Situated between the end of World War I and the Nazi assumption of power, Germany’s first democracy thrived as a laboratory for widespread cultural achievement, witnessing the end of Expressionism, the exuberant anti-art activities of the Dadaists, the founding of the Bauhaus design school, and the emergence of a new realism.

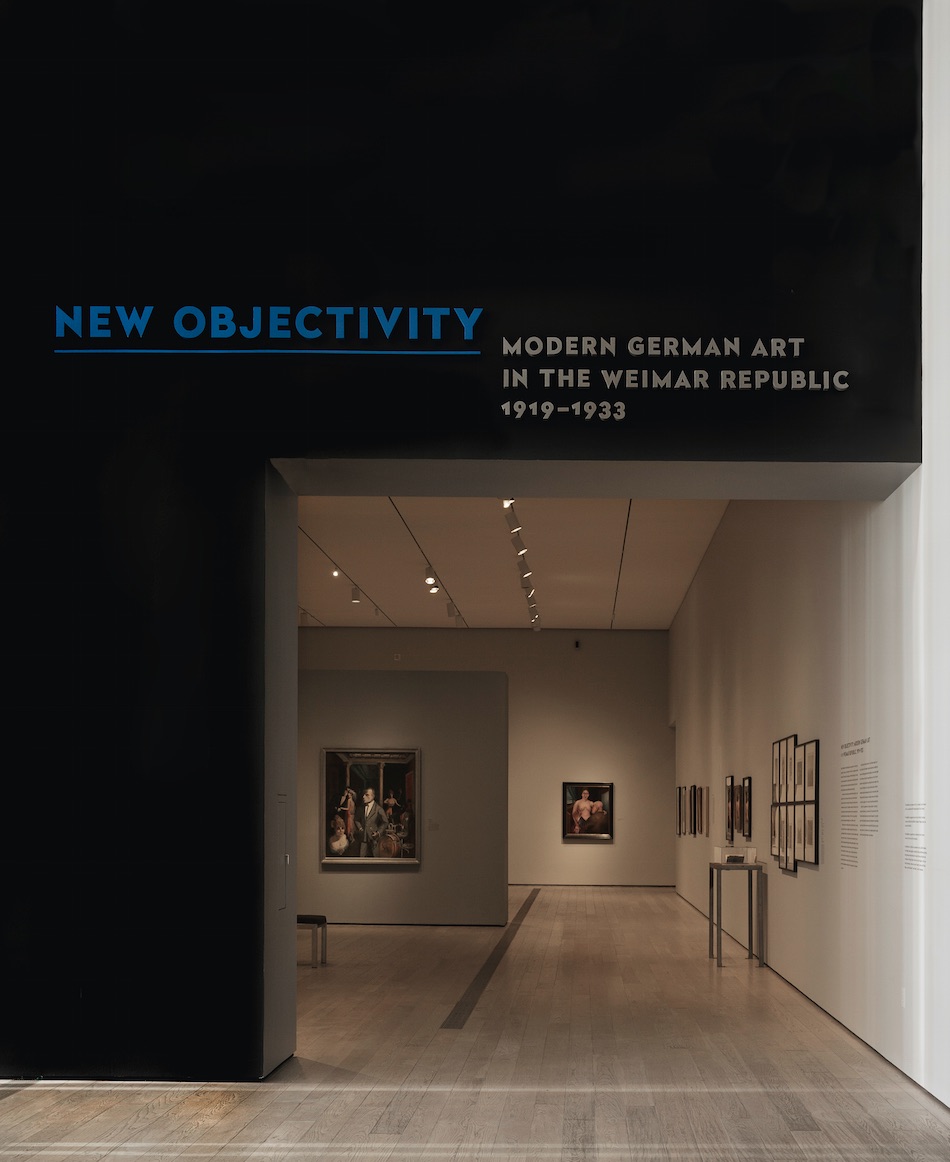

Yet the fourteen years of the Weimar Republic (1919–33) also witnessed unprecedented social, economic, and political ruptures. Bringing together nearly two hundred paintings, photographs, drawings, and prints by more than fifty artists, New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 examines the varied ways the artists of this period displayed their disillusionment with the past, engaged in sharp social critique, and sought to make sense of a rapidly changing modern society.

World War I had left the German economy and morale in shambles, with close to 2.5 million military and civilian deaths, with millions more injured or disabled. While German Expressionist artists had for the most initially embraced the war, soon they were profoundly shocked by the shattering realities of the battlefield and the carnage they witnessed. It was in this context of the complicated political realities of the new Germany that increasing numbers of artists moved away from the Expressionism of the prewar period and turned instead toward realism. This newly grounded, sober view of everyday life formed the basis of what was dubbed Neue Sachlichkeit—New Objectivity.

The situation through the early 1920s was volatile; by late 1922, for example, inflation began to skyrocket so high that a single egg would eventually cost 100 billion marks. Conditions began to improve gradually toward the end of 1923, leading to a period known as the Golden Twenties. With inflation reined in and the economy on an upswing, discretionary income flowed to an array of consumer goods and leisure activities, and personal, sexual, and social freedoms flourished—all of which supplied ample subject matter for artists. But the Wall Street crash in October 1929 and the ensuing worldwide economic depression were disastrous for the country, provoking a crisis of widespread bankruptcies and unemployment. The remaining years of the republic were marked by instability and street violence, culminating in the rise of the Nazi Party. With Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in January 1933, the Weimar Republic was dead, and the New Objectivity period in art was effectively over.

Exhibition and Concept

While they were not unified by manifesto, political tendency, or geography, New Objectivity artists did share a skepticism regarding the trajectory of German society in the years following World War I. New Objectivity: Modern German Art in the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933 presents figures whose careers are central to twentieth-century German modernism (Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and George Grosz) together with those whose achievements may be less well-known internationally but who are nevertheless closely associated with this particular form of realism (for example, Aenne Biermann, August Sander, Christian Schad, and Georg Scholz). The exhibition is divided into five thematic sections that address competing and at times conflicting approaches that these artists applied to the tumultuous Weimar years. Some of the works attack political and social wrongs; others appear nostalgic for the past; still others focus on objects, rendered in uninflected surfaces and seemingly frozen in time. Further, by presenting photography alongside painting and drawing, this exhibition offers the rare opportunity to examine both the similarities and differences between New Objectivity’s different media.

The first section, “Life in the Democracy and the Aftermath of the War,” depicts both the collateral sufferers of the upheaval of the early days of the republic as well as those with power who benefited from the deprivation and chaos of the period. For artists such as Otto Dix, this may have been a way to confront the trauma of personal wartime experiences on the front. He, along with many other artists, depicted urban landscapes populated with men and women in desperate circumstances. The blind or amputee beggar, a common sight at the time, acted as a stand-in for a society irreparably scarred by war. Prostitution was widespread, as was sexual aggression and violence. Many of these works emphasize the ugly and the grotesque as an intentional affront to comfortable bourgeois society, as in Dix’s Prostitute and Disabled War Veteran/Two Victims of Capitalism. Other works cast a critical eye on those who actually benefited from the instability of the early Weimar years, such as Heinrich Maria Davringhausen’s The Profiteer.

The second section, “The City and the Nature of Landscape,” explores the tensions between the rural and the urban. The connection between the rapid encroachment of twentieth-century industrialization and nostalgia for the supposedly simpler, bucolic life of the nineteenth century is present in the landscapes of artists such as George Schrimpf and Erich Wegner. Other works focus on the twentieth-century city, including its modern architecture (concrete, steel, and glass), mass advertising, and modes of transportation, but the mood is predominantly one of stillness and displacement rather than dynamism. In his paintings of urban settings, Anton Räderscheidt created a sense of eerie tranquility that manages to be simultaneously hyperreal and unreal. In his House No. 9, for example, two figures (the artist and his wife) depicted with formal simplicity appear unconnected, even isolated, in front of their own home.

Section three, “Man and Machine,” examines artists’ attention to the technological progress and industrial modernization of the period—a fascination that was often tinged with skepticism. New Objectivity representations of industry fluctuate between recognizing the transformative power of new technologies and conveying the lack of humanity embedded in contemporary industrial practices. Photographers and painters rendered machines with formal beauty and rigorous clarity, as in Albert Renger-Patzsch’s Steam Engine Camshaft and Carl Grossberg’s The Paper Machine. Time seems frozen; the actual human labor associated with the machinery is often invisible and the anonymity of technology prevails.

“Still Life and Commodities,” our fourth section, looks closely at new iconographies and that New Objectivity practitioners developed in contemplative studies of everyday objects. Artists focused on banal items (a dish towel, a broom, a bucket), modern appliances (an electric coffee pot, a sewing machine), or botanical species or organic forms (a rubber plant, a basket of onions). Aenne Biermann’s Eggs is typical of her sharply lit, tightly cropped photographs that present commonplace objects almost as abstract compositions. Georg Scholz’s Cacti and Semaphore is practically a domestic snapshot of the new Germany, with its exotic plants that had recently become fashionable for home décor, mass-produced light bulbs signaling the ubiquity of electricity, and railway semaphores (visible through the open window) standing for modern transportation and communication.

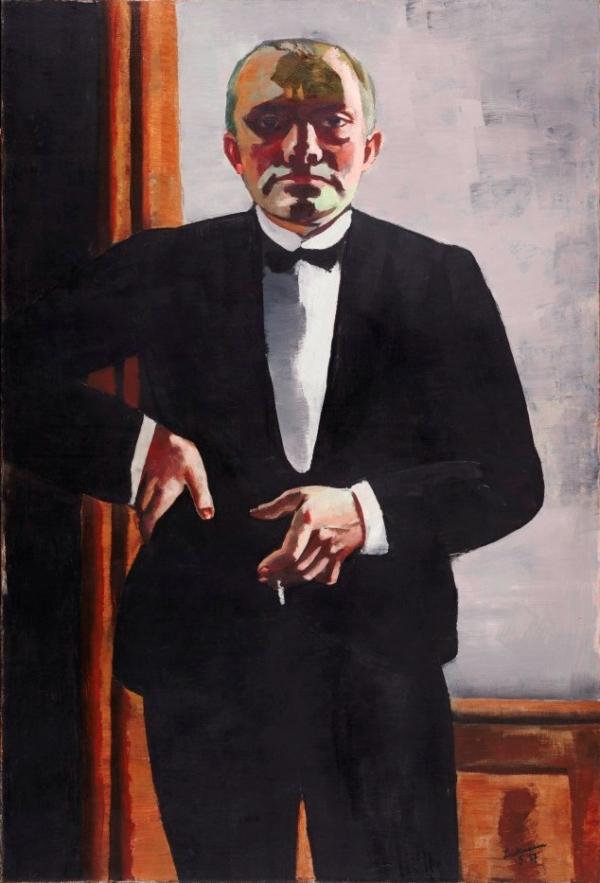

The final section, “New Identities: Type and Portraiture,” explores the work that is perhaps most commonly identified with New Objectivity. In unsentimental works that defied traditional portraiture, artists frequently took as their subjects the social types of Weimar Germany. Otto Dix’s The Jeweler Karl Krall, for example, portrays his subject in an affected stance, torqued into a feminine pose and possibly wearing makeup; the overall impression is one of an unmistakable display, at a historical moment in which homosexuals were becoming more visible culturally. A number of New Objectivity artists also seized the opportunity to explore the self with the same unsentimental precision with which they approached the world around them. In Christian Schad’s Self-Portrait, the artist portrays himself and a model whose state of undress suggests that a sexual encounter has occurred, yet the figures appear completely divorced from one another, creating a provocative tension. Max Beckmann adopts the clothing, stance, and haughty expression associated with the upper class in his Self-Portrait in a Tuxedo, creating a portrayal that is both enigmatic and self-absorbed.

Photography was well suited to the aims of New Objectivity. One of its most important practitioners was August Sander, who recorded his many subjects in somber, unexpressive poses, which he then arranged according to profession, such as Cleaning Woman, Pastry Chef, and Bricklayer. Besides traditional occupations, Sander also chronicled the new professions of modern society, as in his Secretary at West German Radio in Cologne. With her bobbed hair, loose clothing, and confident gaze, she depicts so-called “New Woman” whose entrance into the workforce emancipated her from many of the restrictions faced by women before the war. She, like all of the faces captured in Sander’s unfinished series, forms part of an indelible archive of Weimar society.

At a time when contemporary art and popular culture alike are preoccupied with documenting “the real,” it is worth taking a fresh look at how artists in the 1920s grappled with the uses of realism to make sense of their own fast-changing world. A close examination of this fascinating period yields new insights into a complicated chapter in both German art and German history. With very different backgrounds, these artists eschewed the emotion, gesture, and ecstasy of Expressionism, and sought instead to record and unmask the world around them with a close, impersonal, and restrained gaze. Together they created a collective portrait of a society in uneasy transition, in images that are as striking today as they were in their own time.