The exhibition Light Play: Experiments in Photography, 1970 to the Present, a complementary show to Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, is on view Saturdays and Sundays through June 18, 2017, at LACMA’s Study Center for Photographs and Works on Paper. Included in Light Play are several works by Los Angeles-based artist Susan Rankaitis. Carol S. Eliel, curator of modern art at LACMA (and co-organizer of the Moholy retrospective), sat down with Rankaitis to talk about the artist’s several decades of making multimedia work involving photographic and painting processes as well as scientific research and methods.

Carol Eliel: Your works are hybrids of painting and photography. Tell us about your process.

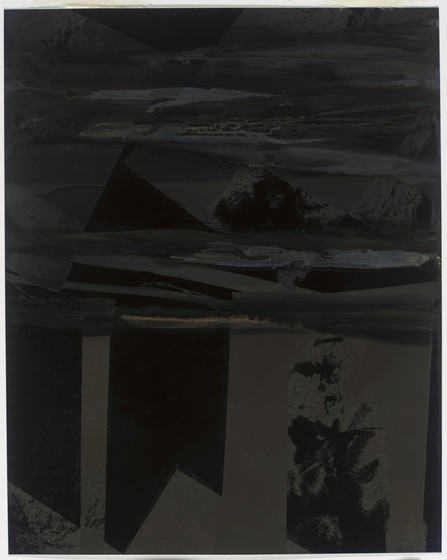

Susan Rankaitis: My work is about thinking deeply about life and science and the world around us. All of my work is hand-made. It goes through so many wet processes—it’s partially fixed, and then I’ll do something else with light, and then a little bit more with developer here and there. I’ve just tried to figure out how I could structure image/non-image in different ways.

So what processes do you use, how do they accrete?

Every single piece is different, but usually it would be trying to get a partial photographic image on—maybe with an enlarger, oftentimes using masking in different parts, doing burning and dodging for different parts, and then really working with the paper in the developer. I’ll use resin-coated paper, because it’s a tough paper—I can’t get that surface any other way. I’ve done a lot of erasure. In other words, I negate, cover up, disguise a lot of different parts. And one of the things that I’ve always done is worked around images; most of my images can be seen in any orientation. There is the painting, really fluid . . . using the developer like paint but also simultaneously using light, little flashlights and things like that.

And you started out as a painter, prior to taking up photography?

When I came out from Illinois for graduate school at USC, my paintings were large-scale, abstract, really brightly colored. Being in Los Angeles first shattered, and then rocked, my world. I had to respond to everything I was seeing around me—the quality of light, the landscape, the airplanes overhead, everything. It changed me so much. Somehow something became possible. Near the end of my first year of graduate school, I figured out I had to totally redefine painting for myself, that I didn’t want to paint on canvas. I don’t know if I used the term “interdisciplinary”—I don’t know how much it existed at that time—but I remember talking about “linkages.” My thesis title was “The Linkages of Painting and Photography,” and so that’s what I was trying to do. Soon after, linking became that place of absolute hovering right between the two—both but not either.

Soon after you came to L.A. in the mid-seventies, you met Barbara Kasten, another artist whose work is featured in Light Play.

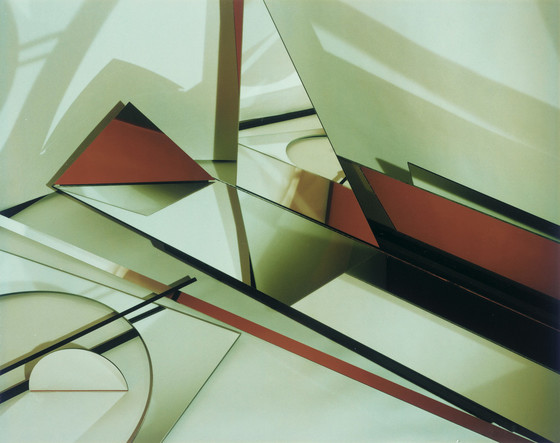

Barbara was so incredibly helpful to me at the beginning of my career in Los Angeles. She had a studio really near ours in Inglewood. After a fire at the studio, Barbara gave me some of her old clothes—which, if you know Barbara, she has beautiful clothes—because I’d lost all that. We were both into what could be called the experimental, abstract end of photography. But she comes out of weaving, and I view her work as extremely constructed. My work has embedded structures, and structural fluidity. What’s really interesting is—when thinking about her work and thinking about my work and what we did at the time—we were looking at entirely different facets of what Moholy-Nagy did. He was that good, he was that wide-ranging. There is so much in the work, and we all take from things what we need.

Tell us about how you first got to know Moholy-Nagy’s work.

I think it was 1976, around the time that my husband, [photographer] Robbert Flick, had an exhibition of his work at The Art Institute of Chicago. He went to meet with the curator David Travis, and introduced me to him. I showed him some of my paintings in slide form and he said, “I have something to show you.” He pulled the photograms of Moholy-Nagy out of the vault. And what amazed me was, it was absolutely what I was interested in. This incredible surface that almost seemed like it moved; that no matter what light you looked at it in, it would slightly shift. It just hit me on such an incredibly visceral level. It was like looking at a little Sienese painting, with that gold on it, and every time you would look it would be slightly different. I remember him pulling them out of the vault and it just kind of gave me this path. To me they were totally on the cusp between painting and photography. They were the most painterly photographs I had ever seen. They were melded in such a way that I saw it could really be done. At that point in time there were things in existence like hand-colored photographs, but I was not interested in them in the slightest. I really wanted, for lack of a better term, a pure hybrid that was of painting and yet was photographic.

What other artists would you relate your work to?

The Song dynasty painters. Who were not just artists but who were calligraphers, they were poets, they were involved in the politics. I feel like as much as I want my work to be hybridized and interdisciplinary, in a strange way I want my life to be like that too.

As a teacher you have a capacity to impart that notion, not only how to be an artist in the world but how to be a person in the world.

Right . . . and you should do whatever you’re curious about. All of my work for about the past ten years has been about neuroscience, and particularly about emotion, particularly fear.

You obviously really like the hard sciences, having collaborated with neuroscientists and serious scholars in such fields.

It appeals to me greatly, and it is the most humbling experience I have ever had. I am not a scientist. I do not purport to be a scientist; I do not purport to know science. I’m just so interested in it. I read it, I try to understand it. One of the reasons I like it is it’s just like art—there are no easy answers. It’s pretty open-ended, it’s pretty . . . on some levels, indeterminate. This is what is so great about being an artist now. If you can keep your head on straight, you can pretty much think about and do whatever you want to.

Light Play features works from LACMA’s permanent collection by Rankaitis as well as by Walead Beshty, Phil Chang, Robert Heinecken, John Houck, Masood Kamandy, Farrah Karapetian, Barbara Kasten, William Larson, Sheila Pinkel, Alison Rossiter, Wolfgang Tillmans, James Welling, and Jennifer West. Light Play is on view in LACMA’s Study Center for Photographs and Works on Paper, adjacent to Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, on weekends through June 18, 2017 (Saturday and Sunday, 10 am–7 pm).