Moving through the galleries of Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters, visitors are struck by a constant stream of sound. Sometimes subtle noises, floating over your head; low notes and rumblings, knotting your stomach. Then soothing tones, easing your nerves. The sounds grow louder and louder until there is a crash somewhere off to your left. Then the cry of a woman, to your right, cut immediately short. It's startling and slightly unnerving: was that real?

An airplane engine, an exorcism, the moan of an unidentifiable creature, gears, and clockwork—and these are just the things that are clearly audible; a series of frequencies, playing at an almost subconscious level, toys with your emotions. This balanced cacophony of sound tells a unique story, one which fits perfectly within the world of Guillermo del Toro, but was crafted by another maestro: Gustavo Santaolalla.

Born in Argentina, Santaolalla’s musical output is staggering: a pioneer of Argentinian rock and roll, a defining voice in the alternative scene of Latin America, and a two-time Academy Award-winning composer. Santaolalla has built a career out of blending traditional musical styles and has established a global network of collaborators such as Trent Reznor and Eric Clapton. Of course, in our interview, we cover these topics, but what he really wants you to know is that 18.98 is the frequency most closely connected with ghosts and that 528 is a frequency that has regenerative, healing capabilities. So we talked about that as well.

Could you talk a little bit about your beginnings as a musician? What was the music you surrounded yourself with when you were young and how did you find your voice?

I started playing guitar when I was five years old. But by the time I was 10, my teacher quit on me; I became self-taught from then on. By 16, I signed my first record deal with RCA with my band Arco Iris. We were the first Argentinian group to mix folk music from Latin America with rock and roll. We were very popular, but because of the constant military regimes in Argentina, we were ultimately blacklisted and didn’t get any airplay. From 15 to 24 years old, I went to jail many times. Not for any particular reason other than having long hair and playing in a rock band. I didn't do drugs, didn't belong to any political party; I was just playing in a band. That was enough reason to put you in jail for 24 or 48 hours. I came to the United States in 1978.

I came back to Argentina in the 1980s and did a fabulous project called De Ushuaia a La Quiaca. I traveled from Tierra del Fuego, close to Antarctica, to the limit with Bolivia, recording and taping rural musician from all over Argentina, playing the different styles that you get with the different geographic areas. That's where I met my wife. She was the photographer on that trip. Because I was the producer of the project, it gave me the possibility to work with many artists and musicians. They were not musicians or artists because they wanted to be on TV or radio. They just did it because it was their life, these people in the countryside.

My career as an artist and as a producer started simultaneously: I was always very interested in the art of making records, not only in the songs and the songwriting, but also the art of recording. By the time I started making records, there wasn't an alternative music producer in Argentina. I don't even think the word "alternative" was coined. But I knew what I wanted. I was interested in the concept of identity—what I did, who I am, where do I come from? It's always been something very important to me, not only for my art but also with the artists that I work with and produce. This concept applies to music and my work in cinema. I truly believe in the importance of finding your voice.

How did you end up working on soundtracks and composing scores for film and television?

I had a love affair with an instrument called the ronroco, which I've played since I was very young. It is like a brother to the charango, (a small stringed instrument originally from the Andes). But I play ronroco differently than it is usually played. Encouraged by great charango player, Jaime Torres, I made a record, called Ronroco (1998), gathering recordings from 13 years of my life with that instrument. I didn't have time to promote or play the album, but the record started to get a lot of attention. KCRW played it a lot.

One day I get a call from the director Michael Mann's office. He wanted to use a piece from that album for his film The Insider (1999). When I met with Michael, he played me the cue; it was a turning point in the movie, and it worked great.

Parallel to this, a friend contacted me and told me, “There's this guy in Mexico, it's his first film and you have to make music for this movie—his name is Alejandro Gonzalez Iñarritu. I almost didn't do it because I was so busy, then in the middle of the night, I started to think, what if this guy's a genius? What if this is a fantastic movie? So I called him in the morning, and I told them that if they come over to Los Angeles and they show me the movie I will consider it. Sure enough, they came here with Amores Perros (2000) and we watched the first 10 minutes, and I thought: I'm doing this!

Then, while working with Iñarritu, he says, "There's this Brazilian friend of mine, Walter Salles, he's doing this movie about Che Guevara. He's an Argentinian; you're an Argentinian. You should meet with Walter. So there I was, doing Motorcycle Diaries (2004). When we were presenting that film at Sundance, somebody said, "You know, you should meet with Ang Lee." It was no logistics, no strategy, no Hollywood agent. It was just like I'm telling you. One thing led to the other one. Suddenly I was doing Brokeback Mountain (2005). Then I was getting my first BAFTA for Motorcycle Diaries, then a Golden Globe, an Oscar; it just happened.

How did you meet Guillermo del Toro?

I've been a fan of Guillermo’s for years, but I met him at my first Oscars. Pan's Labyrinth (2006) had a few nominations that year and won several. He's such a great guy. There was always this idea of: "We should do something together sometime." I said, "Listen, man, I've always wanted to write a musical, but I always thought I needed a great story. When I saw Pan's Labyrinth, I thought, gee, this could be a dark musical.” I didn't know what he was going to say. But he said, "Man, we've been trying to make Pan's into a musical for many years!!! You will be perfect." That was it. We got together again and started to talk about lyricists. He said, "I like really good lyrics. I love Randy Newman, Joni Mitchell, Elvis Costello." Then he said, "What about Paul Williams?" and I immediately remembered his film Phantom of the Paradise (1974). I love Paul Williams!

So I met with Paul and immediately, we worked together on the movie Book of Life. They needed a few songs. I said, "This is perfect. Let's see how this works, if this team works." Sure enough, we wrote two beautiful songs. So that's how I arrived at this.

In Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters, you created a soundscape, which implements a system of sounds effects and tones, which emotionally affect and engage visitors. How did you formulate this system?

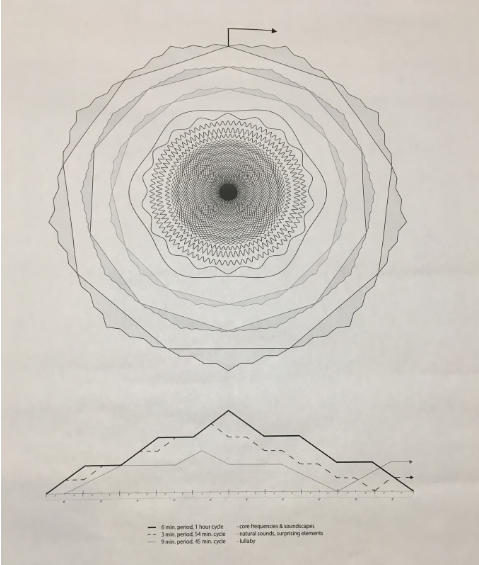

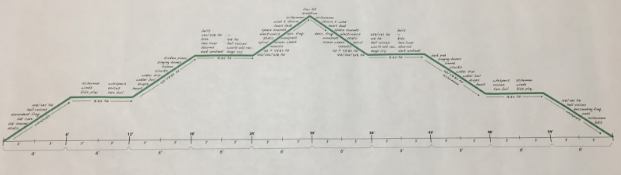

I thought, well, I have an hour, so I divided it into sections. Then, a crescendo, a rise and a fall over the whole hour, which works as a mirror. The sounds that you get at the beginning are paralleled, with variations. Another thing that I was very interested was in the use of frequencies and how frequencies affect us. All frequencies have an impact on us. Everything has a frequency; everything is frequencies. I looked at alternative and sacred scales. One which I used, is a scale that is important to Gregorian chant.

Working with (sound engineer) Anibal Kerpel, we used this other frequency that is a fantastic: 528. It is a frequency that has a healing factor. It regenerates DNA. And we used one frequency that is amazing that is 18.98, which is a frequency associated with ghosts. I also wanted to use low frequencies for their effect, they are very physical. You can feel it in your tummy. We wanted to have an underlying almost uncomfortable thing. I wanted to try to see if we could create something that had almost like a uterine bile—something that could be dark, almost human, but warm. I always remember I had a memory of being in a gondola in Venice at midnight coming from deep inside of a canal when everything is closed.

The whole loop, when all of the separate parts rejoin and restart, is nine hours. It takes nine hours for them to unite. Each sound and each frequency have their own path, which is different. But every nine hours they rejoin and they start exactly at the same point. Then, every nine minutes, there is the lullaby theme from Pan’s Labyrinth (composed by Javier Navarrete), which is a trademark of del Toro. I didn’t write it, but I love it! So every nine minutes there's that lullaby in different situations: a broken piano, a violin, toy piano.

Where did you find these sounds? Are they original, created in the studio, or did you track them down?

We did serious research to find the right tones and effects; we got some extraordinary stuff. There is a recording of an exorcism; some fantastic sounds are recording in these dunes in the Sahara in Africa. Dunes that produce sounds like voices. There are many different elements included in the soundscape. Actually, I have the voice of my granddaughter in there!

You also composed a short musical montage for our installation of Santi from Devil’s Backbone, which is like a radio switching stations through time. Where did this idea come from?

I came up with the idea of having a radio next to Santi, playing music that reflects the Spanish Civil War [when the movie takes place]. In those moments of war, radio became such an important tool for listening to what is happening. So I thought about sounds coming out of this radio, but also planes overhead. Obviously, it's a moment of the Spanish revolution, so I started with a little bit of somebody speaking in German to reference a connection with Nazi Europe. But then we included pieces of a Spanish Revolutionary poem and a tango too. The radio piece, in particular, was a lot of fun.

Experience Gustavo Santaolalla’s soundscape in Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters, which closes on Sunday! Buy your tickets now.