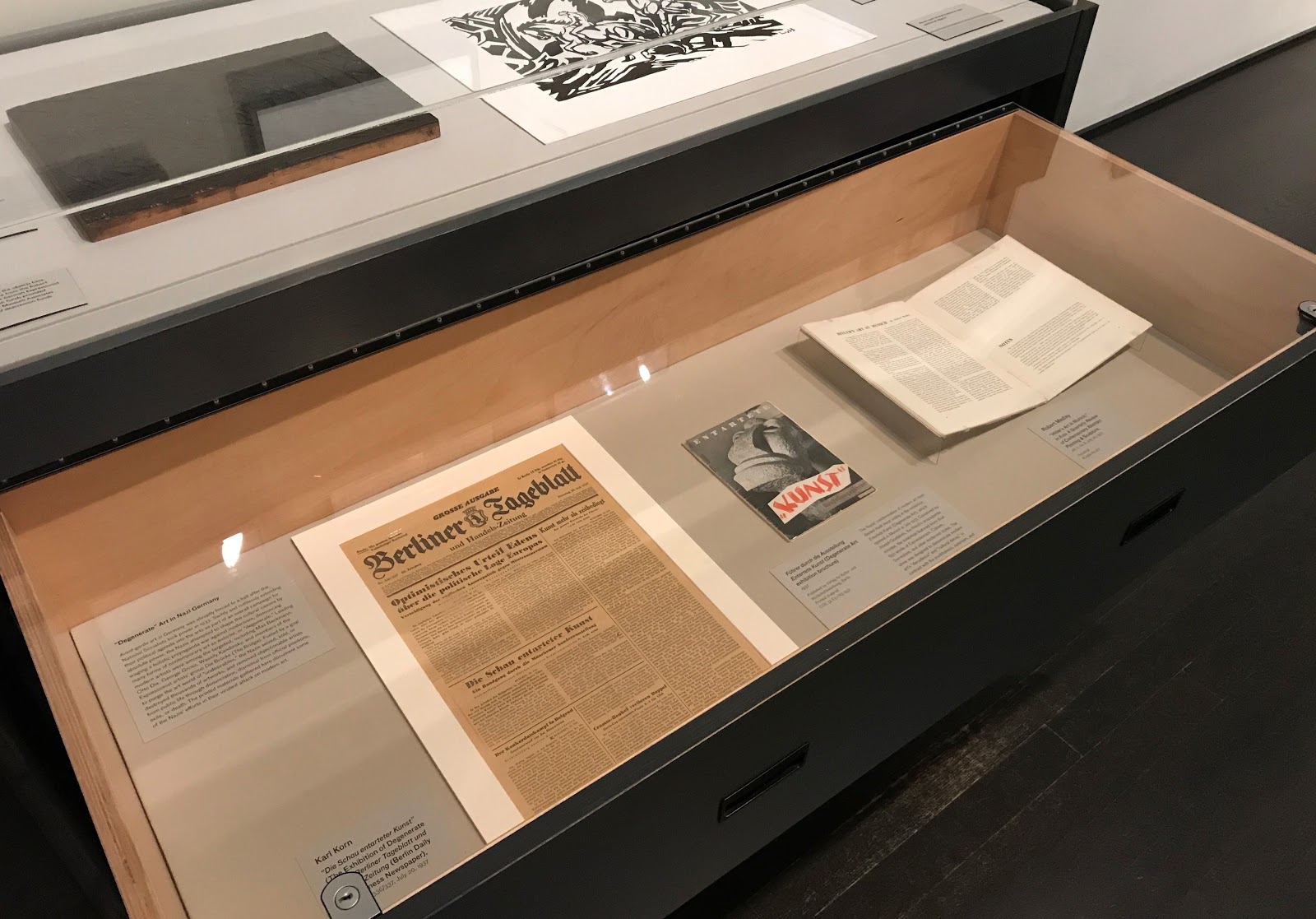

The 20th century saw a vast proliferation of paper-based media in the form of books, periodicals, and printed ephemera, which became naturally positioned as primary vehicles for communication and artistic expression throughout the flowering of avant-garde art in Europe. Today, these materials enrich our understanding in relation to the creation, circulation, and critical reception of modern art, helping us to obtain a multifaceted view of its development and impact. The Rifkind Center’s collection of books, journals, and portfolios reflects the rich activity of the German Expressionists and their avant-garde affinities across Europe. A selection of these materials is displayed on a rotating basis in the pull-out drawers located in the Modern Art galleries, offering an addendum to the vibrant display of paintings and sculptures from the permanent collection, as well as to the rotating exhibitions of the Rifkind collection in the adjacent gallery.

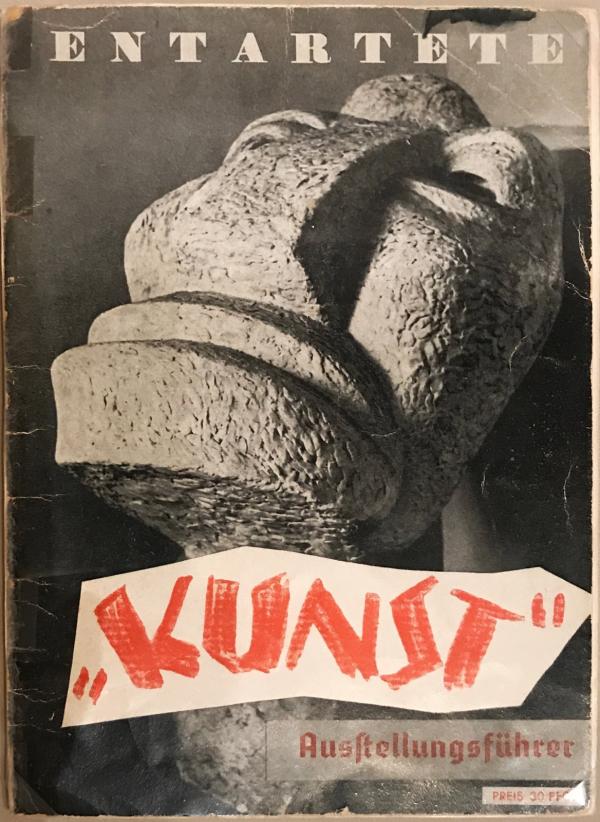

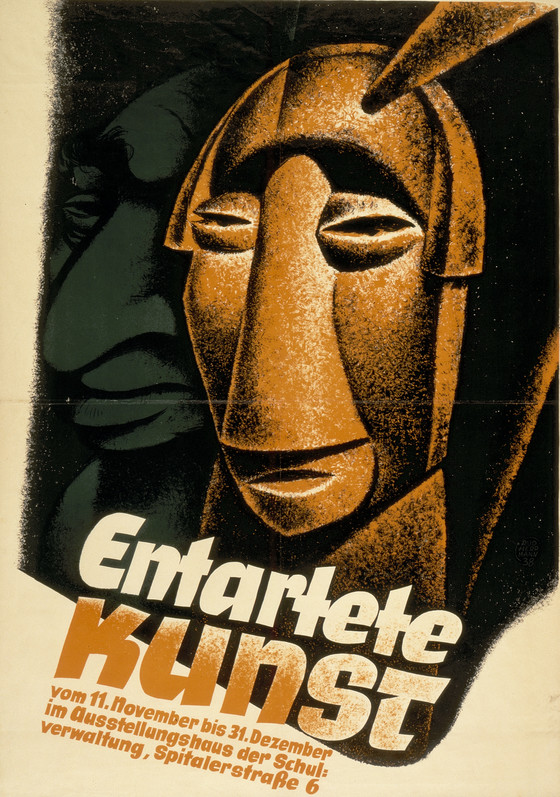

Currently on view is a selection of published materials that focus on the tumultuous fate of modern art during Adolf Hitler’s power in Germany. Pages from a newspaper, exhibition catalogues, and books present examples of how the Nazis used published media as an essential propaganda organ, denouncing artworks in Expressionist, Cubist, Surrealist, and other abstract or modern styles as exemplifications of moral decadence and cultural decay.

Leading artists of the German modernist movement were collectively scapegoated for social challenges or singled out and positioned as enemies of the Nazi state. Among those targeted were Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Ernst Barlach, Max Ernst, George Grosz, Käthe Kollwitz, Emil Nolde, and members of Expressionist artists’ groups Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). With the goal of purging the art world of “undesirables,” the Nazis sold or destroyed thousands of artworks confiscated from museums, galleries, and private collections. Individuals considered objectionable were excoriated, dismissed from official positions, exiled, or murdered.

Hitler’s staunch exaction of social “purity” extended into art in the form of aesthetic standards that uniformly heralded youth, optimism, and triumphant heroism at the cost of the more nuanced, complex, and thought-provoking capacities of art. Hitler’s vision was encapsulated through an exhibition of officially approved art in the first Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (Great German Art Exhibition) at the House of German Art, sending an explicit message about the kind of society that he sought to build.

The most dramatic manifestation of Hitler’s disdain for modern art took the form of the 1937 exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). Following the opening of the House of German Art by one day, the exhibition was a deliberate antithesis to the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung. Conceived by Joseph Goebbels, the Reich’s propaganda minister, the exhibition was designed to be a scurrilous spectacle that shamed and castigated avant-garde artists by framing them through a lens of mental and moral corruption.

The Nazis’ denunciation of modern aesthetics extended not only to visual arts but to all aspects of culture, including literature, music, and film. During this period, not only artists but musicians, writers, critics, publishers, theater directors, and actors were placed under scrutiny through compulsory membership in the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Chamber of Culture). It controlled all professional practices in the arts and could issue decrees prohibiting artists from working.

The materials on display highlight the cross-section between art, politics, and published media during the most egregious attack on art in modern history. The impact of the Nazis’ cultural violations still reverberates today, particularly through recurring questions surrounding the provenance and repatriation of looted artworks. To learn more, you can revisit this past Unframed post or view this digitized catalogue of LACMA's 1991 exhibition Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany. Researchers can also make an appointment at the Rifkind Center to explore the work of artists who, despite the efforts of the Nazi regime, triumphed in marking the birth and expression of modernity.

This display is on view until May 20, 2018, in the Ahmanson Building, Level 2.