On the evening of June 21, 1941, the Russian artist Marc Chagall and his wife Bella arrived in New York, which they would soon make their new home. After the fall of France to German forces in 1940, the Jewish couple was no longer safe living in the Provençal village of Gordes and they were happy to receive the invitation of Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the help of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee to emigrate to the United States. Though Chagall was fascinated by the scale and pace of this new and unfamiliar city, which he described as a “Babylon,” he spoke very little English and struggled with painful feelings of homesickness. The Chagalls surrounded themselves with a group of Yiddish- and Russian-speaking expatriate artists and intellectuals, recreating a sense of the community they had left behind in Europe.

A year after settling into his new life in America, Chagall was given the chance to draw upon his memories of Russia through the production of Aleko, a ballet based on a poem by Alexander Pushkin and set to Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s Trio in A Minor. The story follows an aristocratic youth who joins a band of Romany travelers (formerly referred to as “gypsies”), falls in love with the chieftain’s daughter, and eventually murders her when she leaves him for another man.

This commission by the Ballet Theatre of New York (presently the American Ballet Theatre) marked Chagall’s first experience with creating theatrical designs for a ballet, though he had expressed a passionate interest in dance throughout his life, and especially since seeing Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes perform in Paris in the 1910s. Aleko’s choreographer, Léonide Massine, was a fellow Russian emigré and former Ballets Russes collaborator who worked for months alongside Chagall in his studio. The art critic Emily Genauer recalls visiting Chagall’s studio in the midst of preparations for Aleko, and coming upon the artist and Massine “lightly dancing about the studio [...] as together they worked out the color patterns for the new ballet.” The pair conceived of the choreography, scenario, and theatrical design while listening to the sound of Tchaikovsky’s music and Bella’s voice as she read verses of the poem aloud.

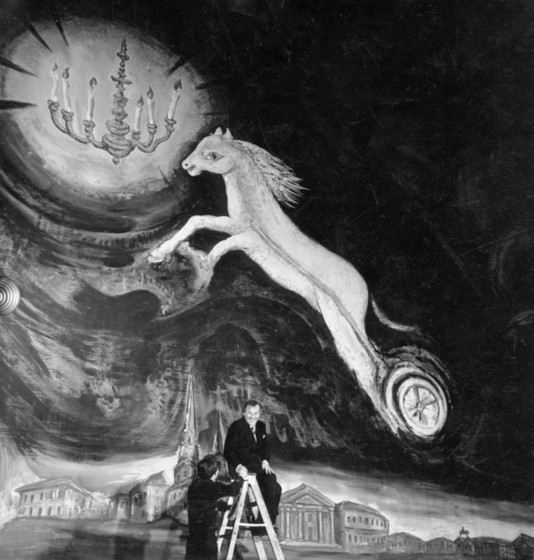

Aleko was scheduled to premiere at the Metropolitan Opera House, but New York’s strict union restrictions barred Chagall from painting the backdrops himself. This, coupled with the high costs of producing the Ballet Theatre’s season in New York, caused the fledgling company to relocate to Mexico City, where they began a residency at the Palacio de Bellas Artes as guests of the Mexican government. Marc and Bella crossed the border into Mexico on August 2, 1942, following a difficult passage through customs, where the artist’s sketches were heavily scrutinized and he was forced to erase all the notes he had written in Russian. Work on the ballet began a mere two days later.

The company and production team were composed of a diverse group of emigrés and refugees from Russia, England, and the United States, along with hundreds of local Mexican artisans. Chagall formed a particularly close bond with British ballerina Alicia Markova, a fellow Jew and former dancer with the Ballets Russes. She recalls in her memoirs that she would frequently accompany the artist to the market, where vendors peddled fabrics dyed in “almost psychedelic colors” and musicians played guitar. Massine also remarked upon the omnipresence of music throughout the city and was impressed with the local folk dances, especially one called jaki, where dancers imitate animals. Interestingly, Aleko would include a large number of fantastical animal characters, who appear dancing wildly during a nightmare scene.

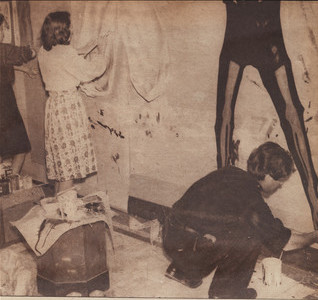

The ballet was set to premiere on September 8, so Chagall had only a little over a month to complete four monumental backdrops and 64 costumes. Bella took charge of the costume shop, and both she and Chagall worked alongside a large team of local seamstresses, technicians, and artisans, which included the surrealist painters Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Esteban Frances. Even with this additional assistance, Chagall attended to every detail and designed many of the costumes with a specific dancer in mind, as evidenced by the notes he made on his preparatory sketches where he even sometimes dictated hairstyles and makeup. In a 1942 interview in Hoy magazine, Chagall acknowledged: "In ballet it is good to do everything for yourself, because any detail is decisive. For example, we must take into account [...] that the stage light does not really illuminate the costumes: [they] have to have their own light, and you have to know how to 'paint it.'"

The ballet’s opening performance was an enormous success; Bella counted 18 curtain calls and the audience chanted Chagall’s name until he joined the cast onstage. “Chagall’s decorations are burning like the sun in heaven,” Bella wrote to Opatoshu, shortly after the premiere. “And the whole ballet [...] spurts with light and joy.” After the opening performance, Marc and Bella spent a brief two weeks in Mexico before returning to New York, where the ballet premiered to great acclaim at the Metropolitan Opera a month later. Though Chagall was not in Mexico for long, the country left a deep impression on the artist, and upon returning to America he completed a series of gouaches directly inspired by his experience in Mexico, which featured guitar players, dancers in sombreros, and women in traditional Mexican dress.

Aleko remained in the Ballet Theatre’s repertory until the backdrops were sold at auction in 1977, during a period when the company was struggling financially. The costumes were not seen again until 1991, when they were exhibited at the Centro Cultural de Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico, which invited Martha Hellion to serve as a curatorial consultant and inspect the costumes. She found them in a very poor state, and conducted extensive archival research to restore each costume to exhibition condition. Today, the costumes, which are owned by the Chagall estate, are still overseen by Hellion, who collaborated closely with LACMA’s curatorial team on their presentation in Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage.

The experience of working on Aleko brought Chagall into contact with a highly diverse group of creative professionals of different cultural, religious, and artistic backgrounds. Though the artist’s influences were many, his fascination with the folk art of his homeland and Mexico is particularly visible in his designs for this ballet. Chagall’s sketches and costumes for Aleko remain vibrant, and tell the story of an artist who strived to create a visual universe replete with elements drawn from different cultures as well as fantasy and dreams.

Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage is on view through January 7, 2018.