In an earlier Unframed post, we introduced the Domus armchair, one of the pieces that will be featured in the upcoming exhibition Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890–1980 (summer of 2022). This chair designed by Finnish interior architects and designers, Annikki Tapiovaara (1910–1972) and Ilmari Tapiovaara (1914–1999) required treatment in both the object and textile conservation labs.

Treatment of the Problematic Chair Frame

A common manufacturing process of post-World War II chairs is the finishing of wooden frames with a sprayed application of nitrocellulose lacquer. Invented in 1921 by DuPont employee Edmund Flaherty, nitrocellulose lacquer is formed by dissolving cellulose nitrate in a solvent mixture and plasticizing materials that enhance the durability and flexibility of the resulting lacquer solution.

Unlike previous lacquer products, nitrocellulose lacquer can be colored with a variety of pigments and dyes and is able to be sanded to a mirror-like finish. The easy customization of this new lacquer along with a faster drying speed encouraged the rapid adoption of nitrocellulose within the car industry and furniture and musical instrument manufacturers. Unbeknownst to them, the aging properties of nitrocellulose lacquer are far less desirable. Many of the furniture pieces treated with this lacquer now show cracking and flaking of the lacquer. In furniture, these are most apparent in common areas of stress, such as chair arms and legs. Light wood exposed by the loss of lacquer darkens quickly as a result of dirt particulates becoming ingrained in the pores of the wood.

For the conservation of the Domus armchair, object conservator Don Menveg devised a treatment that would stabilize the nitrocellulose lacquer and even out discoloration of the wood. The entire frame was cleaned using an aqueous emulsion solution designed to address different types of soiling, such as ingrained dirt and residual wax. Once it had been cleaned, a French polishing technique was used to relacquer the entire frame. This step of the treatment saturates areas of exposed wood, giving the frame a uniform finish and seals the edges of the old nitrocellulose lacquer.

The Whole Three Yards: Reproduction of the Upholstery

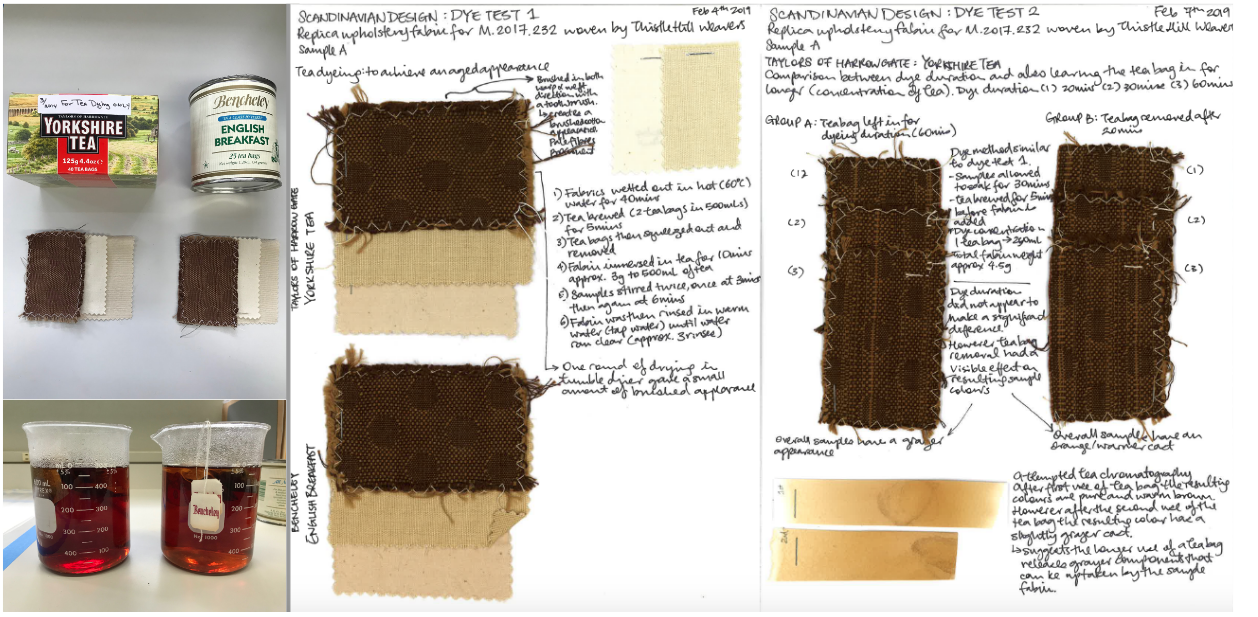

The reproduced upholstery was to be made as close as possible to the original, preserving the original upholsterer's intention. The reproduction fabric woven by Rabbit Goody at Thistle Hill Weavers was very close in color to the original fabric, however, the colors on the threads were much brighter and cleaner looking. To give the fabric an aged appearance the color needed to be slightly yellow, slightly gray, and darker overall. This effect can be achieved through “dyeing” with tea.

A couple of different black teas were tested, and Yorkshire tea was deemed the most successful at giving the reproduction fabric an aged tint. To “dye” three yards of fabric, the largest dye pot in the lab was used along with 15 liters of hot water and 120 tea bags. The fabric was left to simmer for 10 minutes and then thoroughly rinsed and put through the washer and dryer. This was done to remove tea that had not properly stained the fabric.

Next, patterns were taken from the original cushion, several mock-ups were stitched and tested before cutting into the tea-stained reproduction fabric. Conservation grade polyester wadding (a soft mass or sheet of short loose fibers used for stuffing or padding) and cotton quilt batting was used to pad out the cushion to a good height. The new cushion was tufted to replicate the pattern on the original cushion. A new seat cover was also made out of the reproduction fabric. It is easily removable so the original upholstery can be accessed for research purposes.

The Domus armchair will be on view in Scandinavian Design and the United States, 1890–1980, opening at the LACMA in the summer of 2022.