One of the aims of the curators organizing The Written Image exhibition now in the Ahmanson’s Rifkind Gallery was to highlight some of the lesser-known figures of the Expressionist period whose graphic images were as groundbreaking and as vibrant as those made by the more famous artists associated with the movement. Along with stellar examples of prints and illustrations by the likes of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Kaethe Kollwitz, and Wassily Kandinsky, the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies also houses thousands of illustrated books and portfolios created by graphic artists whose names are virtually unknown today but whose contributions to art demonstrate the breadth of aesthetic experimentation in Germany in the years immediately following World War I.

A particularly exciting discovery for us was the production of “wordless novels” by two of these forgotten artists. Their innovative imagery appeared in formats that have special resonance today, for they can be considered prototypes of the currently popular graphic novel. One of the earliest of these experiments displayed in the exhibition was the Viennese artist Carry Hauser’s Buch der Träume (Book of Dreams). In 1921, Hauser was a member of the German artists’ society Der Fels (The Rock), a group that sought to spread the Expressionist aesthetic more widely through the production of print portfolios. Under the auspices of the society, Hauser published his portfolio of eight woodcuts in a very limited edition. The woodcuts begin and end with lettered title page and colophon, but the remaining images contain no captions. They can be read instead as a nearly surrealistic narrative sequence. They portray Hauser’s own dreams, rife with erotic fantasies, feelings of anxiety and a fear of falling; they create a somnambulant mood rather than a plotted story. The copy in the exhibition, with its bright blue cover, is a facsimile reprint produced by Munich’s Galerie Pabst in 1976 and signed on each print by the artist. Hauser went on to a career as a painter in Austria, with little subsequent work in printmaking. His Buch der Traüme remains as a reminder of his youthful affiliation with the Expressionist groups who saw in graphic art the most expeditious method of conveying visually their autobiographically emotional ideas.

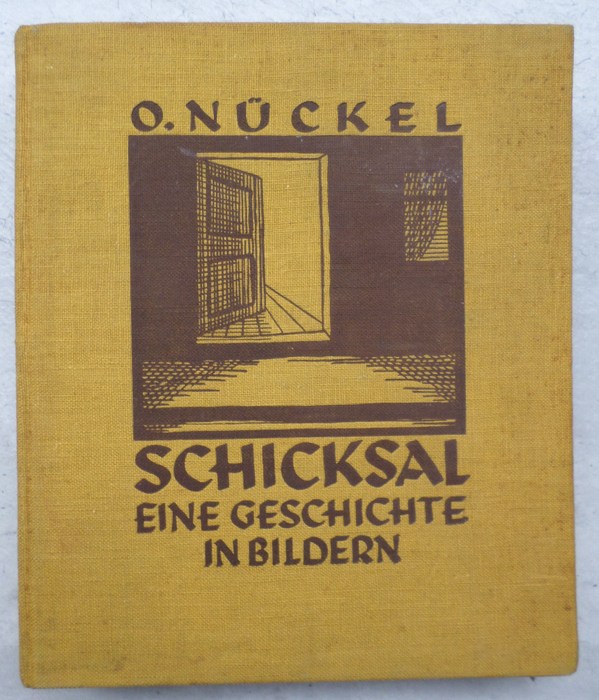

An even more astonishing “wordless novel” found in the Rifkind Center’s rare books collection is Otto Nückel’s Schicksal (1926). Praised by one critic as “one of the most innovative creations of German printmaking and illustration of the Weimar era,” Nückel’s ambitious production presents a searingly original story without text. Unlike Hauser, for whom print portfolios represented only a small portion of his artistic output, most of Nückel’s career, beginning in 1914, centered on book illustration and graphic cartoons. Schicksal was his masterpiece.

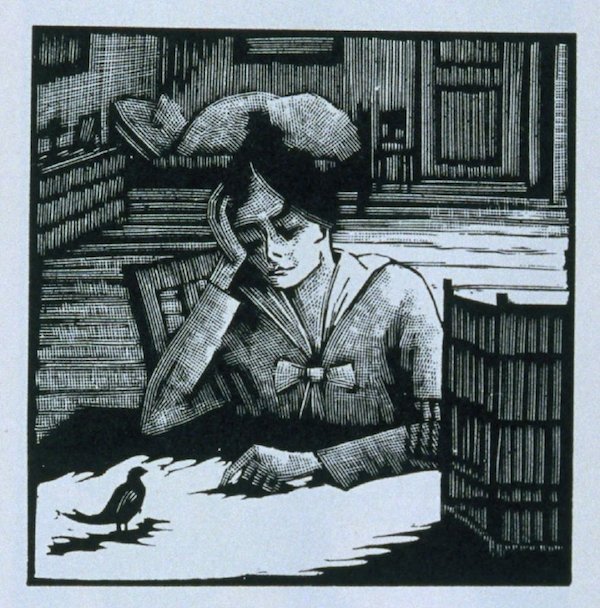

Like his better-known contemporary, the Flemish master of the wordless novel Frans Masereel, Nückel worked initially in woodcut. (Masereel’s Book of Hours [1926] is also on display in this exhibition.) But in the 1920s, he made a radical change in his practice when he discovered the aesthetic possibilities of Bleischnitt, a form of lead engraving used primarily in commercial printing and ornamentation. This process allowed Nückel to achieve in his images subtler gray tones and a finer differentiation of form than the stark contrasts of black and white characteristic in the Expressionists’ woodcuts. In seventeen short chapters with lettered title pages, Nückel depicts in Schicksal an irredeemably bleak narrative of a poor woman’s life journey. In 189 complex images, the grim story unfolds as the heroine suffers illegitimate birth, murder, prostitution, and ultimately a violent death. The book was Nückel’s only foray into the genre of pictorial narratives, and no other German artist ever achieved anything comparable to his Schicksal.

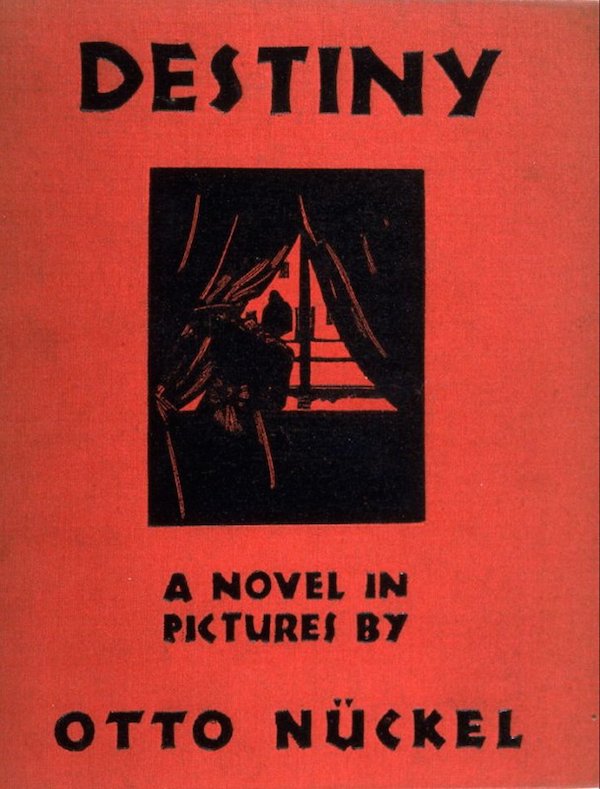

Perhaps as a result of the artist’s mastery of the lead-engraving technique, Nückel came to the attention of the American woodcut artist Lynd Ward, who was also producing wordless novels in the late 1920s and 1930s. In 1930, the American edition of Schicksal was published as Destiny: A Novel in Pictures by Farrar & Rinehart, with English chapter titles provided by the artist. This edition is still in print, and has served as inspiration for many American graphic novelists since it first appeared. In Germany, Nückel increasingly retreated to the more benign subjects of cartoons and humorous illustrations for magazines; when he died in 1955, he was remembered primarily as a caricaturist, with little mention made of his pioneering work as a graphic novelist.

These books by forgotten artists of the 1920s, along with the other examples on display in The Written Image exhibition, represent only a fraction of the richly diverse resources available in the collections of the Rifkind Center. The Center is open by appointment to anyone who wants to research the art and artists of Germany during the years in which Expressionism came to the fore and led to such exciting new aesthetic directions.