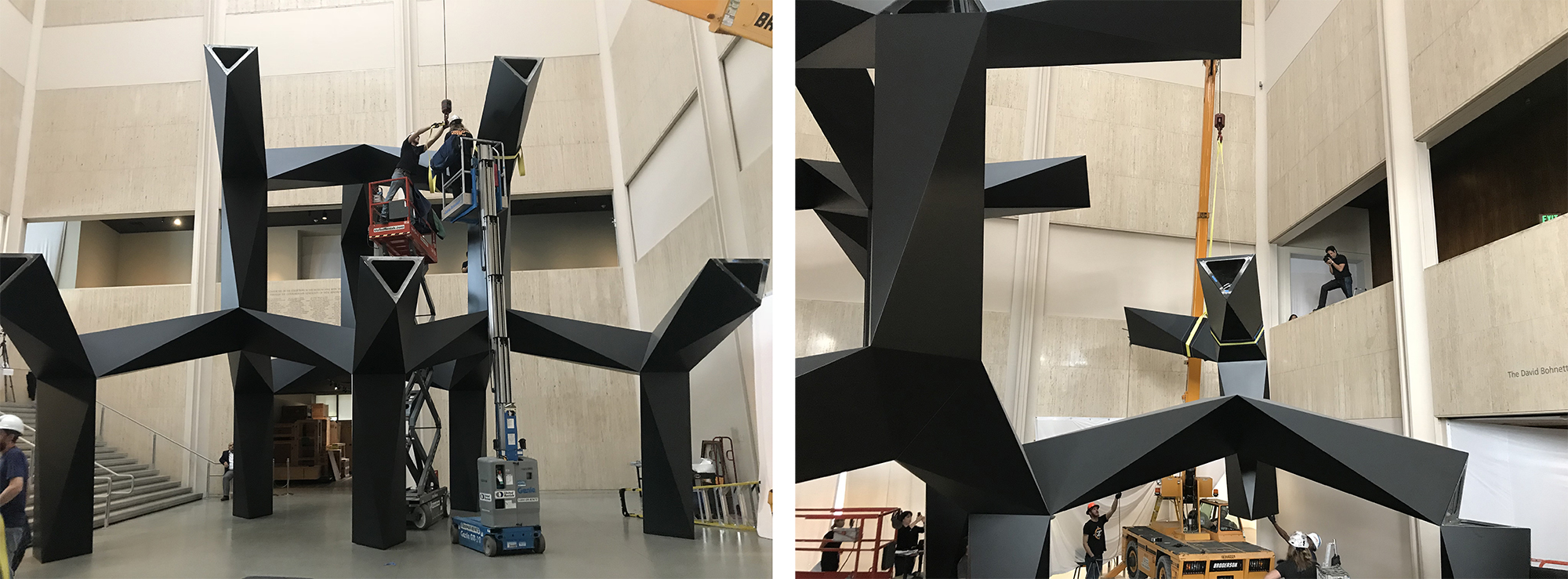

How does a 14,300-pound sculpture measuring 24 x 47 x 33 feet get out of (and how did it get into?) a building where the largest doorway is only 11 x 6.5 feet? In pieces.

Part of the brilliance of Tony Smith’s Smoke is the engineering and seamless fabrication that went into realizing the artist’s vision. The 45 units that attach together to become Smoke are identical. There are another five “knees” (two triangles connected at an angle) and 16 triangular access panels or cover plates. Each of the 45 hollow geometric units weighs about 300 pounds and is made of painted aluminum plate attached to an aluminum framework. These pieces are all bolted together. From the inside. It turns out one of the challenging—and fun—parts of assembling or disassembling this sculpture is the part when you have to be on your belly inside of it, in the dark, with a ratchet and a wrench. You have to shimmy through the tunnels on your elbows and you don’t want to drop anything down one of the legs. There are ladders inside each vertical element so you can travel to every part of the sculpture once inside, but it is hot, pitch black, and the airflow is limited.

In addition to the Herculean challenge of inventorying and packing over 130,000 objects and moving them out of the four buildings that are now closed in preparation for the construction of the new building for the permanent collection, LACMA’s Collections Management team (dubbed PACMA for this effort) has deinstalled and packed over 100 large-scale, heavy, or complex objects previously on view around the campus. Some of these they deinstalled themselves—or in collaboration with my team (Art Preparation & Installation)—while for others, like Smoke, we collaborated with a company specializing in rigging large and heavy artworks.

Senior associate registrar Linda Leckart and senior collections management technician Emory Marshall planned and managed the logistics for the larger sculpture deinstall projects, and for Smoke, we collaborated with Wolf Magritte, a company based in Missoula, Montana to do the rigging. The Wolf Magritte team, led by owner/operator Luke Boehnke (who also operated the crane) included Tyler Warren, Peter Rybchenkov, and Kyle Carlee—who did the spelunking. Special projects lead Jordan Mesavage, senior art preparator Shorty Arciniega, senior art preparator Michael Price, and I, rounded out the team from Art Preparation & Installation. We supported Luke and Emory when needed, and took notes on what order the parts were deinstalled in and how we could improve the process in the future. Senior art preparator Giorgio Carlevaro took time-lapse photography of the whole process from different angles. Documenting the project were assistant registrar Martha Rocha and registration administrator Biaani Carrillo-Muñoz from the Collections Management team, and senior photographer Yosi Pozeilov (who also documented most of the installation process in 2008) from the Conservation Center.

A year ahead of time, Linda and Emory met with head of Objects Conservation John Hirx, who provided information on the care and maintenance of the sculpture’s surfaces, and helped locate the primary access panel. They also met with Yosi to look through the images he had taken of the installation process to get an understanding of what would be required to dismantle and safely transport and store the artwork. In addition, they read correspondence and documents from files.

Once Luke was on board, we all met to divide responsibilities and discuss the process and timeline. Wolf Magritte supplied all the equipment needed for the rigging, such as the crane, personnel lifts, and slings and shackles, while Emory arranged to have the existing storage mounts and pallets, associated hardware, and the assembly jig transported to the museum, plus a forklift to stack the units, once in their storage mounts, onto pallets. Luke and Emory opened an access panel to look inside the sculpture months before they would deinstall it. Linda kept an open dialog with team members and made sure our colleagues in Facilities, Security, and Visitor Services were informed of the schedule.

The process went very smoothly thanks to the expertise of all involved.

The Deinstall Process—In Photos:

Upon arrival, the Broderson carry deck crane barely squeezed through the doors into the Ahmanson building. We literally had about an inch of space to spare. The crane position was determined by calculating the angle and length of the crane boom and figuring out the path of travel of each section of the sculpture. Once the crane was in position and ready for the first few picks, a vent was run to take the engine exhaust fumes outdoors.

The team removed the triangular access panels and two-sided “knees” while Kyle stayed inside the sculpture to unbolt the sections from each other.

-2.jpg)

From outside the sculpture, Tyler and Peter wrapped slings around the first section of Smoke, with custom-made pads to protect the painted surface from being abraded or burnished by the slings. They hooked the slings up to the crane, and Luke applied just enough tension to allow the bolts to come out. From the inside, Kyle loosened bolts at the three connection points, listening for instructions from Luke. When the first section was detached and in the air, Emory and Peter kept it from swinging or rotating.

The team lowered the first section onto the assembly cradle. Michael, Jordan, and Peter handled the leg of the section, while Tyler, Shorty, and Kyle caught the arms as they came down, and Emory, Martha, and Biaani observed. At the beginning of the video, Tyler was holding a tagline, used to control the object and keep it from spinning or swinging while in the air. Once each section was lowered onto the assembly cradle, the crew took it apart.

Over the course of the deinstall, Kyle loosened bolts and listened for instructions from Luke while inside the sculpture. Martha and Biaani worked to record the numbers of each unit and collected lots of data and information that will be helpful when it comes time to install Smoke again. We used this opportunity to verify the numbering on each part and make a digital model documenting where each unit goes and which sections came off in what order.

Yosi photographed the process, taking overall shots and details to note how sections fit together and also to document any condition issues.

Each section of Smoke consists of two, three, or four individual units that come apart and get bolted at each end to a steel frame with wheels on it to make transportation easy.

The last two sections were anchored to the floor with straps to keep them standing and stable when the third to last section was removed, until they too were each hoisted onto the cradle for disassembly.

During the deinstallation, Kyle found a note left inside Smoke by Adam Swisher in 2008—the last technician who had been inside the sculpture—with the optimistic sentiment that he hoped "the future is a place of respect for the environment, extinct racism, healthcare for everyone, peace on earth, and love of life."

Once the units were in their storage mounts, they were taken up the freight elevator to the Los Angeles Times Central Court (LATCC) where Emory, Shorty, and Michael stacked four to a pallet and wrapped them for storage.

Three tractor-trailers took the sculpture to its temporary home in storage. Though we had planned for up to eight days for the deinstall, it was done in four, including palletizing and wrapping the parts. We look forward to installing Smoke again in the future!