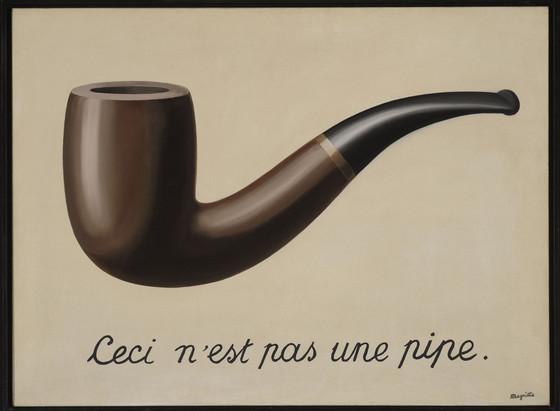

Recent visitors to LACMA who are familiar with our permanent collection of modern art, housed on Level 2 of the Ahmanson Building, may turn a corner and find themselves exclaiming: “That’s not the pipe!” Indeed, René Magritte’s recognizable surrealist masterpiece The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe) (La trahison des images [Ceci n’est pas une pipe]) (1929) is currently on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, in their exhibition René Magritte: La trahison des images, until January 23, 2017. As one of the most iconic and influential works of 20th-century art and one whose image has permeated popular culture, Magritte’s pipe has been a favorite among LACMA’s diverse audiences since its acquisition in 1978.

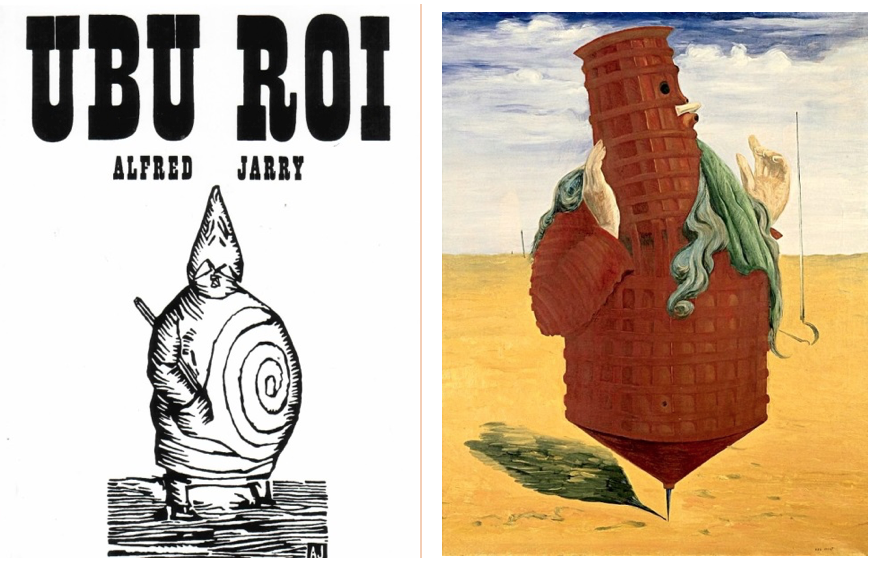

Though we will miss our Magritte while it’s visiting Paris, we are thrilled to be able to present another painting in its place. In the spirit of collegiality and reciprocity, the Centre Pompidou has in turn lent LACMA Max Ernst’s Ubu Imperator (1923), affording our visitors the opportunity to see the work of another surrealist master. Ernst, a German artist and founding member of the Cologne Dada group in the late 1910s, painted Ubu Imperator shortly after moving to Paris in 1922, where he became a leading proponent of surrealism. In the painting, Ernst makes effective use of the compositional logic of fragmentation and fusion that he first employed in his Dada collages from 1919–20: the picture features a pieced-together figure comprising disjointed elements, and who incongruously inhabits a desert terrain. The cylindrical form, part human and part man-made, is fundamentally unstable: its base is a spinning top and its head resembles the Leaning Tower of Pisa, which slants away from the scythe on the right-hand side of the frame. Useless in the barren setting, the scythe lends an ominous tone to the scene.

Characteristic of Ernst’s work from the 1920s and of the visual vocabulary of surrealist painting more broadly, Ubu Imperator’s imagery is rooted in the artist’s dreams and childhood memories. It also includes allusions to psychoanalysis and literature—the title, which means “Commander Ubu,” is a reference to the protagonist of Ubu Roi (1896), a satirical play by writer Alfred Jarry.

The figure that dominates Ernst’s painting bears some resemblance to a woodcut of Ubu Roi (1896) by Jarry, and its painted shadow looks like the tip of a pen, which may also allude to Jarry’s written play. Such references convey the fact that the concept of exchange is one of the chief principles of surrealism, both as an aesthetic trope—substituting one thing for another, as in portraying a spinning top instead of legs—and as a transnational movement. Surrealism fostered a productive network of artistic and intellectual exchanges that crossed mediums, disciplines, and geographical boundaries, from Europe to the United States, Latin America, and Asia.

In a similar vein, art exchanges between museums are not only about trading objects but also ideas about them. Substituting the Centre Pompidou’s Ernst for our Magritte motivates questions about varying surrealist practices, and it enables viewers to see our modern art holdings in a new light. Consider Ubu Imperator and the other Magritte painting in our collection, The Liberator (1947), which hangs next to it. Painted with nearly the same color palette of brick red, powdery sky blue, and earthy ochre hues, the two works are also strikingly similar in composition: a lone humanoid figure draped in fabric dominates the central foreground of both pictures; the faces of each are only partially visible, while their hands are emphasized. Made over two decades apart, these two paintings open our eyes to both correspondences and differences between two pioneering surrealist artists.

At the very heart of LACMA’s mission is to make the greatest examples of a wide range of art accessible to an equally wide array of audiences, and participating in exchanges such as this one is a collaborative and enlightening way to meet this goal. Lending The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe) to the Centre Pompidou gives visitors to the Paris museum a chance they may not have otherwise to see Magritte’s legendary painting. Likewise, being able to show Ubu Imperator in its place in Los Angeles grants museum-goers here the rare opportunity to see Ernst’s work, which is especially exciting given that no museum collection in Southern California includes paintings by the artist.

Ernst’s Ubu Imperator will be on view until February 2017. Stop by to see it while it’s still in L.A.!