Early Work and the Bauhaus Years

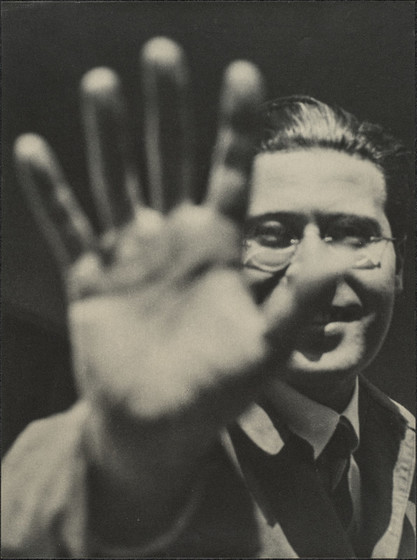

Instagram. Twitter. Snapchat. Facebook. Tumblr. Pinterest. László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946), an artist and educator who strove to make images and ideas accessible to the broadest possible public, would no doubt take great advantage of all these platforms were he alive today. One of the most versatile figures of the twentieth-century avant-garde, he was a brilliant and restless experimenter who ardently believed in the potential of art as a vehicle for social transformation and in the value of new technologies in harnessing that potential.

Born in rural Hungary in 1895, Moholy lived and worked, over the course of his career, in Budapest, Vienna, and Berlin; at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau; and in Amsterdam, London, and Chicago. A desire to expand his artistic horizons led to his early geographic relocations, while his later moves were the result of the rise of Hitler and National Socialism in the 1930s. Moholy’s work was collected and exhibited internationally during his lifetime, and his writings, often pedagogical, were widely published and translated.

Moholy initially pursued law studies at the University of Budapest but left after two years, in 1915, to serve as an artillery officer in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. He began drawing while on the war front, depicting its bruised landscapes and devastated figures. Wounded in 1917, he convalesced in Budapest, writing for the city’s avant-garde publications. Moholy remained there after his discharge in 1918 to focus on painting, and was soon drawn to the cutting-edge art movements of the period, including Cubism and Futurism. Moholy moved to Vienna in 1919 before settling in Berlin in 1920, where he served as a correspondent for the progressive Hungarian magazine MA.

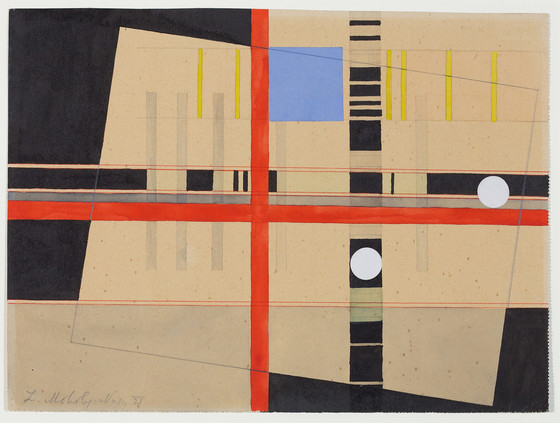

The letters and glyphs of Dada informed Moholy’s visual art around 1920 while the hard-edged geometries and utopian goals of Russian Constructivism influenced his initial forays into abstraction shortly thereafter, particularly works that explore the interaction among colored planes, diagonals, circles, and other geometric forms. By the early 1920s Moholy had gained a reputation as an innovative artist and perceptive theorist through exhibitions at Berlin’s radical Galerie Der Sturm as well as his writings. “Production-Reproduction” (published in 1922), for example, illuminates the notion of iteration and reiteration in various media as a means to “produce new, as yet unfamiliar relationships.”

Moholy described his geometric abstractions as a “glass architecture” of simple, minimal forms, embodying light and transparency and intended to manifest a utopian society. In his attempt to envision the new, Moholy increasingly worked with industrial materials including metals and plastics. Going one step further, Moholy’s 1923 “telephone paintings” were not made by his own hand but rather fabricated by an industrial manufacturer; Moholy thereby set a precedent for later generations of artists from John Baldessari to Jeff Koons.

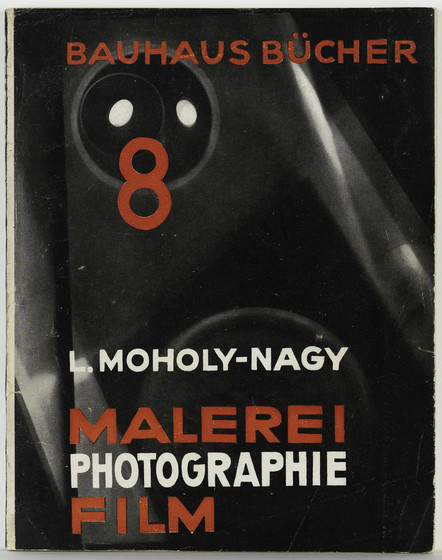

In 1923, Moholy began teaching at the Bauhaus, an avant-garde school that sought to integrate the fine and applied arts, where his colleagues included Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and other pathbreaking modernists. Architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, invited Moholy to expand its progressive curriculum, particularly by incorporating contemporary technology into artistic practice. Moholy directed the metal workshop and, with Josef Albers, taught the school’s foundation course. He also had a part in Bauhaus graphic design achievements, collaborating with Herbert Bayer on stationery, announcements, and advertising materials.

With Gropius, Moholy published the Bauhaus Books series, conceived to give voice to leading artists of the day. The eighth book in the series was Moholy’s Painting Photography Film (1925), a widely disseminated treatise on the critical role of photography and what Moholy called “the use of light as a creative agent.” The fourteenth and final volume was also by Moholy, From Material to Architecture (1929), published a year after his resignation from the Bauhaus (along with other faculty) due to internal disagreements over the school’s focus.

After leaving the Bauhaus, Moholy turned to commercial and theatrical design work as his primary means of income to support his family with his second wife, the writer Sibyl Pietzsch, with whom he would have two daughters. Through advertising as well as book, exhibition, and theater design his ideas reached a broad audience in the 1930s. This work was frequently collaborative and interdisciplinary by its very nature and followed from Moholy’s dictum “New creative experiments are an enduring necessity.”

Part 2 of this blog post, “From Berlin, Amsterdam, and London to the New Bauhaus in Chicago,” will appear on Unframed tomorrow, February 9.

View Moholy’s works, including Room of the Present, in LACMA’s Moholy-Nagy: Future Present from February 12 through June 18, 2017. The first comprehensive retrospective of the artist’s work to be seen in the United States in nearly 50 years, the exhibition includes approximately 300 works, some never before shown publicly. Member Previews are February 9–11.