Unframed is inviting curators with different specialties to discuss a single work of art or an exhibition on view. Today, associate curator of contemporary art Christine Y. Kim writes about Southern California's mark on Korean-born artist Young-Il Ahn's practice. Check out assistant curator of Korean art Virginia Moon's post on the traditional and not-so-traditional influences on Ahn's work.

1966 was a hallmark year for young artists working in Southern California. As it had been for many European artists from previous centuries, such as Caravaggio, Vermeer and Monet, light was a foremost preoccupation of many artists in Los Angeles. The abundance of sunshine and the horizon of the Pacific coast made it an ideal site for those exploring light. Employing the medium of light itself, James Turrell (b. 1943, Los Angeles) moved into the former Mendota Hotel on the corner of Hill and Main Streets in the Ocean Park neighborhood of Santa Monica in 1966. There he cut his first sharp-edged apertures through the exterior building walls to see the unobstructed sky during the day (Sky Window, 1966) and the movement of the street lights and headlights at night (Mendota Stoppages, 1969–74).

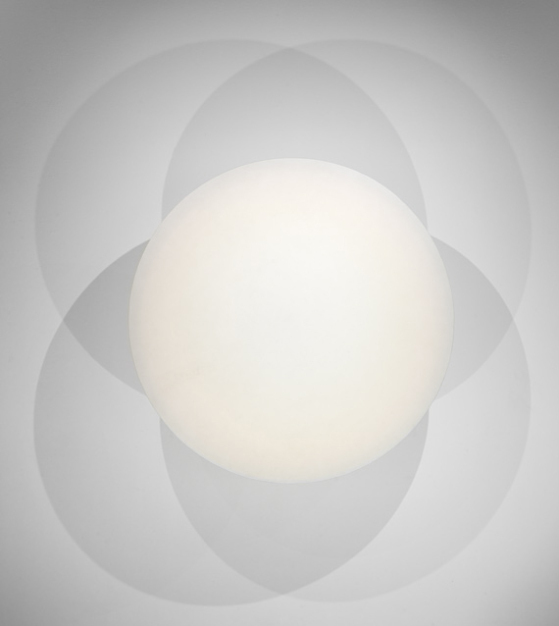

It was the same year that Robert Irwin (b. 1928, Long Beach) began painting on aluminum disks with a convex structure affixed to the wall. Fusing sprayed color with properties of light, the disks seemed to both hover and dissolve into the natural light of their surroundings. Foreign-born artists like Maria Nordman (b. 1943, Gorlitz, Germany), known for her light-filled installations, also flocked to Southern California to probe the land- and seascapes of the Pacific coast. In 1966, she began filming her seminal work, Filmroom: Smoke (1967) on the beach in Santa Monica for which she aligned the filmic picture plane with earth and water along the Los Angeles coastline.

The Hart-Celler Act of 1965, which abolished the previous immigration policy favoring western Europeans, marked a shift in immigrant populations of the United States as it allowed more individuals from Asia and South America to enter the country. Among the many Koreans who immigrated to Southern California during that wave, painter Young-Il Ahn (b. 1934, Kaesong, Korea) arrived in 1966. “When I beheld my new home with its incredibly vast spaces running along the deep blue Pacific,” he recalls, “I felt a great sense of relief and joy.” Beginning in the 1980s, he painted nearly 400 works as part of his Water series, inspired by the light on the Pacific Ocean. Ahn explains:

Beyond the distant horizon, the endless, vast ocean, that boundless space! As an artist who had spent his whole life seeking beauty and trying to express it, I was moved by the ocean's ability to radiate such profound beauty at any given moment. As the rays of the sun tumble into the ocean, the light spreads in an array of colors as if through a prism. At times, the light may reflect brilliantly and at other times it shimmers with more subdued intensity. The constantly moving atmosphere, the shifting sounds, the changing shape of the waves, light and color changing moment by moment—there is no moment when it can ever stop and no moment can ever look the same as the process of change and rebirth goes forward and yet. . . and yet the sea never changes and is forever constant. So, when I look out upon the ocean, I tremble as if I am holding part of the universe in my hand.

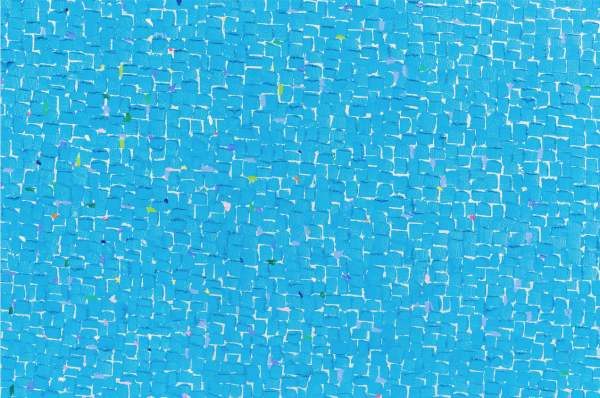

Describing himself as a very private person, Ahn did not socialize much with other local painters who were also exploring light, color, and movement but was well aware of their work. He deeply admired the work of Sam Francis (1923–1994), whose sensitivity to the reflection and refraction of light on water can be seen in "all the shimmering qualities . . . brought to the surface of the canvas," as described by Debra Burchett-Lere, co-curator of Francis’s 2013 retrospective at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. "You feel like you are stepping into a waterfall . . . or that you're stepping into a cloud mass, or looking at some continent forms, or that there are meteors falling through the sky." The same can be said of Ahn’s Water SZLB15 (2015) now hanging in the Korean art galleries at LACMA. Focused on the radiating and pulsating energy of light on the water’s surface, Ahn endeavored to translate the experience of light, liquid, and color to oil on canvas.

Richard Diebenkorn (1922–1993) also moved to Southern California in 1966. Inspired and invigorated by Francis’s light-soaked studio and the Southern California coast, Diebenkorn began his Ocean Park series that year, which resulted in nearly 140 of his most celebrated paintings, named after that particular community in Los Angeles. Abandoning the figure altogether, these works were, according to the artist himself, “still representational, but . . . much flatter.”

This flatness is also a critical element of Ahn’s Water SZLB15. While the composition is cool, flat, and meditative, the topography of its brushstrokes and shimmering flecks of lavender, tangerine, and grassy hues are palpable and seem to glow. While Ahn’s work grew out of abstract and monochrome languages of contemporary art in Korea of the 1950s and ’60s, his sensibility is inextricably bound to the Southern California landscape and seascape and to contemporary American art since the 1960s. “I have been deeply changed by living the past half century in California,” says Ahn. “As long as I live I'll look to put on canvas ideas that reflect the transformation which California has made in me.”

Young-Il Ahn's Water SZLB15 is currently on view in the Korean art galleries.