Reconstituted from fragments dating to the second century, the Stowe Vase has been a source of artistic inspiration since its excavation near Rome in 1769. It was etched in the 1770s, rendered in silver in the early 1800s, and inspired a 3D-printed artwork in 2016. Brought together for the first time, the different versions on view in the exhibition The Stowe Vase: From Ancient Art to Additive Manufacturing offer a unique visual experience. Their arrangement along the north-south spine of the gallery allows for striking sightlines in which the silver vase can appear superimposed upon both the marble and the 3D-printed vase in turn.

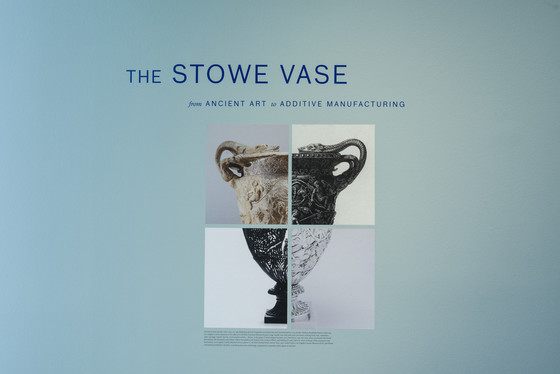

Viewed separately, their shared design is undeniable. Seen together, their differences reveal the creativity involved in translating a highly distinctive design across two millennia. The composite image created for the introduction wall of the exhibition celebrates this singular opportunity to compare and contrast these related works.

The stitching together of four photographic details of the different versions of the Stowe Vase is an incitement to look more closely at the objects on display. The manipulation of scale needed to align the images highlights the difference between seeing the actual objects and the photographic reproductions. By examining the real objects in the physical space of the museum, we can see how each iteration of the design required individual choices specific to the medium, moment in time, and motivations of the maker.

Measuring over seven feet tall on its pedestal, the Stowe Vase is monumental in scale. Carved in low-relief around its body, winged cherubs frolic among grapevines. Forming its handles, four serpents carved fully in the round emerge from acanthus foliage to rest their toothy grins upon the vase’s rim. This combination of grapes and snakes refers to the Roman god Bacchus, who died and was reborn like a snake sloughing off its skin, and whose rituals included copious amounts of wine.

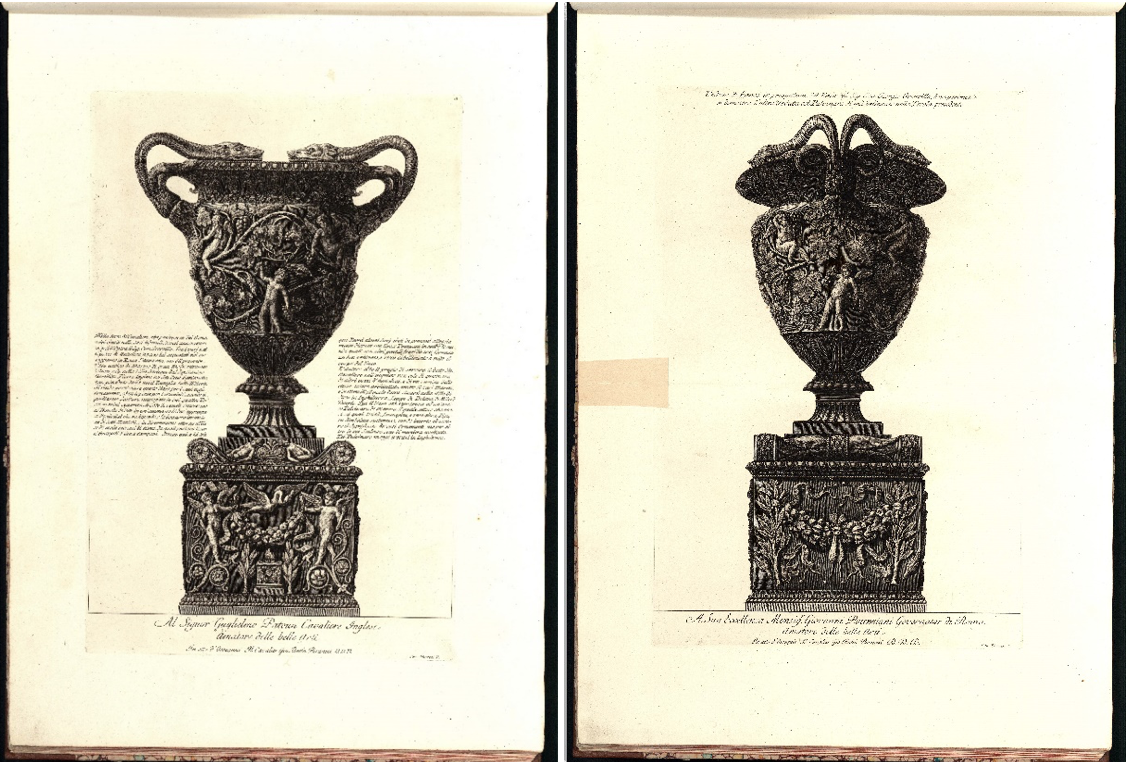

It is an imposing sculpture whose form is recognizable from a distance and dominates the gallery space. The two etchings made shortly after its restoration are still large but only a quarter of the size, and warrant closer inspection.

The illusion of three-dimensionality in these two-dimensional works on paper is intensified by their portrayal of the vase under dramatic raking light. The printmaker has also taken liberties, and chose to show the vase atop a more elaborate pedestal. Although the inscription on the main view explains how the vase was discovered adjacent to the ruins of Emperor Hadrian’s villa by archaeologist Gavin Hamilton and was subsequently sold to George Grenville for the grand English country residence Stowe House (to which Grenville was heir), it is dedicated to the English gentleman and collector William Patoun. This is because the prints belong to a larger group of images of vases and other decorative sculpture produced by architect, designer, and antiquities dealer Giovanni Battista Piranesi to promote himself to prospective clients such as Patoun (which also explains the pedestal upgrade). Associated with the mostly British aristocracy who could afford to study and own the remains of Italy’s classical past, Piranesi’s prints became admired as intellectual souvenirs in their own right.

They also became models for craftspeople catering to the expanding upper class taste for things that looked archaeological. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, British metalworkers excelled at producing vessels in the form of well-known excavated artifacts. This magnificent representation of the Stowe Vase was made by the leading London silversmith Paul Storr, who had a copy of Piranesi’s album of vases and other antiquities in his workshop. The serpent handles and raised cherubs among vines were cast and soldered onto the body, which was itself hammered from a sheet of precious metal. Tiny punch marks with different profiles were then meticulously tapped over the surface to achieve the subtle textures of feathered wings, velvety leaves, and scaly skin. Though also smaller in scale than the original marble model, this silver version of the Stowe Vase possesses even finer detail.

Michael Eden chose to make his version of the Stowe Vase in coated nylon. While silver still indicates wealth and luxury today, modern synthetics are the materials most associated with the contemporary production technologies of 3D printing that present new opportunities for creative explorations. Working from his studio in England’s picturesque Lake District, Eden used 3D digital software to draw the form of the vase by eye from two-dimensional photographs of it. Eden then developed a two-dimensional cut-out pattern through close study of Piranesi’s representation of the vase’s decoration, which he then used to pierce his three-dimensional model of the vase. The pattern references Piranesi’s meticulous, parallel, etched lines, inviting a comparison between the printing technologies of the 18th and 21st centuries. Eden’s choice to pierce rather than wrap the decoration results in distortions around the sides, intended to draw attention to the differences between two-dimensional and three-dimensional perception. With the original marble vase’s Bacchic imagery in mind, he calls this piece the Innovo Vase, which translates from Latin as renew, innovate, start again, or return, which also recalls the excavation and reconstitution and subsequent reworkings. Eden’s work thus initiates a dialogue with the other iterations of the Stowe Vase, and highlights the legacy of this idiosyncratic design.

Read more about Michael Eden’s Innovo Vase and visit The Stowe Vase: From Ancient Art to Additive Manufacturing before it closes on September 5.