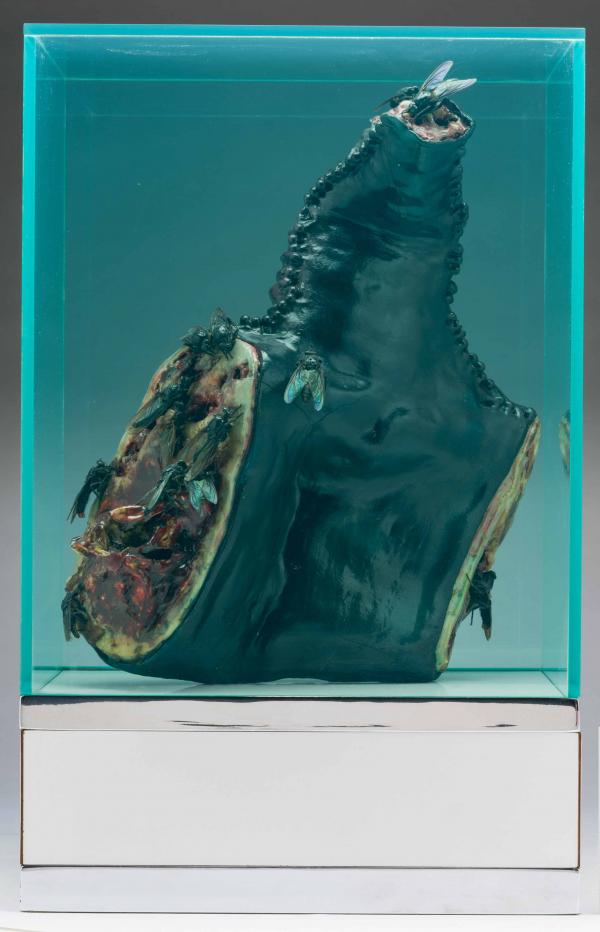

Art conservation is a fascinating and complex profession. As an objects conservator, I get to work with some pretty unusual yet equally fascinating objects. This was the case for Paul Thek's Untitled (Meat Piece with Flies) (1965) from the series Technological Reliquaries, part of LACMA’s permanent collection. The object is unusual mainly because the materials it is made of include Plexiglas, metal, and real flies.

A few years ago this object traveled internationally to be part of an exhibition, but upon returning to LACMA it was noted that the object sustained some visible damage during transit. Yes, despite all the precautions, best practices, and knowledge that goes into prepping objects for travel, on a very rare occasion damage does happen. Because objects like this one are often made from unusual materials using unconventional techniques, they can present conservation and handling difficulties that old masters artworks do not.

Initial visual assessment of the object, after it was unpacked, revealed that not only had the artwork sustained some surface damage but possibly some internal, structural damage as well which could present a unique set of challenges. Unlike when a conservator treats a classic artwork, where in many cases extensive conservation literature may exist providing a road map for treatment, objects like Paul Thek’s require an open mind and creativity in solving the issues at hand along with following some well-established steps.

Many people think art conservation is a single person doing the treatment, but in fact it is a very collaborative endeavor. After discussing with the curator, conservators, scientist, and conservation photographer, an action plan was developed. The first step in what became a six-month-long conservation treatment was to remove the Plexiglas case, or vitrine. Having some institutional knowledge on how to open and remove the Plexiglas case certainly helped because Paul Thek, like many artists, did not leave behind any handy instructions. Although the piece was slightly leaning and resting on one side of the vitrine, it was determined that it was stable enough and therefore safe for the Plexiglas vitrine to be removed. Once the case was taken off, the extent of the surface damage the object had sustained was revealed in even more detail. Some areas of the wax surface appeared slightly crushed and abraded, while other areas on the bottom of the piece had sustained some losses and several insect legs and half of a fly’s body was detached.

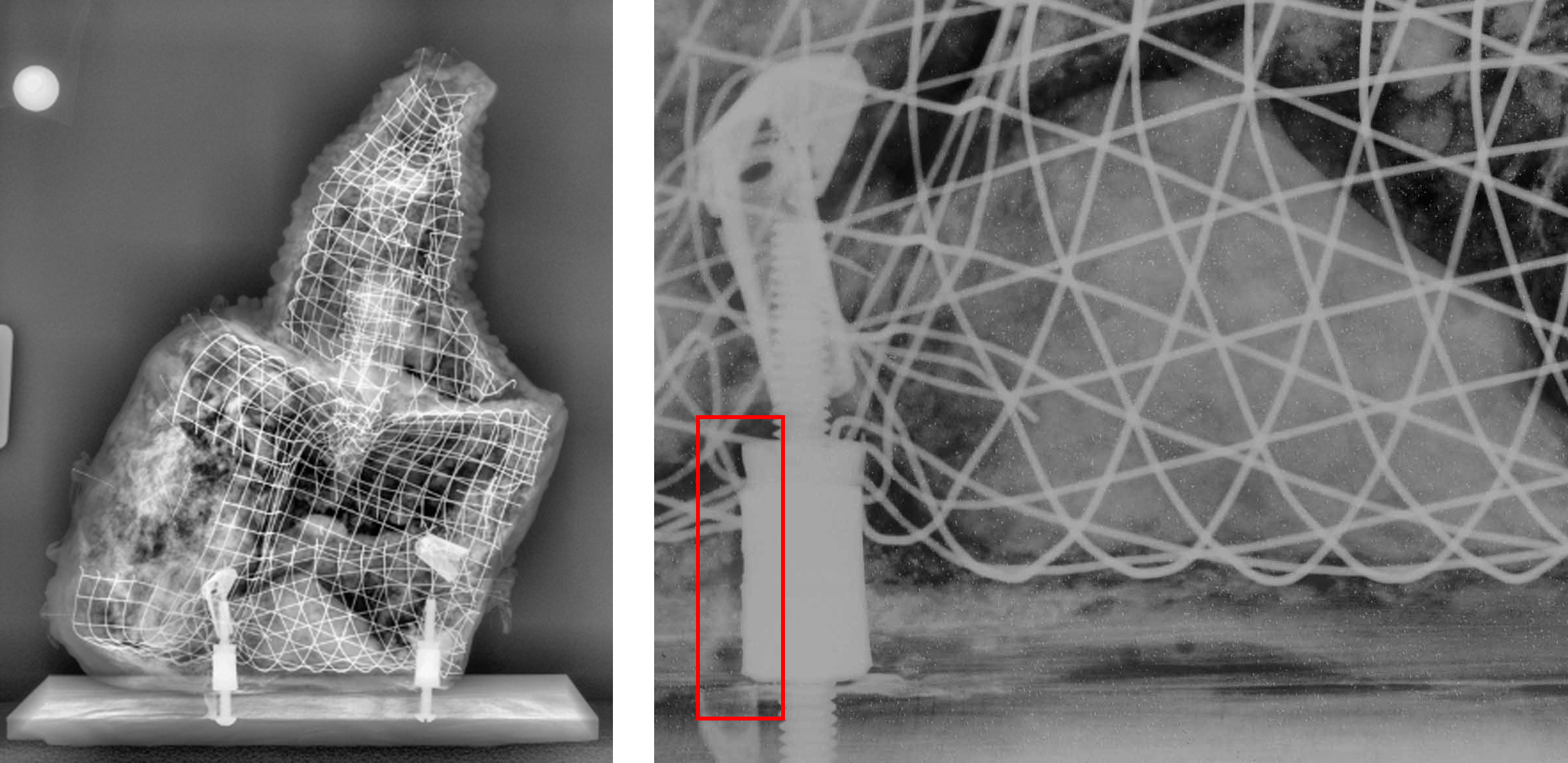

How the object was attached to its base was a big mystery, since the sculpture felt relatively loose. There was no information regarding its structure or manufacturing process. After proper photo documentation done by our Senior Conservation Photographer Yosi Pozeilov the next step was to X-ray the object. Using a portable X-ray unit, Assistant Conservation Scientist Laura Maccarelli and Yosi were able to take several radiographs of the object revealing some of its structural secrets.

The X-rays revealed that the object had an internal metallic mesh structure, two lead anchors, and two seemingly randomly placed metal “butterflies.” On closer examination of the X-ray it was noticed that one of the lead anchors was slightly detached from its plaster surrounding, visible in the image above, revealing the reason why the object felt loose.

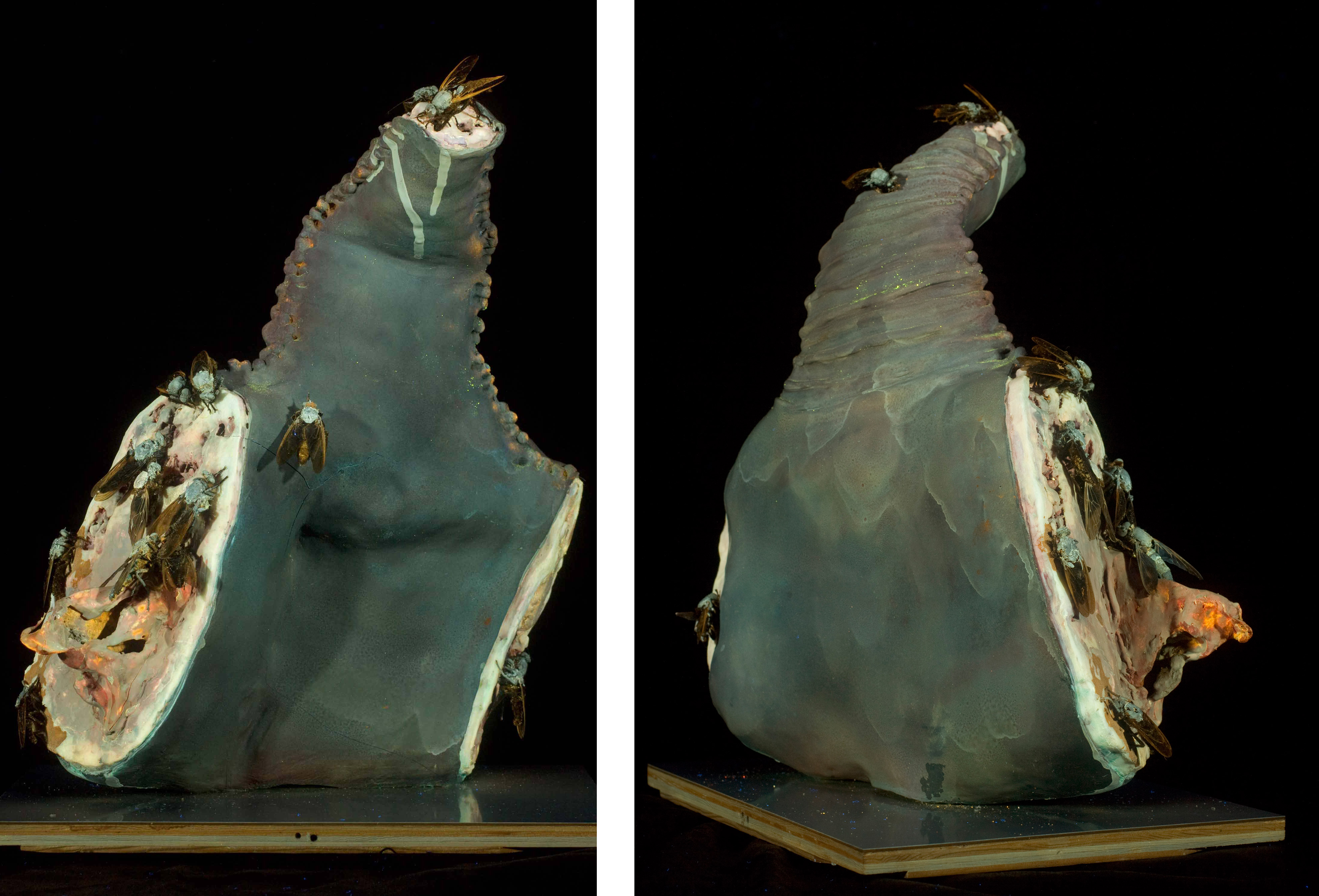

As part of the preliminary investigation, a series of florescent UV photographs were also taken with the hope that they might possibly reveal previous interventions. None were observed, but it revealed how some of the flies were attached and an application of surface coating.

Once the investigation phase was concluded, the next step was to begin the actual conservation treatment. The object was carefully positioned horizontally on its back to avoid crushing any of the fragile flies. Having the object lying flat allowed me to access the loose lead anchor. After removing it, a series of steps to consolidate the core plaster was conducted by injecting acrylic adhesive along the break and surrounding area. Once the consolidation step was completed, the lead anchor was repositioned and secured using the same acrylic adhesive, but at a higher concentration to ensure a good adhesion.

With the consolidation and repositioning of the anchor completed, focus shifted to the wax surface. The loose fragments were reattached using a combination of heated spatula, and at times solvents, allowing for a better bond between the fragments and the rest of the object. Unfortunately, some small areas of wax were completely lost and new fills had to be made from a pigmented mix of microcrystalline wax and beeswax which resulted in an almost perfect match with the surrounding areas. The few small crushed wax areas were reconditioned with a diluted solution of mixed waxes which allowed for re-saturation of the areas and slight reshaping.

Some of the most fun, but extremely challenging, parts of the treatment were reattaching the fly’s body and identifying the locations of and re-adhering all the loose insect legs. After unsuccessful attempts to source a similar fly, and after determining that it would have been nearly impossible to remove the original fly without causing some damages to the surrounding area of the sculpture, it was time for some creative solutions. Various ideas were explored, from leaving the fly as is (without a body) to using insect pins to trying an adhesive for reattachment.

When I looked closely at the fly and its body under magnification glasses, I noticed the body had a relatively small, flat surface at the break and the loose body part was hollow. At that moment the solution became evident. I would insert a small support in the loose part of the body and then reattach it to the rest of the fly. Two small caped tubes were made using Japanese tissue and Jade PVA adhesive. The two tubes were slightly different sizes and only one was inserted and secured in place with Jade PVA followed by the reattachment of the body part to the rest of the fly. The same adhesive was used to reattach all the loose insect legs, thus reinstating the object to its original look. As a final step, the object was reattached to its base and the vitrine was repositioned, bringing the sculpture to life once again.

While some people might find this object unappealing to look at given its uncanny realistic look of a rotting piece of meat with flies, as an objects conservator I find this sculpture to be quite fascinating not only from a technical perspective, but also because of its ability to engage viewers and cause strong reactions. Sometimes the most unusual conservation projects can be the most rewarding ones.