The recent gift to LACMA by Dorothy Lichtenstein on the occasion of the exhibition The Serial Impulse at Gemini G.E.L. brings to the museum a series of color woodcuts done in 1980 that, in part, owes its very existence to works that are now in LACMA’s collection.

During a visit to L.A. to work at Gemini in 1978, Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein were invited to dinner at the home of longtime friend and collector Betty Asher. Also invited to the intimate dinner party was German Expressionist collector Robert Rifkind. (I worked with Betty in the late 1970s at LACMA when she was curatorial assistant in the Department of Modern Art, and she invited me as well.) During the course of the dinner Roy and Bob got into a conversation about how the German Expressionists, and in particular the Brücke artists, were passionate about working in woodcut, cutting blocks and pulling prints themselves in their intimate studios in Dresden and Berlin in the years before the First World War. While Roy was of course familiar with their works, he had never studied them very closely. Bob offered to show Roy some of the best examples of woodcuts by Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff if he would make time during his trip to visit the Rifkind Collection, which was then housed within the Rifkind law offices in Beverly Hills. His curiosity piqued, Lichtenstein made arrangements to spend an hour or two at the collection. After the initial visit, the two spent many, many hours handling the prints and looking closely at the dozens of the woodcuts in the collection. For the collector, it was a joy to share the prints with an artist who was such an astute and close viewer. For Roy, the experience was a rare opportunity to handle the prints himself and to spend as much time with them as he wanted.

Two years later, on one of his many visits to L.A. to work at Gemini, Roy called Bob and invited him to see what he had been up to there. What Bob saw were the first works in the Expressionist Heads series, and he was thrilled to see what Roy had done.

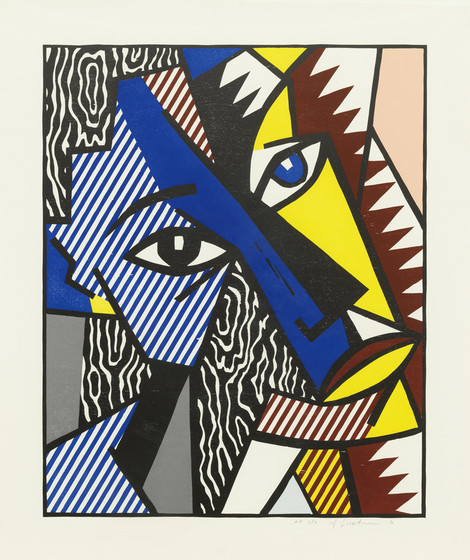

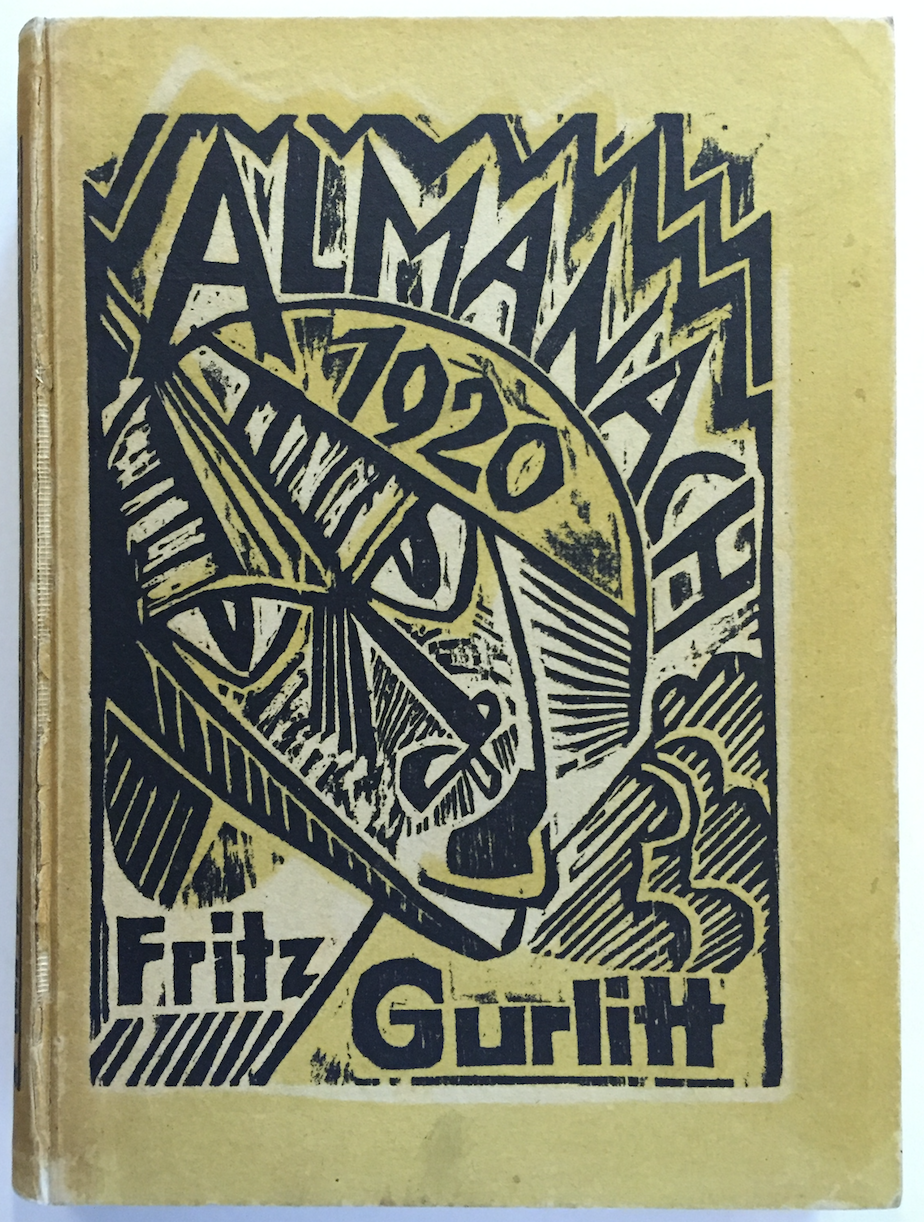

Head, a seven-color woodcut, is perhaps the most compelling of the series. The sharply carved lines define a face that projects from the picture with barely contained excitement. The juxtaposition of the various textures—smooth, woodgrain, simulated wood grain, and rough jagged lines—and seven distinct colors all contribute to its power. It’s interesting to compare Lichtenstein’s Head with one that Max Pechstein illustrated for the cover of Fritz Gurlitt’s Almanac of the Year 1920, also in the Rifkind Collection. While Lichtenstein’s head shares the same angular face, it seems almost a stylization of the Pechstein. While the Expressionist woodcut has an unbridled and an awkward quality, Lichtenstein’s print is more controlled and beautiful, though perhaps not as raw and powerful.

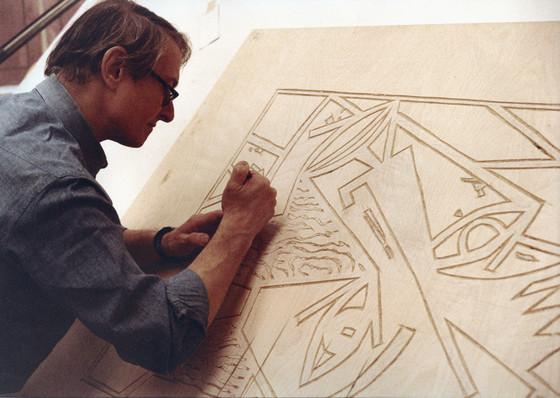

Lichtenstein has taken the energized lines of Pechstein’s image and translated them into stylized compositions of interlocking colors, shapes, and textures. (Interestingly Lichtenstein also created a small private edition in black; the Expressionists, too, often pulled both black-and-white and color states of the same woodblock.) Lichtenstein began his woodcuts with small colored pencil sketches, which he enlarged with a projector to the scale he wanted to work with. He then drew the image onto tracing paper. Using Baltic birch—a very hard wood—he cut across the grain to create the smoothest surface possible. He then worked each of the colors successively, beginning with black and ending with dark blue. Finally, he had the black central image embossed to give it a richer feeling; the paper, which had become quite smooth during the printing, was embossed to restore the feeling of textured, handmade paper. Tony Zepeda, the printer at Gemini who worked with Lichtenstein on the series, recalled that the artist manipulated the woodblock, the imprint of the grain, and the solid, even coloration to achieve the effect he wanted—quite a different approach from those early German Expressionists who spontaneously and directly carved their images on woodblocks and pulled the prints themselves in their small studios.

We have now come full circle, with these seven powerful woodcuts entering LACMA’s collection, which has housed the Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies since 1983. It offers a wonderful occasion to connect more recent work by an important American artist with the specific historical artworks that inspired him.

* Some of this text is based on interviews I conducted in conjunction with an article published in the September 1982 issue of Artnews magazine.

Visit The Serial Impulse at Gemini G.E.L. at LACMA, on view through January 2, 2017.