At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) today, L.A.-based philanthropist and business leader A. Jerrold Perenchio announced his agreement to bequest the most significant works of his collection to LACMA’s planned new building for its permanent collection. The promised gift will dramatically transform the museum’s collection of 19th- and 20th-century European art. Consisting of at least 47 works including paintings, works on paper, and sculpture, the majority of the collection is focused on the 1870s through the 1930s—an era that gave rise to some of the most radical and inventive moments in the history of art.

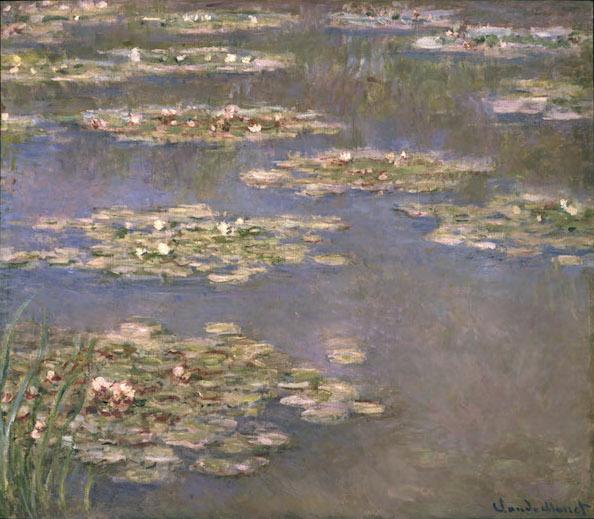

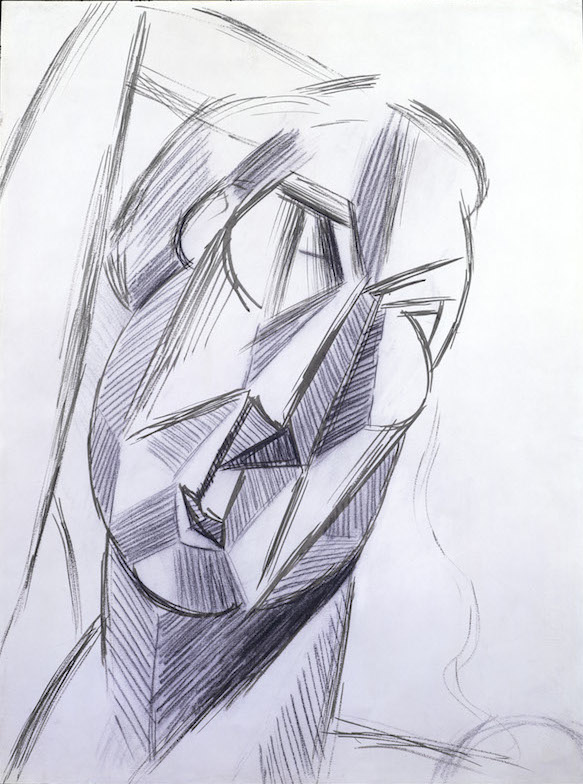

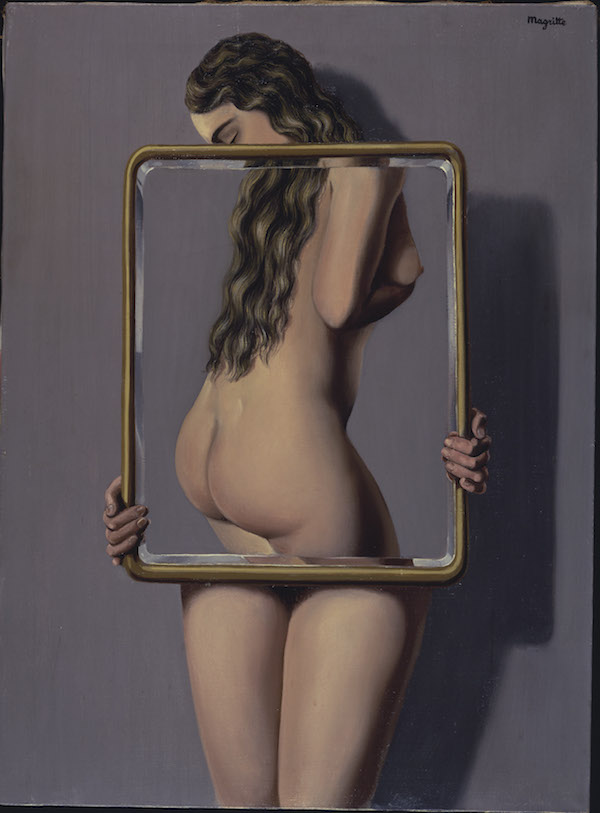

The distinguished collection, rarely seen in public, elucidates the road from Impressionism to Modernism. Highlights include three significant canvases by the great French Impressionist Claude Monet—a classic painting of water lilies, Nymphéas (c. 1905), the grand still-life, Asters (1880), as well as one of the four versions of the iconic Le Jardin de l’artist à Vétheuil (1881); the first painting by Edouard Manet to enter LACMA’s collection, the portrait of M. Gauthier-Lathuille fils (1879); Au Café Concert: La Chanson du Chien by Edgar Degas (1875); and three paintings by Camille Pissarro, among them the early Impressionist Le Déversoir de Pontoise (c. 1868). A Post-Impressionist standout by Pierre Bonnard, Après le repas (1925), joins a group of important 20th-century works, including Pablo Picasso’s early drawing Tête (Head of Fernande) (1909), two exceptional paintings by Fernand Léger, and two by René Magritte, including the exceptional Les Liaisons dangereuses (1935).

News of the historic gift follows on the heels of a unanimous vote by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors yesterday to support LACMA’s plans for a new museum building designed by Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, through a plan to contribute $125 million and future financing, to be matched by $475 million in private support. The new building, which will replace four of the museum’s seven current buildings, is intended to present LACMA’s vast and wide-ranging permanent collection, as well as conservation and study facilities.

Mr. Perenchio said, “LACMA has made tremendous progress over the past seven years under Michael Govan’s leadership, along with the support of its Board of Trustees and the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors. With the newly proposed Peter Zumthor building poised to deliver LACMA through the 21st century and beyond, I decided now was the perfect time to announce that I intend to leave the most important part of my art collection to the museum. Hopefully, my gift will serve as a catalyst to encourage other collectors to do the same and also stimulate major private donations to ensure that the Peter Zumthor building is built in a timely manner.”

“Gifts of this magnitude are incredibly rare, especially in the fields of Impressionist and Modern art,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “2015 will be LACMA’s 50th anniversary, and it is simply astounding to see how far this museum has come in just a few decades. Mr. Perenchio’s generous gift is a cornerstone of our future. Without this collection LACMA could not tell the story of Impressionism and the birth of Modern art. Mr. Perenchio’s artworks will become some of this museum’s greatest highlights.”

“We are excited for the transformative effect a new building by Peter Zumthor will have on Los Angeles,” said County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky, “but what is most important is the art inside the building, available to all Angelenos and attracting cultural tourists from near and far to LACMA. Our hope is that the County’s contribution to LACMA’s future, paired with Mr. Perenchio’s historic gift of art, will spur others in the community to support LACMA’s future.”

The Perenchio collection is the latest in a series of significant art acquisitions in the last seven years. Since 2007 LACMA has added more than 19,000 objects to its collection of over 120,000 works from ancient times to the present. This includes the Janice and Henri Lazarof collection of Modern art, the Marjorie and Leonard Vernon collection of photography, made possible by a gift from Wallis Annenberg, collections of European fashion, ancient American art, and art from the Pacific Islands, as well as individual masterpieces by the likes of Thomas Eakins, Maruyama Ōkyo, Henri Matisse, and others.

Terry Semel and Andy Brandon-Gordon, Co-Chairs of LACMA’s Board of Trustees, added, “The Board of Trustees is overjoyed to accept this priceless collection of European masterpieces from one of L.A.’s most exceptional citizens. Now, we will honor Mr. Perenchio’s wishes and partner with L.A. County and complete the fundraising necessary to build the magnificent Zumthor addition to LACMA. “

“A museum’s heart and soul is the art that resides there,” said Lynda Resnick, LACMA Trustee and Chair of the museum’s Acquisitions Committee. “This amazing gift gives us a reason to rejoice as our 50th anniversary approaches next year. Mr. Perenchio is an Angeleno through and through, giving generously to causes that have moved our city and citizens forward, all of which have been given anonymously until now. Putting Mr. Perenchio’s name on this gift lets everyone know of his refined taste in amassing this stunning collection, and provides insight into the man behind the gift as well.”

Select works from Mr. Perenchio’s promised gift will be on view at LACMA in the spring of 2015, coinciding with the museum’s 50th anniversary.

Highlights of the Collection

A leading Los Angeles–based philanthropist and business leader, A. Jerrold Perenchio has been carefully acquiring a select group of masterpieces over the last three decades. The earliest work represented in the bequest is a study by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux for his multi-figured sculpture La Danse, from 1865, which was commissioned by the architect Charles Garnier for the new Opéra of Paris. The grand building pronounced a new, modern Paris, while embodying both the clarity and culmination of the styles that had preceded it. Carpeaux’s sculpture signifies the same: with its dynamic subject matter and its spirited figure, the sculpture marks the zenith of one era while signaling the beginning of the next, soon to be led by the French avant-garde. Among the twenty-two additional artists that follow Carpeaux in this collection, each contributes meaningfully to the narrative that moves along from his starting point—from the investigation of light and modern life in Impressionism, to the domestic interiors and emotional color examined under Post-Impressionism, through Cubism and experiments in Expressionism, to the Surrealism explored in the art before the Second World War, and finally to works made in the 1960s and ’70s by Jasper Johns and Marc Chagall.

While Edgar Degas experimented with nearly every type of media—painting and print, sculpture, and photography—at the core of all of his work stands his incredible facility as a draftsman. He was an artist who considered his approach very different from the Impressionists, despite his inclusion in their exhibitions and his shared commitment to depicting contemporary life. “Strong and true” his work was called by a critic in 1876, and Au Café Concert: La Chanson du Chien epitomizes these qualities in a definitive image of modern urban life. In this, one of his earliest depictions of a café-concert, the well-loved singer, Thérésa, is caught open-mouthed performing a whimsical song that required her to impersonate a dog. Under the harsh artificial glow of gas lamps, whites, reds, and pinks are interspersed with mustard yellows, grays, and browns to delineate skin and costume. Degas’s sophisticated palette and technical experimentation are at their best here: the picture is formed from layers of gouache, essence, and pastel over a monotype, and the unique composition conveys a sense of intrusion and instantaneity. All of these qualities would be drawn upon later in Degas’s career, even in the quiet moments of a work such as Pendant le Repose (c. 1880), a beautiful pastel and chalk drawing dedicated to his friend Edmond Duranty and also part of this generous donation. The gift of these two mid-career drawings will fill a gap at the museum where Degas is currently represented by the magnificent early portrait of the Belleli Sisters (c. 1865) and the late Dancers (1898). Additionally, three bronzes, including a nude study of the famous Little Dancer, will be part of this gift.

It is his paintings of modern life that position Edouard Manet as the definitive artistic leader in the transition from Realism to Impressionism, and his vibrant portrait of Louis Gauthier-Lathuille is emblematic of this change. Manet turns to the subject of urban life in this portrait, capturing the well-dressed son of the proprietor of a local restaurant in that very Parisian setting. Surrounded by hints of the restaurant’s outdoor garden, where the sitter posed for one of Manet’s most significant oil paintings earlier that year (Chez Père Lathuille, 1879, Tournai), the pastel is exceptional in both the complexity and detail of the composition. A lattice of vibrant green and the hint of a potted plant define the space of the sitter, while separating him from the tree and figure seen in the mirror—or window—behind him, an ambiguity that Manet deploys on several occasions throughout his oeuvre. The three-quarter-height stance allows Manet to explore the sitter’s costume, with the wonderful poof of the kerchief and the sparkle of the gold pin indulging the artist’s commitment to fashion and handling of chalk. Manet’s pastels number near one hundred, and the majority are beautifully, however simply, rendered bust-height portraits of women. While his portraits of men tend to be more varied and lively, this example stands alone as his most highly developed in the medium.

During the better part of the 1870s Claude Monet experimented with the atmospheric landscapes that literally gave Impressionism its name, and after a period of turmoil, including the death of his wife, by the start of the following decade the artist was finally regaining some personal and professional stability. At that time he began work on Le Jardin de l’artist à Vétheuil, a spectacular Impressionist portrayal of the artist’s garden. Bursting with summer’s sunflowers and quivering with the effects of sunlight, the picture is one of four versions of the same scene (the others reside at the National Gallery of Art, Norton Simon Museum, and a private collection), perhaps a memoir made knowing this was the final summer he would stay in the small rented house. Monet’s emphasis on the texture of paint coupled with the compression of space in the picture—there was a road between the staircase and the house that is completely missing here—was made increasingly evident as his career progressed. Indeed, plays between texture and surface are developed even further in the beautiful Nymphéas (c. 1905), one of his earliest paintings of water lilies. The tangibility of the pinks and greens that allow the lilies to literally float on the surface of the smooth blue-green water are a step on the way to the complete dissolution of spatial depth in the later paintings of the same subject. The magnificent still-life of Asters (1880) also exhibits the beginning of Monet’s interest in these spatial games, and all three paintings are part of this generous donation.

Dominating nearly three-quarters of the twentieth century, Pablo Picasso’s artistic output covers nearly every conceivable medium. Mr. Perenchio’s donation includes a painting of Marie Thérèse-Walter, along with six works on paper by this legendary artist, including the quiet but exquisite early drawing of his lover Fernande, who played a key role in Picasso’s development of both portraiture and Cubism. With an arm raised above her head, the subject immediately recalls the pose of the two central figures in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York), but the drawing exemplifies a critical step beyond this groundbreaking canvas: the subject is now reduced to a series of faceted planes that foretell the artist’s imminent innovations in Cubism. Quick, confident lines of gouache define the simplified features of eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, while the diagonal pencil strokes display the formal disintegration of the planes of her face. The tilt of her head suggests a hint of melancholy that will come to mark her visage as “Fernande,” even as all identifiable qualities melt away in Picasso’s continued use of her as Cubist model.

Drawing on the tenets of Cubism to develop a near-abstract style of painting around 1913, Fernand Léger continued to adapt the reductive aesthetic even after abandoning the pursuit of abstraction in favor of capturing subjects of contemporary life. This shift in focus took place after his exposure to the humbling technology of warfare while serving on the frontlines for France during World War I. In the period immediately following the war, during which mechanized versions of people and landscapes define his oeuvre (see Disks, 1918–19, LACMA), Léger turned his attention, as did many artists in the 1920s and ’30s, to the solidity of Greco-Roman classicism. This engagement brought a much-needed stability to many of the artists in the postwar period, and it is made manifest in Femme au bouquet. In this picture the quietly traditional presentation of a female figure holding flowers and a book is adapted for the modern world. The composition retains a tenderness despite the resoluteness of its mass, an apt reflection of the artist’s statement that “I had broken down the human body, so I set about putting it together again.” Etude pour La Lecture (1924), a single figure variant executed before the great La Lecture (1924, Centre Pompidou, Paris), and the later ceramic sculpture Les Femmes au perroquet (1952), also part of the promised gift, strikes the same balance of a constructed plastic humanity.

Pierre Bonnard was a founding member of the Post-Impressionist group Le Nabis, who focused on fusing the natural world with the symbolic vision of the artist, and whose imprint left an important mark on the future development of abstract art. The quiet, private nature of Bonnard’s paintings—intimate interiors, bathing scenes, portraits of family and close friends—is belied by their complex surface patterns and vibrant palette. This dazzling interior scene, which utilizes color to provide both structure and texture, exemplifies the artist’s efforts. The flattened figure of his wife and muse, Marthe, is distinguished from the geometry of the composition by a distinction in patterning and by her gentle arc over the table. The rigid symmetry of the table, its cloth pattern, and the alignment with the chair and cupboard behind it, coupled with her curved figure, have echoes of Cézanne and Matisse—the latter was a devoted admirer of Bonnard. The overall patterning is tapestry-like and recalls the paintings of his dear friend and fellow founder of Le Nabis, Edouard Vuillard, as exemplified in LACMA’s grand Walking in the Vineyard (1899). Vuillard’s delightful pastel of Sacha Guitry in His Dressing Room (1912), along with Bonnard’s glimmering seascape Bateaux Le Soir, Cannes (1924), will also join the museum’s collection.

Fundamental to the work of the Belgian Surrealist René Magritte is his play with pictorial reality, which is presented best in his most recognized image, La Trahison des images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (1929), already in LACMA’s collection. Joining it is another iconic example of Magritte’s illusionistic games, Les Liaisons dangereuses, from 1935. During the 1930s Magritte established his highly finished stylistic approach, secured his role as a leading Surrealist, and mastered the deadpan realism that made him a forerunner to Pop art. In this image of a nude woman, the ingenious visual arrangement simultaneously prevents and promotes sexual enticement. The incongruity of the flawless figure, however fastidiously rendered, reminds us of the construct of painting. This back and forth, found literally in the figure’s position and metaphorically in the real and imaginary nature of the image, lies at the heart of Magritte’s painting. This Surrealist duality can also be seen in the magnificent Stimulation Objective no. 3 (1939), where the rock, lion, and barrel, imposed with miniature versions of themselves in a beautifully painted landscape, pronounces the artist’s participatory role in the creation of painting as fiction. The addition of these two important paintings to the museum’s collection provides LACMA with the most significant grouping of the artist’s work on the West Coast.

About the Collector

Born in Fresno, California, in 1930, A. Jerrold Perenchio has lived in Los Angeles for nearly 70 years and is one of the most successful and respected businessmen and philanthropists in Southern California. After graduating from UCLA in 1954, Mr. Perenchio served in the U.S. Air Force for three years and earned his wings as a single-engine jet pilot. In 1958 he began his career in the entertainment industry as a talent agent for Music Corporation of America (MCA). Mr. Perenchio has always said he got his “MBA at MCA” over the course of his four years there. By 1963 he had started his own agency, Chartwell Artists, which grew to be the fifth-largest talent agency in the world and was eventually sold to International Creative Management. In 1973, Mr. Perenchio joined Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin at Tandem Productions, a television production and distribution company. Tandem was the most successful producer of prime time television at the time, with hit shows that included All in the Family, Sanford and Son, Maude, and many others. Mr. Perenchio and Yorkin produced the iconic dystopian science-fiction thriller Blade Runner (1982), directed by Ridley Scott and starring Harrison Ford, which has become a cult favorite. After the sale of Tandem to Coca-Cola in 1985, Mr. Perenchio went on to produce Driving Miss Daisy with the Zanuck Company (1989)—which won an Academy Award for Best Picture—and Frida (2002), starring Salma Hayek, which Mr. Perenchio produced with his wife. In 1977, Mr. Perenchio also cofounded National Subscription Television (ON-TV), one of the first over-the-air television subscription services. He also owned the Loews Theater Chain from 1985 to 1987 with locations in New York, New Jersey, Texas, and six other states. From 1992 to 2007 Mr. Perenchio was Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, and Controlling Shareholder, of Univision Communications Inc., turning the Spanish-language network into one of the most successful multimedia companies in the world. For the past thirty-five years most of Mr. Perenchio’s charitable donations have been made anonymously, with support given to the arts, education, health, and a wide range of organizations based in Los Angeles. Mr. Perenchio currently sits on the board of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation.