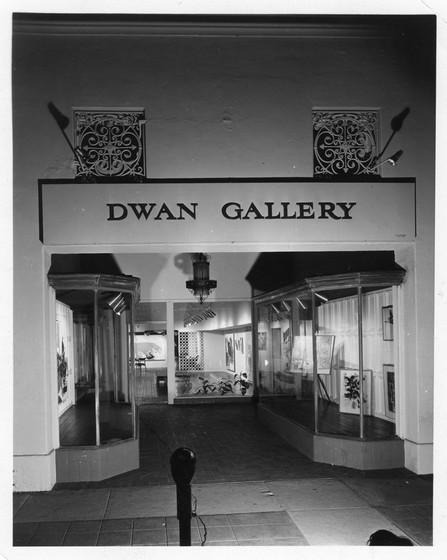

The opening of the first Dwan Gallery in October 1959 occurred during a revolution in transportation technology as profound in its effects as the invention of the electric trolley car, the automobile, and the propeller plane a half-century before. I refer to two innovations in particular. The creation of the interstate highway system by Congress and President Eisenhower in 1956 unleashed a frenzy of freeway construction lasting into the I970s. Among the most ambitious public works projects in the country’s history, the interstate linked the most distant locations in a grid of unary design and signage, dramatically quickening the pace of travel and transforming human relationships to distance and speed. The second of these innovations, the commercial jet, had a profound impact. Developed for military use during and after World War II, the jet propulsion engine had considerable advantages over the propeller kind. Less prone to failure, it reduced the drone of multiple propellers to a soothing white noise and reached speeds of up to six hundred miles per hour, cutting flying time almost in half: the journey between Los Angeles and New York that had previously taken nearly eight hours now took four and a half hours. The first transcontinental jet flight between these two coastal capitals, on American Airlines, departed on January 9, 1959, the winter before Virginia Dwan opened her gallery.

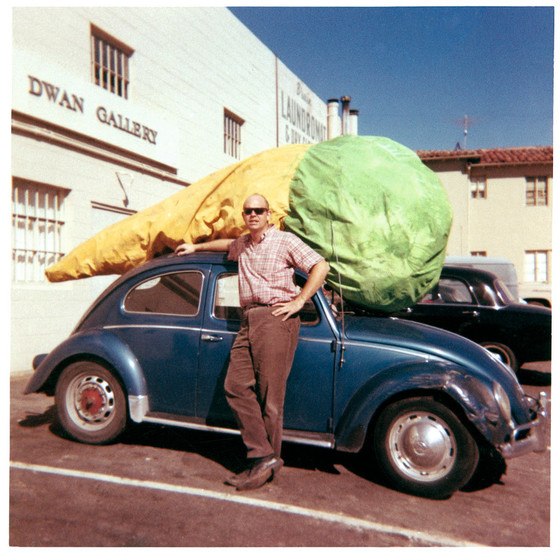

The “jet age,” they called it. As a result of jet service (and another invention, computerized ticketing) and aggressive advertising campaigns, the number of flyers grew by leaps and bounds from 1959 to 1970. Equally germane, the jet was as efficient in transporting goods as people; the volume of domestic and international airfreight greatly increased. With the opening of a vastly expanded Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) in 1961, the metropolis—home of the ultimate tourist destination (Disneyland), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech, and the aerospace industry—was itself a symbol of the new mobility, as expressed by the iconic Theme Building at the refurbished airport, a flying saucer-like structure suspended between crossed parabolas.

The impact of such innovations on the making and distribution of art cannot be overstated. Informal networks emerged, linking galleries in Los Angeles and New York. Artists and dealers traveled between the coasts with greater regularity. As the two art scenes came into regular contact, the alleged differences between East and West Coast style and “sensibility” were enunciated in reviews and articles summoning warmed-over stereotypes of place and lifestyle, often to the detriment of California work; even now this binary is rehearsed. The situation was far more fluid, as the history of the Dwan Gallery shows. Artists and artworks moved more swiftly than ever before between the coasts and Europe. Ideas, forms, and techniques were circulated and exchanged. Dwan was a central player in this process of “bicoastalization,” and hers was arguably the first bicoastal gallery, a common enough scenario now, altogether uncommon then.

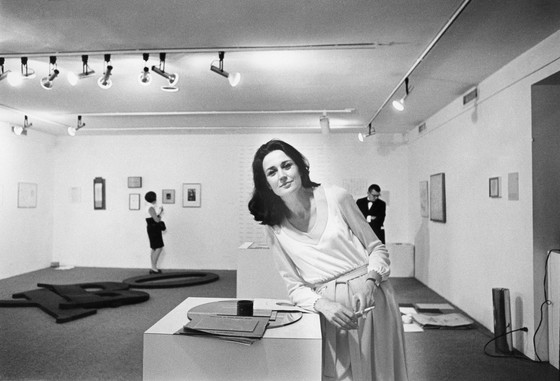

Importing works on consignment from galleries in New York and Paris, and eventually works by East Coast artists affiliated with her gallery to her Los Angeles space, Dwan facilitated dialogues across regional and national lines. Like the Castelli and Green Galleries in New York, Rive Droite and Sonnabend in Paris, and Konrad Fischer in Düsseldorf, Dwan existed in a strikingly different milieu at the origins of today’s global art industry. Even then, the example of Dwan was unique. It sets before us an image of unbounded creativity catalyzed by the gallerist’s largesse and curiosity—her openness to radical aesthetic departures disconnected from market imperatives. Possessing a private income, Dwan was able to offer monthly stipends to artists she believed in, and to sponsor projects of ambitious scale and cost.

The first business of Dwan’s operation was the cultivation of “ideas,” as she described these projects—ensuring that the works were made and put out into the world.1 Sales, sporadic at best, supported the artists and gallery. Sales mattered, but as a secondary concern. Dwan could adopt an idealistic point of view knowing that she would be able to “keep the doors open.” She could take risks that most of her peers could not. And she took them again and again. Dwan’s fearlessness set her apart, but her attitude is of its time; it speaks of the sixties and early seventies, a period of extreme aesthetic daring. That a gallery of such momentous importance ran at a loss during its entire existence could not seem more at odds with the profit-driven obsessions of our own moment.

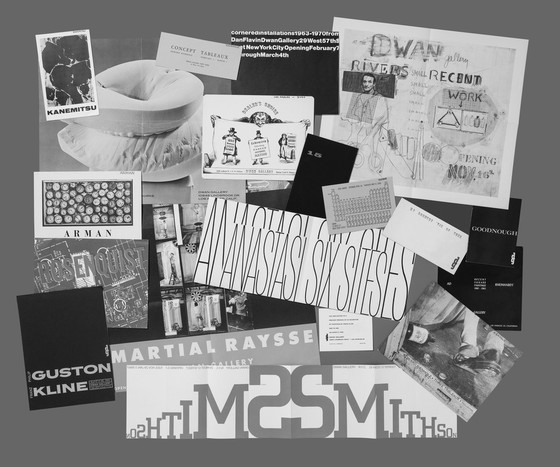

The contemporary art gallery is a relatively understudied subject. Dwan Gallery must be counted among the most paradigmatic of its time, but its brief history has yet to be examined in depth. Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971’s presentation of the gallery’s short but storied 11-year run is a case study of the art gallery as a form during this seminal era. Tracing a succession of tendencies that Dwan brought to visibility, it presents a narrative of vanguard art in the United States and France, highlighting a selection of the 134 exhibitions staged at the gallery between 1959 and 1971. But the Dwan story has still other dimensions. It moves from Los Angeles to New York and on to Paris, from New York to the American West; from art centers to obscure places; from displays of paintings and sculpture to environments and conceptual activities that unsettled definitions of medium and object. It concludes with sited and itinerant endeavors that exposed the conventions and perceptual limitations of the gallery frame. By the time Dwan closed her New York space in June 1971, the most adventuresome of her artists had brought the white cube—the pristine, “neutral” aesthetic container—to the brink of irrelevance. The path that led from abstract expressionism to assemblage and pop, from nouveau réalisme to minimalism, from language to land art; from Westwood to West 57th Street; from Los Angeles to Paris to New York; from the Pine Barrens and Yucatán to the Western desert—came to an end. Dwan was only 39 years old.

Her story is embedded in a particular moment of historical possibility, and is altogether unique. The surprising trajectory of Dwan’s operation—she begins with paintings and sculptures of domestic scale, moves to constructions that burst the gallery at its seams, retools for minimalist works of bodily scale and industrial facture and then for a linguistic art of “ideas” that takes up hardly any gallery space, and from there bounds to land-based projects—leads, as it were, to the dismantling of her enterprise.

Indeed, the relevance of the art gallery as aesthetic container is severely questioned in that astonishing period prior to the market’s rise during the 1980s with the return of traditional media and once-discarded formats of painterly gesture and figuration—the very “objects” that had formerly appeared (at least theoretically) on the verge of extinction. Dwan’s involvement with many of the most challenging practices of her time appears immensely generous. Dwan saw it differently. “I’m not really interested in generosity. But I’m interest in the ideas, and I take a great deal of pleasure in seeing the ideas brought out to other people.”2 Fostering ideas—difficult ideas—was worth it:

As art became increasingly self-contained and even remote, I stretched more and more toward it and found satisfaction in that engagement and communion. I had to be willing to risk the voyage to a place that does not easily reveal itself. One used to look at art. Today art reflects our image back upon us. That is what makes it so difficult.3

This essay was excerpted from the Dwan Gallery: Los Angeles to New York, 1959–1971 exhibition catalogue. The exhibition is on view through September 10, 2017 in the Resnick Pavilion.

1 Elayne Varian, “Interview with Virginia Dwan of the Dwan Gallery,” 1969, Exhibition Records of the Contemporary Wing of the Finch College Museum of Art, 1943–1975, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, unpaginated.

2 Varian, “Interview with Virginia Dwan of the Dwan Gallery,” unpaginated.

3 Virginia Dwan, “Writings,” in Dwan Gallery: Los Angeles to New York, 1959–1971 (Washington: National Gallery of Art; Chicago; London: in association with the University of Chicago Press, 2016), 280.