From Berlin, Amsterdam, and London to the New Bauhaus in Chicago

László Moholy-Nagy was a pioneering painter, photographer, sculptor, designer, and filmmaker as well as a prolific writer and an influential teacher in both Germany and the United States. Among his innovations were experiments with cameraless photography; the use of industrial materials in painting and sculpture; research with light, transparency, and movement; work at the forefront of abstraction; fluidity in moving between the fine and applied arts; and the conception of creative production as a multimedia endeavor. Radical for the time, these are all now firmly part of contemporary art practice.

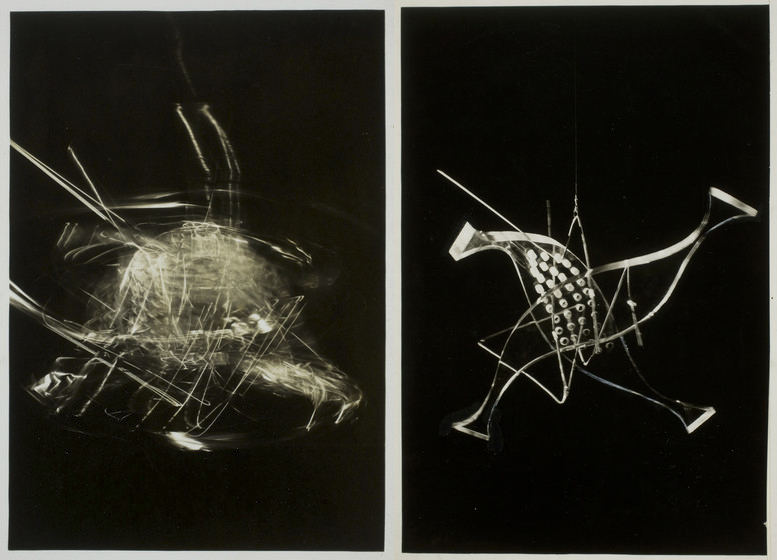

In Berlin, after his departure from the Bauhaus in 1928, Moholy’s commercial practice expanded while his artistic prominence in the avant-garde persisted unabated. In the coming years he continued to bring new industrial materials into his painting practice, while his experiments with what he called the “new vision” led to his 35 mm films documenting life in the modern city, his early involvement with color photography for advertising, and his remarkable kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage of 1930. Moholy made numerous black-and-white photographs of it along with the brilliant abstract film Lightplay: Black-White-Gray. He also was involved with stage and exhibition design, conceiving his Room of the Present to showcase endlessly reproducible photographs, films, posters, and examples of industrial design. Never realized during his lifetime, the Room was finally constructed in 2009 based on Moholy’s drawings and correspondence.

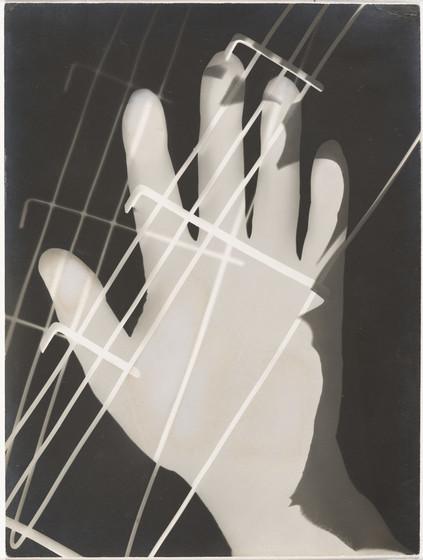

Photography was of special significance for Moholy, who believed that “a knowledge of photography is just as important as that of the alphabet. The illiterates of the future will be ignorant of the use of the camera and pen alike.” In the 1920s he and Lucia Schulz, his first wife, were among the earliest artists to make photograms by placing objects—including coins, light bulbs, flowers, even his own face and hands—directly onto the surface of light-sensitive paper. Moholy described the resulting images, simultaneously identifiable and elusive, as “a bridge leading to a new visual creation for which canvas, paintbrush, and pigment cannot serve.” His photomontages similarly combine assorted elements, typically newspaper and magazine clippings, resulting in what he called a “compressed interpenetration of visual and verbal wit; weird combinations of the most realistic, imitative means which pass into imaginary spheres.”

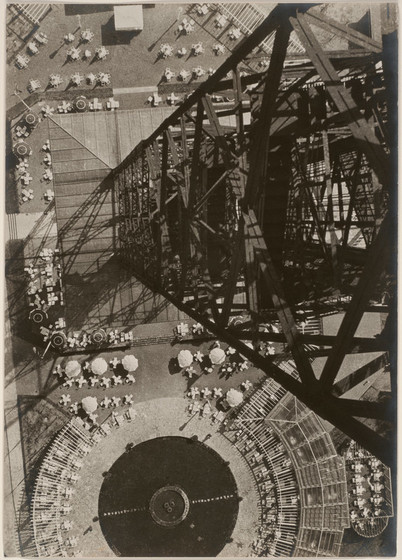

Moholy also made photographs using a traditional camera, often employing exaggerated angles and plunging perspectives to capture contemporary technological marvels as well as the post-Victorian freedom of the human body in the modern world. These photographs are documentary as well as observations of texture, captured in fine gradations of light and shadow. Moholy’s insights into photography’s relationship to society reached an international audience through his participation—as both co-curator and exhibitor—in the landmark exhibition Film und Foto, which traveled across Europe and to Japan from 1929 to 1931. Fifo, as it was called, was emblematic of Moholy’s “new vision,” in which unusual methods and techniques were hailed as a new means of creating art in an increasingly technological world. This understanding of art and art-making continues to resonate in the works of a wide variety of contemporary artists including Doug Aitken, Walead Beshty, and Barbara Kasten.

Forced by the rise of Nazism to leave Germany, in 1934 Moholy moved with his family to Amsterdam, where he continued to work in exhibition design and advertising and to collaborate on art and architecture projects. Within a year of arriving in Holland the family was forced to move again, this time to London. Moholy’s employment there centered around graphic design, including prominent advertising campaigns for the London Underground, Imperial Airways, and Isokon furniture. He also received commissions for a number of short, documentary-influenced films while in England.

In 1937 Moholy accepted the invitation (arranged through his former Bauhaus colleague Walter Gropius) of the Association of Arts and Industries to found a design school in Chicago, which he called the New Bauhaus: American School of Design. Financial difficulties led to its closure the following year, but Moholy reopened it in 1939 as the School of Design (subsequently the Institute of Design, today part of the Illinois Institute of Technology). Moholy transmitted his populist ethos to the students, asking that they “see themselves as designers and craftsmen who will make a living by furnishing the community with new ideas and useful products.”

In Chicago, despite working full-time as an educator and administrator, Moholy continued his artistic pursuits. His interest in light and shadow found a new outlet in Plexiglas hybrids of painting and sculpture, which he often called Space Modulators and intended as “vehicles for choreographed luminosity.” His paintings increasingly involved biomorphic forms and, while still abstract, were given explicitly autobiographical or narrative titles—the Nuclear paintings allude to the horror of the atomic bomb, while the Leuk paintings refer to the cancer that would take his life in 1946.

Moholy’s goal throughout his life was to integrate art, technology, and education for the betterment of humanity. “To meet the manifold requirements of this age with a definite program of human values, there must come a new mentality,” he wrote in Vision in Motion, published posthumously in 1947. “The common denominator is the fundamental acknowledgment of human needs; the task is to recognize the moral obligation in satisfying these needs, and the aim is to produce for human needs, not for profit.”

Part 1 of this blog post, “Early Work and the Bauhaus Years,” appeared on Unframed yesterday, February 8.

View Moholy’s works in LACMA’s Moholy-Nagy: Future Present from February 12 through June 18, 2017. The first comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s work to be seen in the United States in nearly 50 years, the exhibition includes approximately 300 works, some never before shown publicly. Member Previews are February 9–11.