This series of blogposts will provide a behind-the-scenes look at the process involved in planning a major exhibition on ancient Colombia—Portable Universe/El Universo en tus Manos: Thought and Splendor of Indigenous Colombia—opening at LACMA in the fall of 2021. For this particular exhibition, the focus is on the compelling need for more research and our collaboration with Indigenous people in Colombia.

The Problem with an Exclusively Western Perspective

I last wrote an Unframed blog in 2016, when our research on the ancient Colombian collection at LACMA was just gathering pace and we, the curators, traveled to the Museo del Oro, Bogotá, to learn more about the objects in our collection. More questions were raised than answered during the trip, and all participating parties saw the potential for future collaboration and research. Thus, the idea of a major, co-curated exhibition on ancient Colombia was born. Three years later I am fully immersed in working on the exhibition, now titled Portable Universe/El Universo en tus Manos: Thought and Splendor of Indigenous Colombia. People often ask why it takes so long to prepare an exhibition, so this series of blog posts will provide a behind-the-scenes look at the process involved in creating this particular exhibition, focusing on the compelling need for more research and our collaboration with Indigenous people in Colombia.

Research is a key component of preparing an exhibition like this and takes a lot of time, but in this case it is especially necessary since Colombia has received comparatively little scholarly attention. For two years, we spent countless hours in libraries and museum storage facilities, studying our own Colombian ceramics collection—about which so little is known—as well as in meetings, discussions, and at a computer, scanning the world’s collections to come up with themes and object lists that we hoped would best enable us to express the significance and splendor of ancient Colombia.

The biggest challenge however, is that attempts at understanding ancient Colombian objects have been made almost exclusively from a European point of view. Early chroniclers discussed the use of gold, but they referred to it only as an index of wealth, or as idolatrous offerings to false gods. There is little in the chroniclers’ writings—and indeed in later historical writings—to identify what the native peoples themselves thought of metals and their alloys, of their specific uses and properties, or of the processes of mining and smelting. The entire symbolic context is lacking, for gold continued, and continues, to appear to Western eyes only as an economic asset. Add to this the fact that most objects we have in collections today were originally found by looters and treasure-hunters who recorded no information about the context in which the pieces were found, and you realize how little we truly understand about these objects.

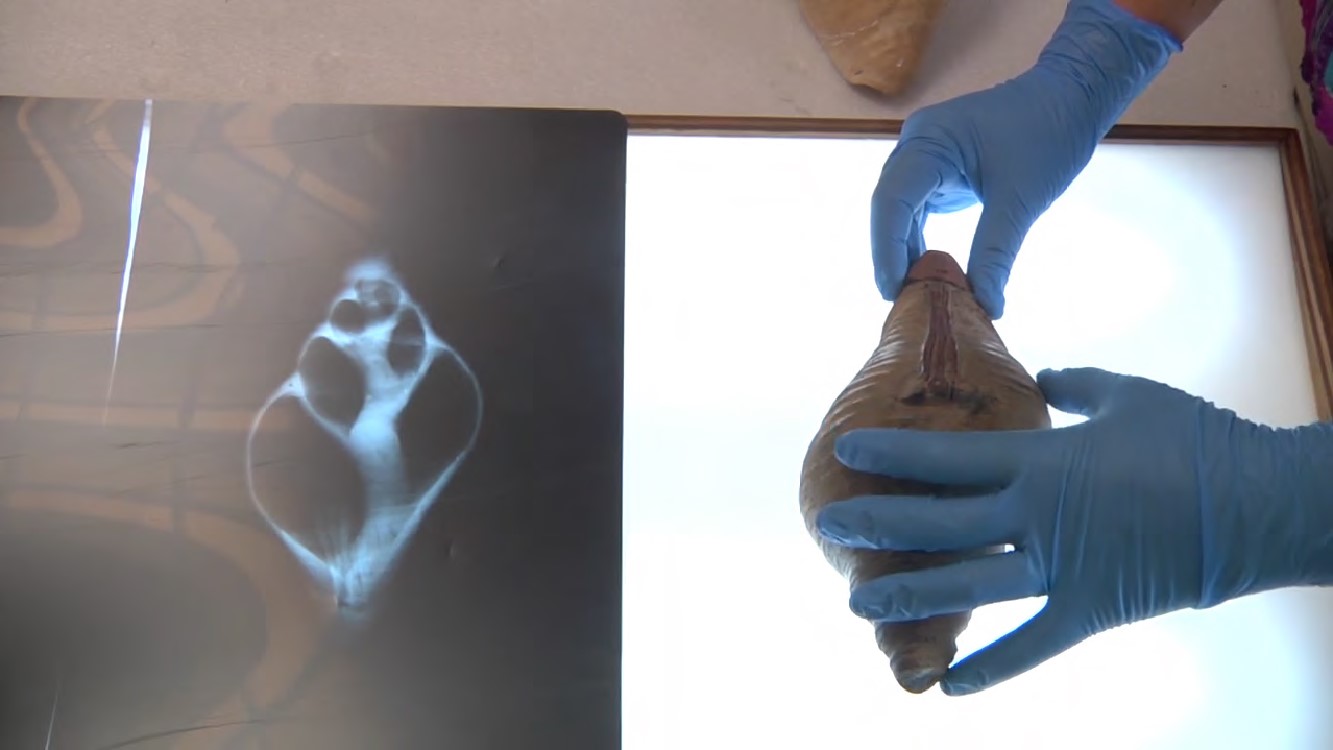

In the last 20 years, research conducted by the Museo del Oro in Colombia has advanced our knowledge of ancient gold objects tremendously. We know much more about how metalworks were made, about how lost-wax casting by one cultural group differed from that of another, and what exact proportions of copper, silver, and gold made up the alloys desired by ancient metalsmiths of different societies and time periods. However, the focus on metal objects is a legacy of that European perspective; ancient Colombians also created masterful works out of other media, such as clay. LACMA’s collection of ancient Colombian material consists almost exclusively of ceramics, so we have been furthering research in that medium: visual examination, x-rays, XRF, microscopy, and sending samples for thermoluminescence dating. A key objective of this research is always to figure out how the objects are made, which would enable us not only to understand them and their makers better, but also to identify forgeries.

However, all these technical analyses did not make us feel like we truly understood the significance of these objects. It seemed as though the essence of the cultures and histories they represented kept eluding us. Something was missing, and we wanted to get closer to the context and worldview within which these objects were created. But how do you do that, when the people who made the objects lived 500, 1,000, 1,500 years ago? How do we understand the thinking of another culture—one nearly obliterated by the Spanish conquest—built upon values that are fundamentally different from our own? The objects themselves are our most direct link to the past, and studying them in detail is the starting point. Archaeological sites and excavations can also reveal a lot, but the next closest link is the descendants of the ancient cultures we are trying to understand; the present-day Indigenous societies of the Americas.

Indigenous people in Colombia have often been excluded from formal discussions of the past, and how the Colombian past is represented has been largely determined by Western institutions. To break this, real collaboration, understanding, and openness is needed. By co-curating with Museo del Oro, LACMA was already working with Colombian peers, but both LACMA and Museo del Oro are Western institutions. We wanted to go further by not only soliciting the help of Indigenous communities in Colombia, but by creating true collaboration where the Indigenous communities were consulted as true experts of their worldview and could have input in the story of their past and its meaning.

Tune in next week to read about our first meetings with the Arhuacos—an Indigenous community we sought out to collaborate with for this exhibition.