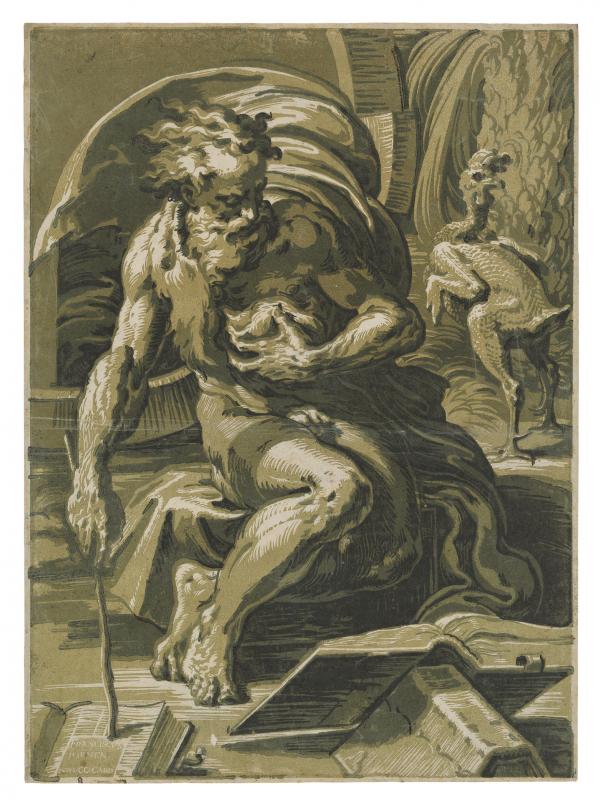

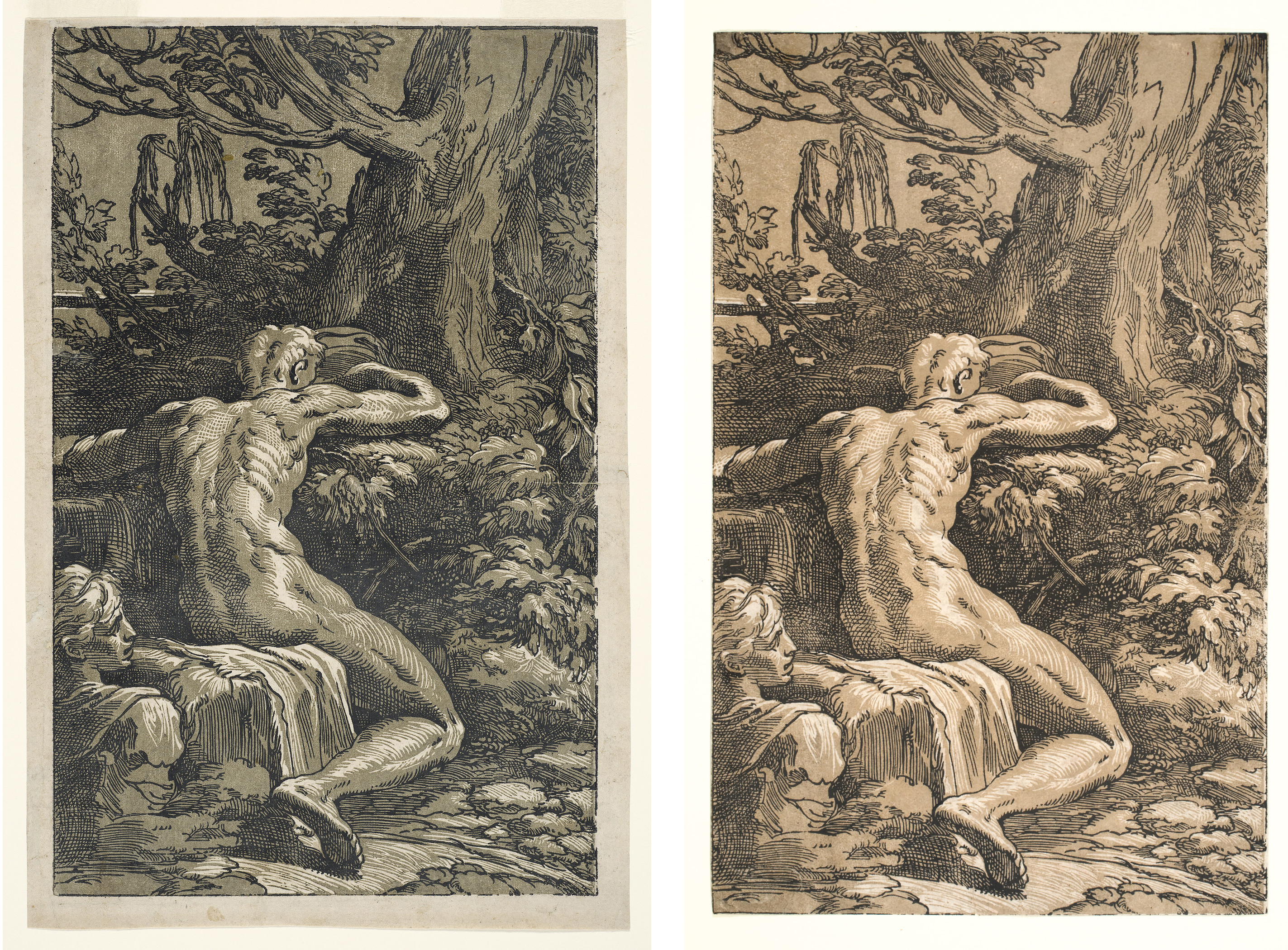

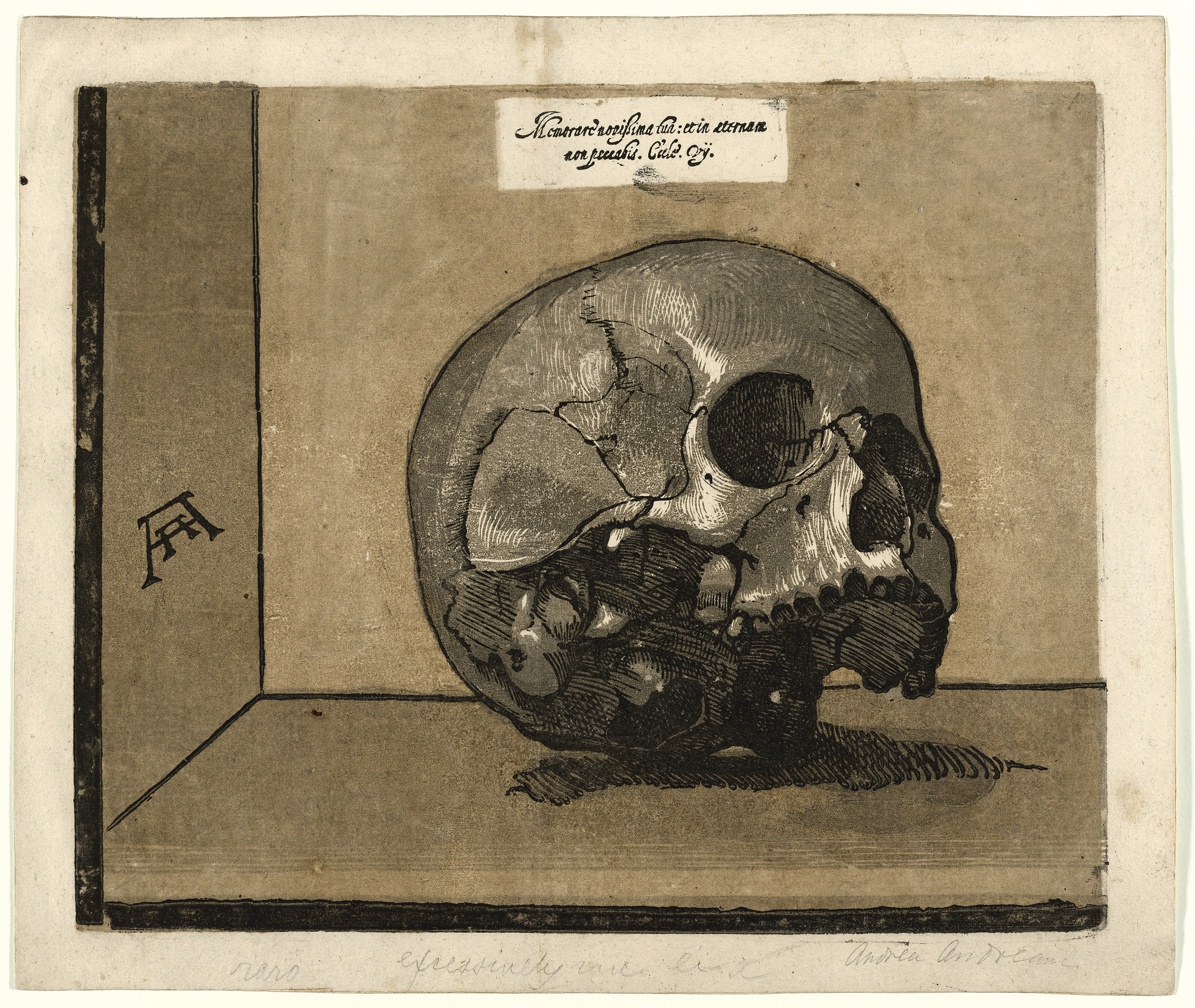

Studying Renaissance prints, I am continuously astonished by the survival of these delicate works of art on paper, more often than not in remarkably fine condition. This is particularly true in the case of chiaroscuro woodcuts, which are some of the rarest prints of the period. Introduced in Italy around 1516, chiaroscuro woodcuts represented a small, elite share of the print trade. Over the course of the 16th century, only around 200 chiaroscuro compositions were executed—and each was printed in limited numbers. These exquisite works, some the size of postcards, others matching the scale of paintings, were treasured from the time they were made, and have passed through the hands of one collector to the next across five centuries.

Today, Renaissance chiaroscuro woodcuts issued from Italian workshops have found their way into museum, library, and private collections around the world. In preparing the exhibition The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy over the past decade, I have had the great pleasure of visiting some 40 collections—primarily in the United States and Europe, and as far as Japan—to examine over 2,000 chiaroscuro woodcut impressions. Some of these collections date to the 16th century, while others were formed in recent decades. The wide dispersal of these beautiful works speaks to their broad and enduring appeal.

The chiaroscuro woodcut was one of the earliest successful color printing techniques in Europe. Despite the high esteem with which artists, collectors, and scholars since the Renaissance have regarded the technique, it has remained one of the least understood of early printmaking. Notably, much confusion around the attribution and chronology of Italian chiaroscuro woodcuts has persisted, which has impeded a clear view of the medium’s creative evolution. This can in great measure be explained by the paucity of early documentary evidence. Most chiaroscuros are unsigned and undated. The printmakers’ biographical details are obscure. Little preparatory material survives. Only a handful of documents have been traced, which elucidate the arrangements made by designers, blockcutters, printers, and publishers to issue these prints. And with the notable exception of the art historian Giorgio Vasari, very few contemporaries wrote about the technique and its practitioners.

In light of this, the prints themselves necessarily constituted the primary evidence for my study. While a certain amount of information can be gleaned from studying digital reproductions of a print, only through close visual scrutiny of the actual object can key material facts be discerned. For example, such physical evidence as the formulation and consistency of printing inks or the specific traits of paper were critical to identifying the characteristics of each chiaroscuro workshop’s output. Throughout my research, I collaborated with conservators and conservation scientists whose technical investigations deepened our knowledge about the printing procedures and materials employed by Renaissance chiaroscurists, connecting us more closely to their workshops and bolstering the art historical interpretations.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue present many new scientific and conservation findings and fresh art historical perspectives. They aim both to advance scholarly understanding and enhance appreciation among new audiences of these captivating works of art. It is a great privilege to bring together some 100 chiaroscuro woodcuts, alongside related drawings, engravings, and sculpture, and to share these seldom seen works with our visitors. I hope those who are able to visit LACMA will seize this exceptional opportunity to enjoy these visually arresting works in all their material splendor.

The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy is on view in the Resnick Pavilion from June 3 to September 16, 2018. Member Previews begin May 31. Not a member? Join now!