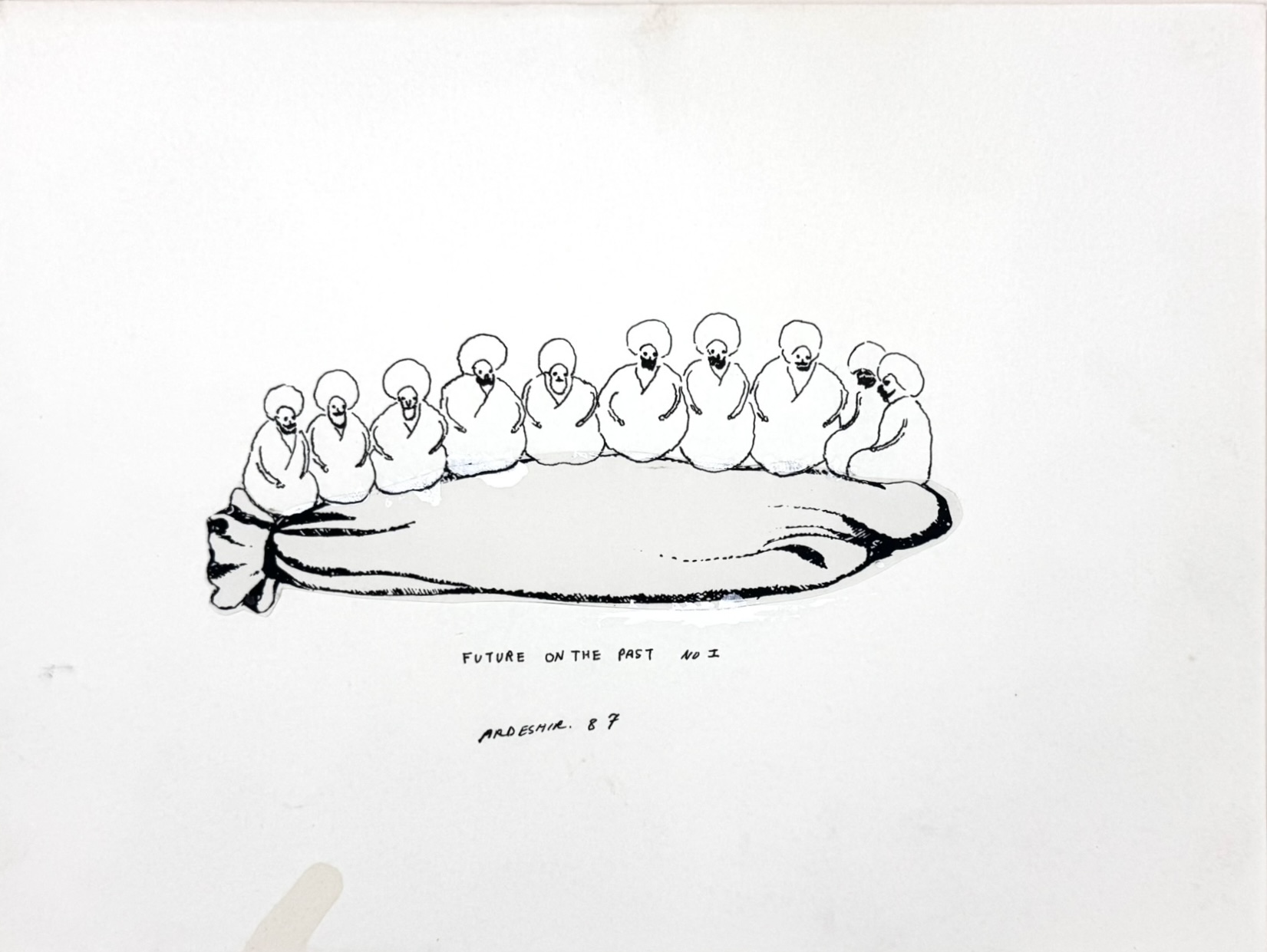

In New York, and even after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Mohassess continued to depict the shah and his entourage with unrelenting scorn, disguising them as their Qajar predecessors, while also maintaining his biting representations of the newly empowered clerical class. These black-ink drawings are characterized by simple, briskly drawn outlines and a detached tone that frequently reveals the artist’s fascination with the macabre, including headless corpses and severed limbs. Although produced primarily in the 1970s and 1980s, the works retain a striking immediacy and relevance. Drawings such as Future on the Past No. 1, which portrays a group of mullahs seated around a shrouded, body-bag-like corpse, are both prescient and tragically applicable to ongoing events in Iran. Mohassess thus shares a sensibility with a younger generation of Iranian artists represented in LACMA’s collection, whose work over the past decade and more has continued to resonate with increasing urgency (see Barbad Golshiri’s The Untitled Tomb). What emerges from these works is not a declaration, but a record. They assert art’s role as witness: a means of documenting what power seeks to obscure and of preserving memory when official histories fail.

This group of works represents the first of two—or possibly three—additional tranches to be donated by Dr. Ardeshir Babaknia, an Orange County–based physician who holds the largest known collection of Mohassess’s work. Most of these works were given to him directly by the artist as tokens of friendship and gratitude; Mohassess lived with Dr. Babaknia while undergoing treatment for Parkinson’s disease. This extraordinary gift will provide essential material for future exhibitions. Moreover, LACMA’s goal, shared by Dr. Babaknia, is to establish the museum as a key resource and study center for Mohassess’s work—creating the premier platform for research and for preserving the artist’s legacy.