Larry Sultan: Here and Home is the first exhibition to present the full scope of the artist’s 35-year career. One of the most influential photographers of his generation, Larry Sultan (1946–2009) consistently challenged photographic conventions—from the conceptual playfulness of his early collaborations to the investigation of documentary strategies in his solo work. Raised in the San Fernando Valley, Sultan moved to Northern California in the early 1970s, but continued to draw inspiration from the architecture, atmosphere, and attitude of Southern California. Throughout the six major bodies of work included in this exhibition, themes of home and family resonate alongside Sultan’s interest in storytelling and the construction and presentation of identity.

Sultan’s career began in collaboration with his friend and fellow graduate student Mike Mandel, who he met in 1973 at the San Francisco Art Institute. They were both from Los Angeles and found themselves similarly at odds with the photography program’s traditional curriculum and San Francisco’s pervasive Beat culture. For 27 years, they collaborated on billboards, book projects, exhibitions, and other forms of conceptually based public artworks that tested traditional ideas about authorship and display strategies. By initiating conversations around appropriation and the influence of context on meaning, their work was instrumental in defining the role of photography in conceptual art of the 1970s.

Evidence was their breakthrough body of work (1975–77) and the one for which they are best known. Inspired by an encounter with NASA’s photographic records, Sultan and Mandel applied for an NEA grant to access similar archives at corporations, research institutions, and public agencies across the United States. The combination of government funding and official-looking letterhead of their own design convinced many to comply, including the Environmental Protection Agency, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, National Semiconductor, Northrop, Sunkist, and the General Atomic Company, among others. The result was a sequence of found images, made originally to document technological and industrial procedures and experiments. In their hands an uncertain narrative emerged that simultaneously confronted photography’s claim to objective reality, its status as art, and their roles as artists.

Sultan’s search for new photographic experiences beyond his conceptually oriented collaborations led to his series Swimmers (1978–82). Shot at public pools around San Francisco, the project was inspired by Red Cross swimming manuals, but these lush color images diverge substantially from his earlier works based on found materials. Working independently and challenged by the immediacy and physicality of photographing underwater, Sultan describes a sensual and mysterious floating world from a perspective just below the water’s surface.

In 1983 a re-examination of Sultan’s family’s home movies inspired him to explore the motivations and trajectory of his father, who had moved his family from Brooklyn to the San Fernando Valley in the late 1940s. There he became a successful salesman of 20 years, but ultimately lost his job when he refused to move back to the East Coast following a corporate merger. Realized as a book in 1992, Pictures from Home (1983–92) evolved into an examination of the ways in which a narrative is presented. The project gains depth and nuance through the inclusion of Sultan’s writings, which describe not only his questions about representation, gender, and home but also his parents’ reactions to his photographs. Family relationships, identity, and the artist’s aspirations become linked as the lines blur between the parents’ story and the child’s, the dream life and the daily, and the spontaneous and the staged.

The Valley (1997–2003) grew out of a commission Sultan received from Maxim magazine to photograph a day in the life of a porn star in the San Fernando Valley—he found himself in the neighborhood of his youth on the same street where his first crush had lived and two blocks from his high school. Adult film productions regularly rent suburban homes from residents or fabricate them in studios to use as movie sets and the details of each home, along with the subversion of the domestic, captivated Sultan. In this series family photographs and decorative objects coexist alongside the armature of the filmmaking process. Shown between takes, napping, eating, joking, and relaxing, the cast and crew appear almost like an alternate family.

Made mostly in the coastal area of the San Francisco Bay where Sultan had lived since the 1970s, Homeland (2006–9) is the artist’s most overtly landscape-based body of work, highlighting the spaces found on the edge of suburbia. The stylized narratives are acted out by Latino men hired from waiting areas outside hardware stores where they gather to be picked up for manual labor. But here these men are seen possibly engaging in recreational activities or navigating small moments of familial dramas—posed under a tree, maneuvering a skiff, and taking covered dishes to a neighborhood potluck. A fascination with the definitions and implications of home, as well as a longing to create it, is a recurring theme throughout Sultan’s work.

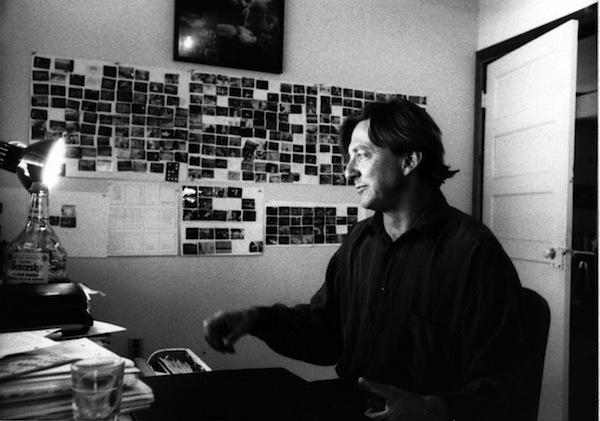

The exhibition also includes a project titled Study Hall, curated by artist and former Sultan student Jon Rubin. Most afternoons in Sultan’s studio, the artist would announce that it was time for Study Hall. For about 20 minutes he and anyone working with him would pick up something to read—nonfiction or poetry, and slightly left or right of their inclinations. With phones and emails remaining unanswered, Study Hall provided a brief nonlinear period of sanctuary and perspective amidst the daily routine. The gallery is equipped with five study carrels each featuring a touch screen loaded with Sultan’s outtakes, scouting shots, reference materials, found photos, and other visual inspirations from his vast archive. As viewers swipe through his pictures each is projected on to the wall creating a constellation of images that reference his interest in chance, context-driven meaning, and the fluid space between private voyeurism and public display.

The title of this piece is inspired by page 184, "Larry's List," of the accompanying exhibition catalogue Larry Sultan: Here and Home.