“I couldn't make any headway in the beginning. I suggested that RAND should dissolve the corporation, or cut off the phones for one day, or have everyone come out in the patios and we'd take some pictures for a day. None of these things got any response.” (1)

This uncanny statement from John Chamberlain on page 71 from A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971 best articulates the infinitely intriguing and the often controversial circumstances of the Art and Technology Program at LACMA—or A&T as it came to be known—from 1967 to 1971. The ambitious enterprise orchestrated by Maurice Tuchman, then senior curator of Modern Art, aspired to empower artists with industrial corporations’ resources and expertise with the intent that these companies could fabricate and/or financially facilitate the creation of something potentially extraordinary. While the four-year program’s collaboration of artists and major industries culminated in just 18 works shown in LACMA’s 1971 Art & Technology exhibition, the catalogue documenting the program’s inner workings became the enduring magnum opus of sorts from the A&T experiment; “the catalogue compiled by Maurice Tuchman in which all the ambitions, negotiations, blocks, and frustrations involved in the immense project are set down, without fear or favor.” (2)

Lionized for its radical transparency of the creative process, A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971 documents project descriptions, correspondence with artists, technical diagrams, process photos, sketches, notes, infamous antidotes of artists working in corporate environments, details of the Pavilion at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, and even the contractual relationships between sponsors, artists, and the museum. This visual evidence, especially things such as the actual reproductions of legalese contracts, is why Report was revered as “the most revealing document yet published on the art and technology symbiosis." (3) Even as the exhibition or the A&T program itself was criticized, the catalogue became admirable for “the degree of candidness.” (4) Tuchman says that he based the book’s design and candor on a government-published report on sexual practices in the United States, believing that “if the U.S. government can be this frank, so can we.” Lou Danziger, who designed the near 400-page catalogue, has no recollection of that report. (5)

Despite the exact origin and all the editorial praise, the book itself is magnificently funky, resembling something between an avant-garde telephone book and a floppy financial audit. Danziger’s deftly executed two-column page structure balances A&T’s sardonic and serious moments. His clean, orderly sans-serif typography juxtaposed against an array of documentary communications offer a dynamic page-to-page scavenger hunt. Over 300 pages of Report are devoted to the participating artists’ projects—indexed in alphabetical order—so the majority of the catalogue allows for a nonlinear reading experience. The book is most interesting when reading about a nonrealized project such as James Turrell and Robert Irwin working with the Garrett Corporation to a concretely executed project such as R. B. Kitaj’s Wings (Recent Sculptures and Buildings).

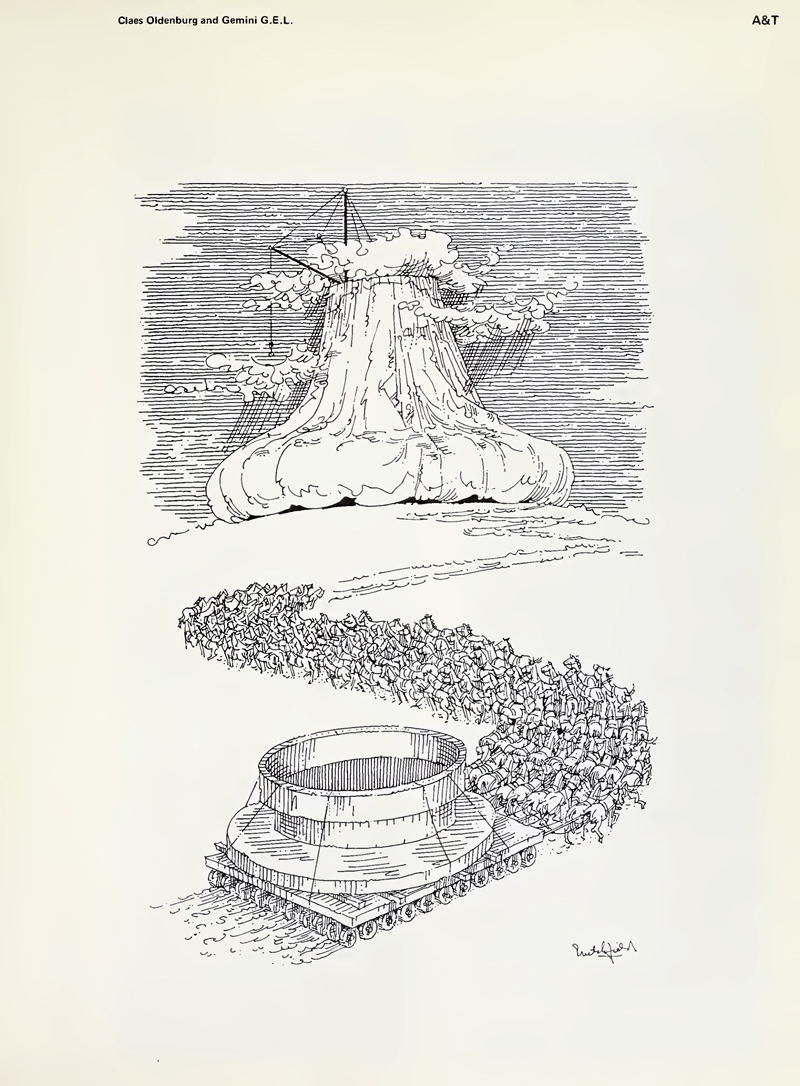

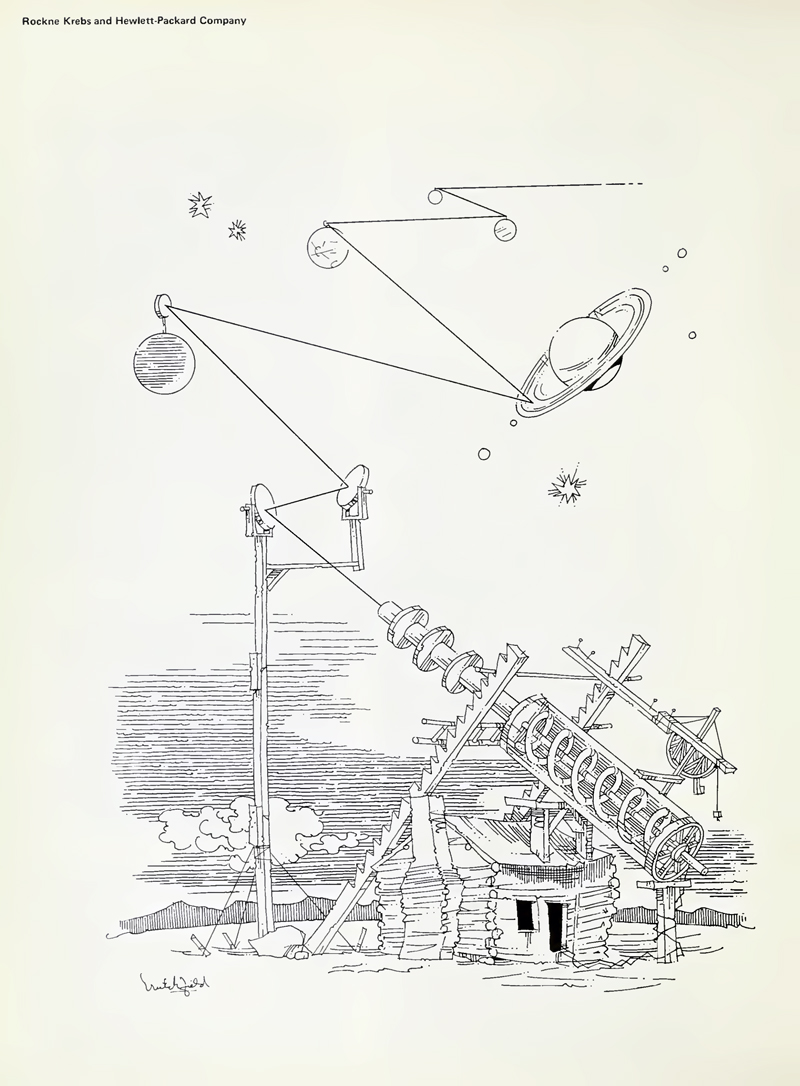

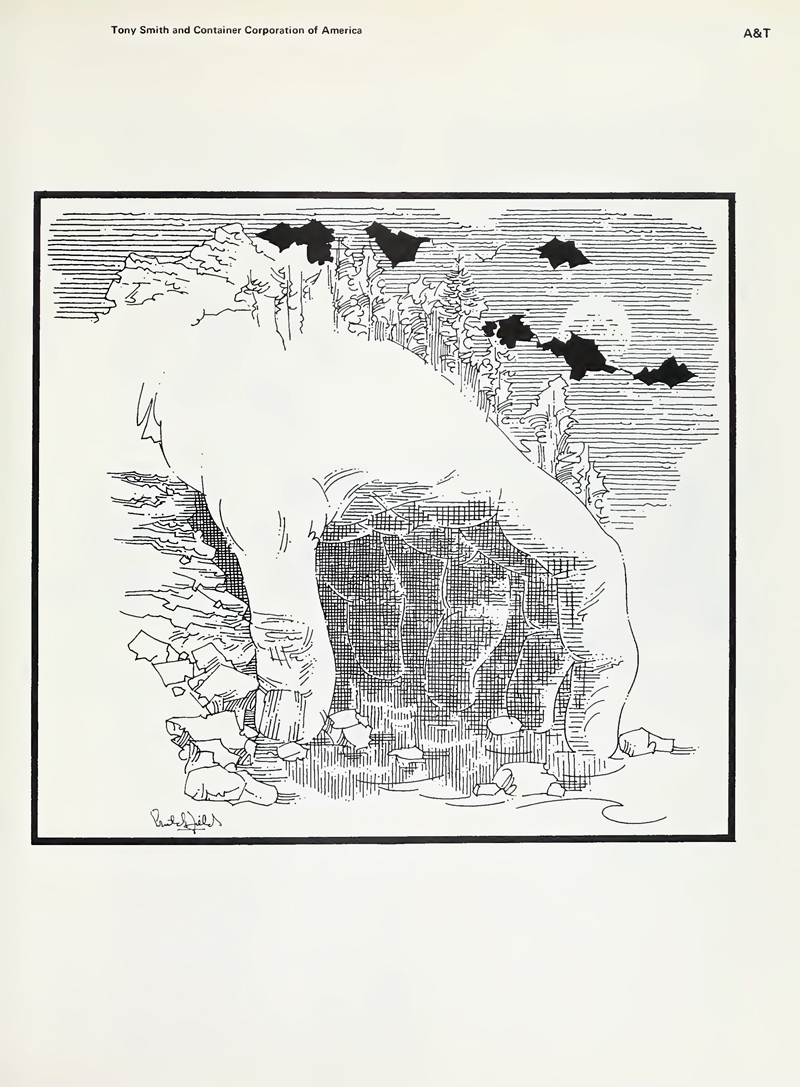

Amplifying the catalogue’s personality are the often-overlooked illustrations by William Crutchfield depicting various artists’ proposals. Tuchman’s introduction, along with fellow curator Jane Livingston’s contemplative essay, Thoughts on Art and Technology, is peppered by 10 imaginative—at times satirical—drawings. Crutchfield’s playfulness radiates through many of the depictions, but one can’t help but see a larger metaphor in his representation of Claes Oldenburg’s kinetic Icebag. The base of the bag, personified as a temple in the vast distance of the background, is awaiting its final crowning plug, which is being dragged up an incline by scores of horses. It is unclear if this ancient visual analogy (to the construction of the pyramids) is anything more than comment about scale, however, Crutchfield’s drawings underscore a graphic witticism about time and technology. The illustrations borrow from the aesthetics of the early 20th century—focused lines, repeated horizontal or vertical directions, negative space, and heavy inking to ground the composition—to speculate on technology of the late 20th century.

Overall the book is spectacular, but the design of the cover spotlights the largest controversy and criticism of the A&T program: lack of diversity. The paperback edition’s cover employs the framework of a checkerboard grid populated by alternating headshots of artists and businessmen; it intended to show the blurring lines of art and commerce. Unfortunately the attempt is overshadowed by the lack of representation of women or people of color. Two women, Aleksandra Kasuba and Channa David (now Channa Hoorwitz), eventually had their proposals reproduced in the book, but the exclusion of women from the A&T program caused protests of the show and most other museum galleries in Los Angeles.

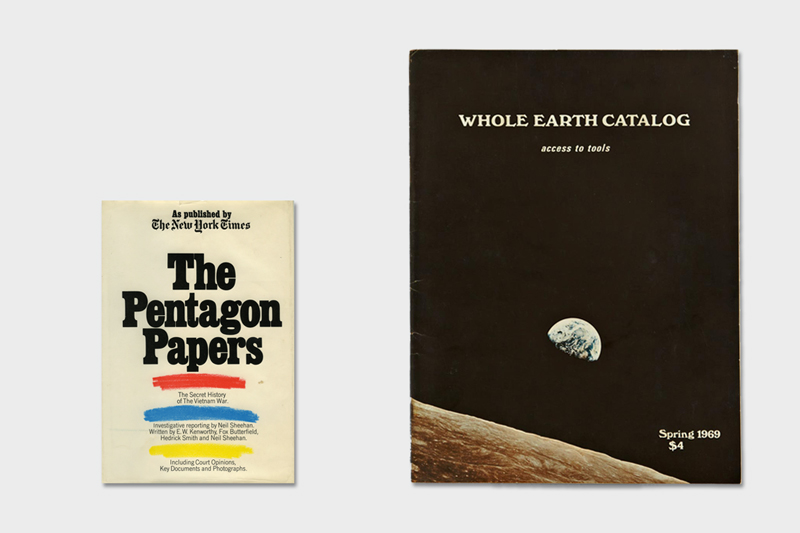

As much as Report’s importance lies in its archiving of compelling work, the book is also a noteworthy graphic and social artifact from the early 1970s. While the A&T program or book wouldn’t exactly be classified as part of any countercultural movement, it shares many basic principles of collaboration, access to tools, and the rationale that "information wants to be free.” There’s no doubt that the Art and Technology publication benefited from things like Stuart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (published between 1968 and 1972) and the leaked Pentagon Papers (1971).

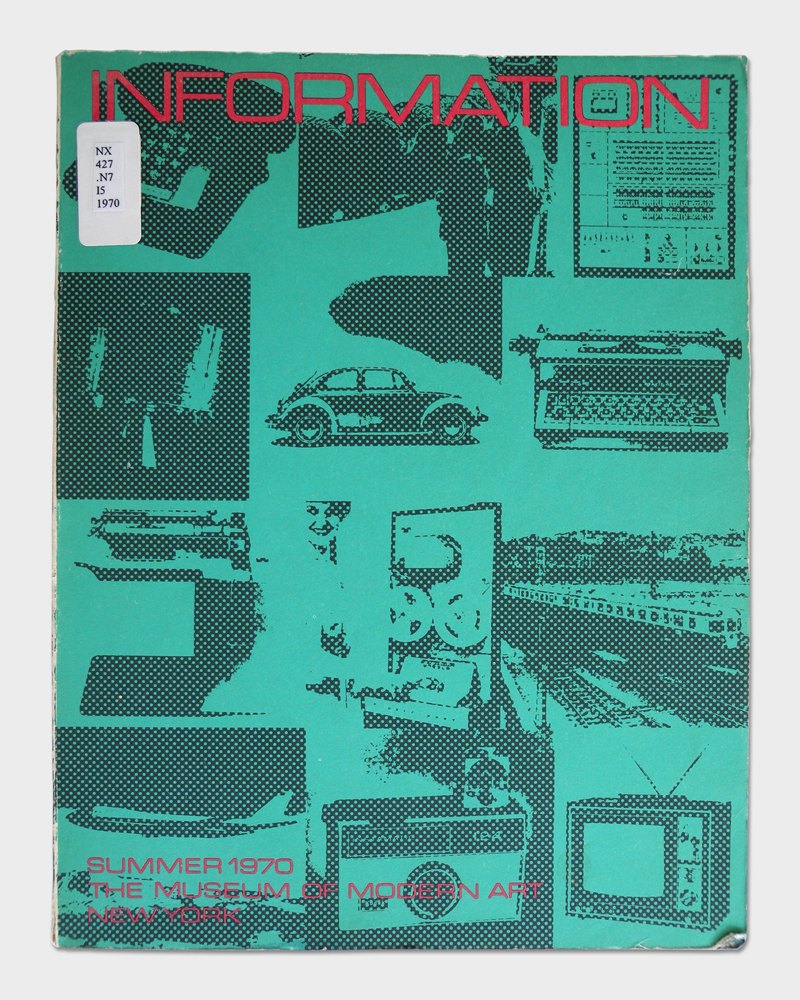

Report also owes something to the Museum of Modern Art’s publication for the Information exhibition—the first major museum exhibition of conceptual art, which opened in the summer of 1970, a year before A&T.

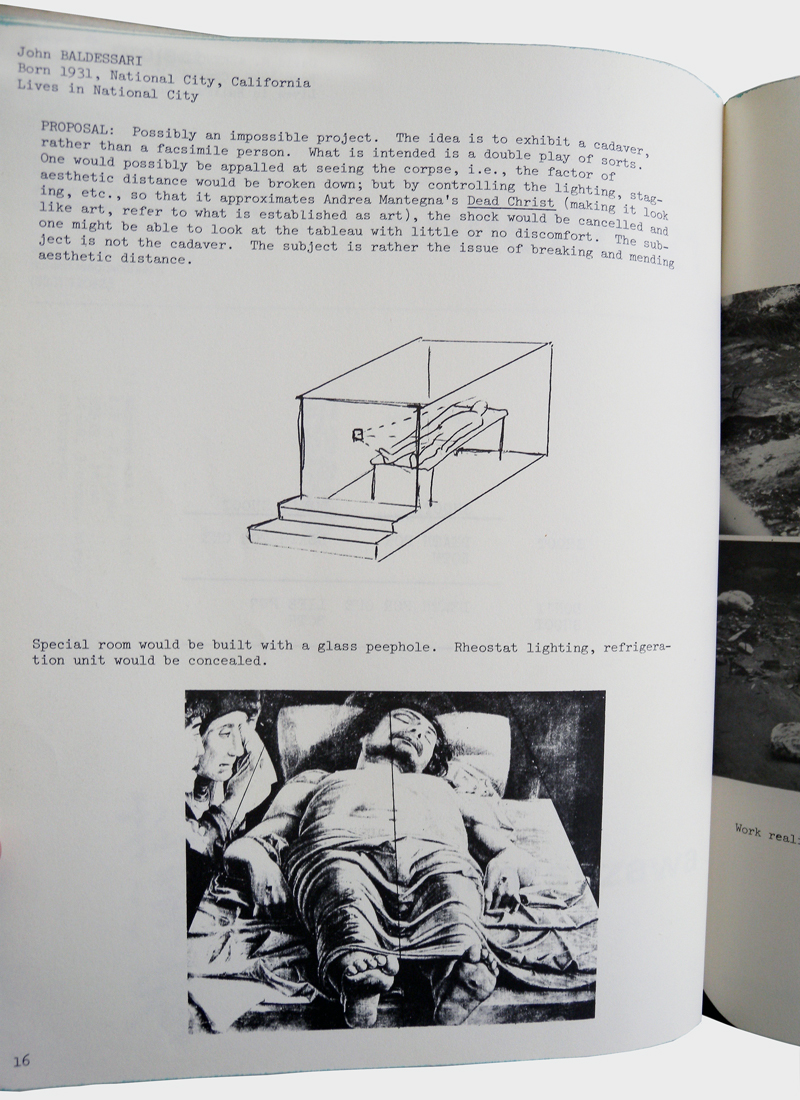

In the preface to Information, curator Kynaston McShine states that MoMA wanted this exhibition to be “an international report” on the state of art at that time. Tuchman titled his catalogue A Report on their Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971. (6) McShine later notes (in what would be the main essay of the publication), “this book is essentially an anthology and considered a necessary adjunct to the exhibition.” (7) Tuchman’s A&T is a compendium to the entire A&T program and exhibition. McShine’s and Tuchman’s book are not precious objects; indeed the materials used include cheap newsprint-like paper, one-color printing (black), and sporadic reproductions of typewritten documents. These production elements—while fashionable for many countercultural publications of the day—could still be read as undervalued for an “art catalogue.” Hilton Kramer, then chief art critic for the New York Times, described the Information publication as a “souvenir album which McShine has put together in lieu of a catalogue for the exhibition.”

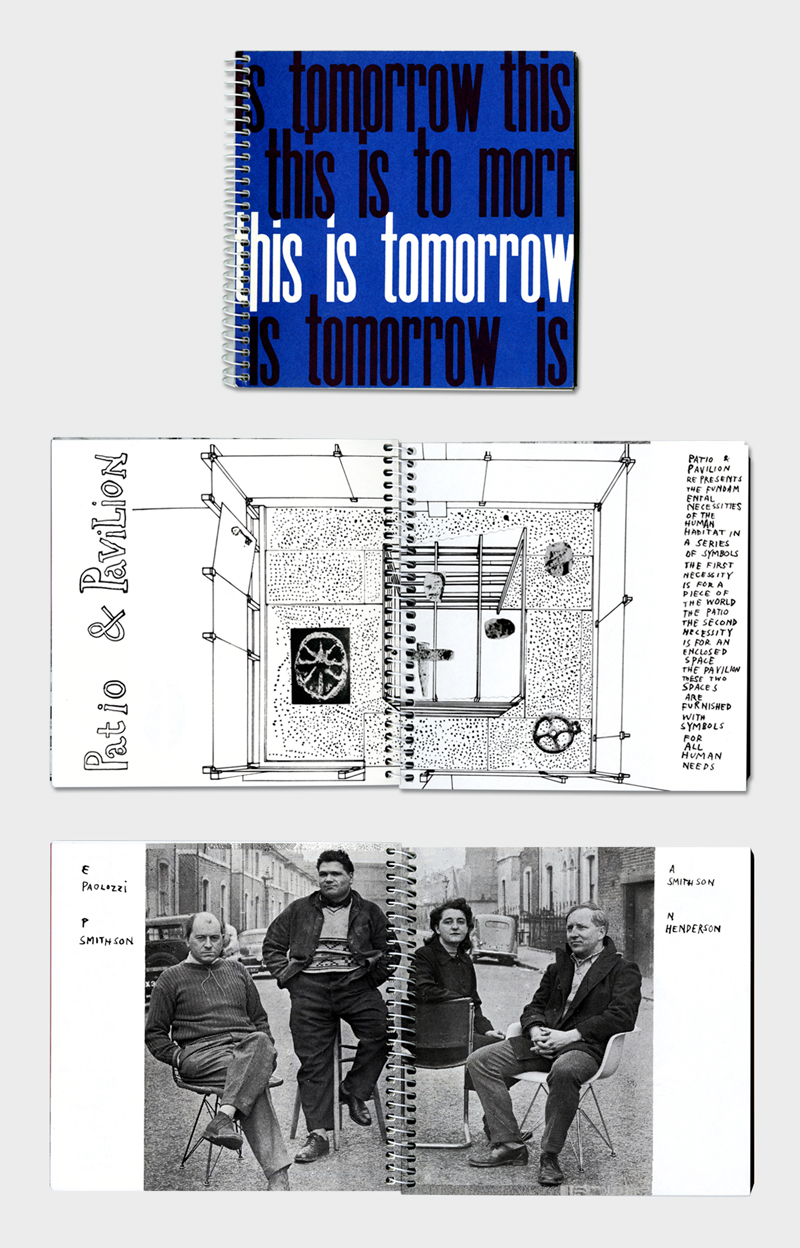

We can extract important questions from Kramer’s snide remark: How should an exhibition catalogue function? What are their ultimate purpose? Both McShine’s and Tuchman’s publications share a sense of era, methodology, and production. They may also be interconnected to larger aspects of time, place, and cultural attitudes. In thinking about the connection between these two publications, I’m reminded of the visually frenetic catalogue (which was, and is, considered an important piece of graphic design) (from Anne Massey's essay "This Is Tomorrow and Beyond," published in 1995) for the seminal This Is Tomorrow group exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in August of 1956.

A multidisciplinary exploration of collaboration, This Is Tomorrow brought together 36 architects, painters, sculptors, and other artists—including 12 members of the Independent Group. (8) The exhibition presented 12 exhibits by 12 groups in an attempt to challenge visitor’s notions of conventions of art and design through chaotic environments. The catalogue is an experience in itself. The 6.5 x 6.5–inch spiral-bound book, designed by Edward Wright, simulates the graphic cacophony of the show. The catalogue featured essays by Reyner Banham and Lawrence Alloway, and each group submitted their environment’s floorplan, a statement, and self-portrait. A facsimile was reprinted in 2011 and contains this relevant statement about exhibition books printed in its preface:

“Exhibitions can offer rare glimpses of both an aesthetic and social milieu. The trappings of the exhibition— invitation cards, leaflets and most critically catalogues—embody an invaluable archival resource. They tell us not only about the scope of works on show, but who showed with whom, the graphic style of the day and styles of writing." (9)

A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971 is unconventional, but vital for understanding the A&T program in its totality. The book’s organization is an epic achievement for Maurice Tuchman; collaborators Hal Glicksman, Jane Livingston, and Gail Scott;, and LACMA. Not only does it document a significant part of the museum’s history, a matrix of importance artists’ projects and creative process, but it’s a surviving monument from an important time and place worth reading about.

View the book and check out the exhibition, which features ephemera from the A&T program. On view on the second floor of the Ahmanson Building through October 18: From the Archives: Art and Technology at LACMA, 1967–1971.

(1) From Maurice Tuchman's essay on John Chamberlain in A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971.

(2) From Time magazine's article "Art: Man and Machine" from June 28, 1971.

(3) From Jack Burnham's article "Corporate Art" from the October 1971 issue of Artforum.

(4) From Jack Burnham's article "Corporate Art" from the October 1971 issue of Artforum.

(5) From the 2008 book The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

(6) From the 2008 book The Broad Contemporary Art Museum at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

(7) From McShine's essay in the Information catalogue published in 1970.

(8) From Anne Massey's essay "This Is Tomorrow and Beyond," published in 1995.

(9) From Nayia Yiakoumaki and Iwona Blazwick's preface for This Is Tomorrow, published in 2010.