ArtCenter College of Design is presenting a virtual exhibition of work from the 2020 class of Graduate Art MFA students, titled Fell For Everything. Curated by artist Adam Stamp (MFA 2017), the show opened on September 12 and runs through October 3, 2020. In conjunction with the exhibition, LACMA curator Rita Gonzalez and artist and ArtCenter faculty member Diana Thater asked each of the 12 graduates to select an object from LACMA's collection and reflect on its relationship to their own developing practice. Over the course of the next month, LACMA will be posting the MFAs' texts, along with images of their personal work and the work they chose from LACMA's collection. Their thoughts on these selections provide an overview of their interests and the kinds of art historical conversations they want to have.

Juliana Halpert

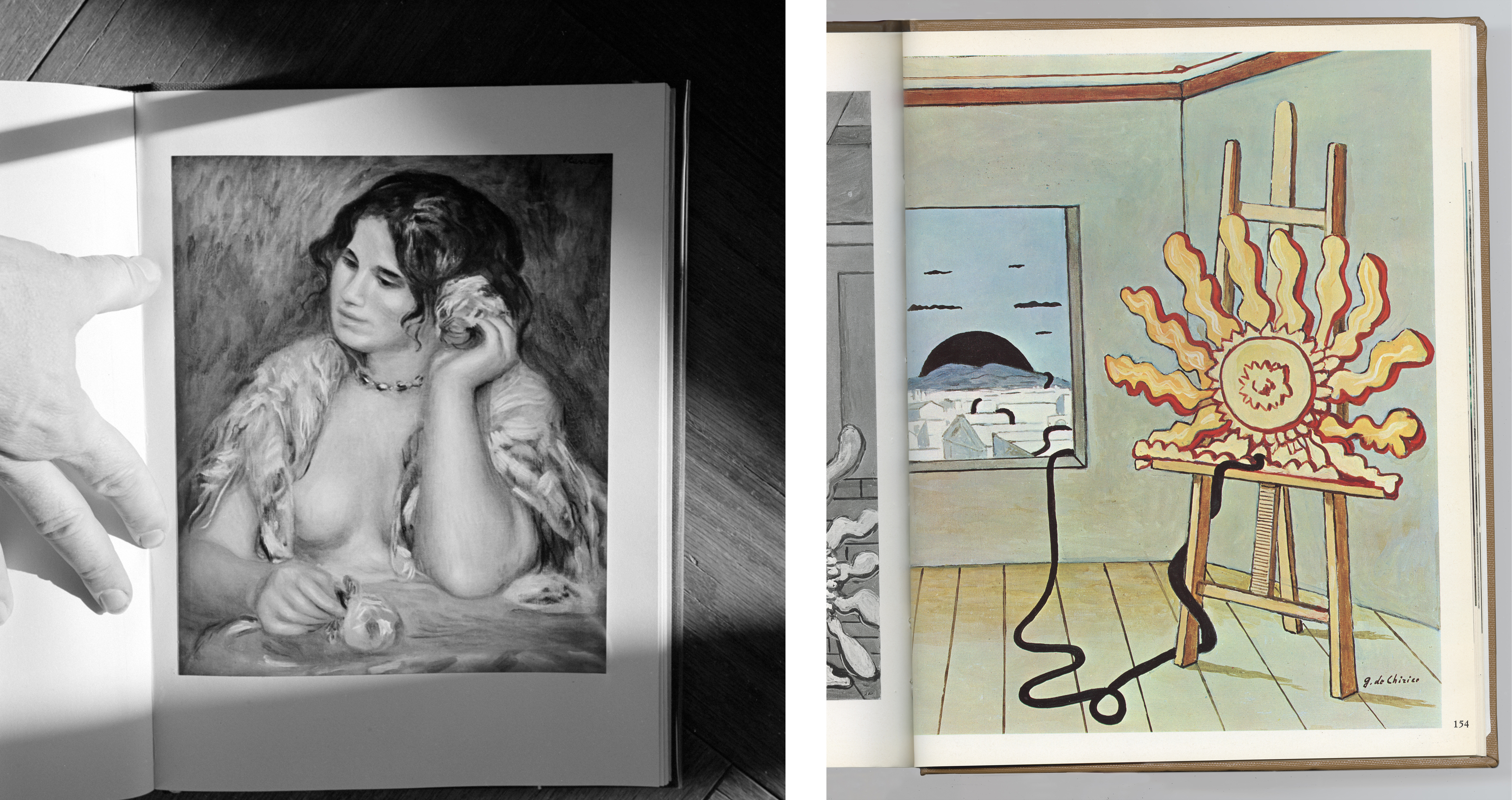

This past winter, I started making digital scans of books—large, dusty old art books, from ArtCenter's library. The school has a generous collection of aging monographs, rebound in drab orange and red and brown hardcovers, with their call numbers embossed in white or gold on the spines. Many of the pre-Modern set feature only black and white images; others include a few large color plates, glued onto the page. I've been told that the Illustration majors are supposed to use these books to complete a mandatory master-copy assignment, for which they're asked to reproduce a Rembrandt or a van Rijn or a Titian by hand. I think many of the students opt to use digital images instead, summoned by Google, of course. I've seen these undergrads stationed at the library's large tables, laboring over their large sketchbooks, jpegs of paintings levitating at the center of their MacBook screens.

I'm not entirely sure what first compelled me to start scanning spreads from these volumes, to press their thick spines down onto the Epson machine's glass flatbed and watch the ribbon of light comb every square inch of its surface. I like the way old paintings look on a printed page: flattened, yet full of aging, inky color, and given a crisp edge. How they move with the curl of a page and disappear into the dark depths of a gutter. How a page number or a caption lingers quietly nearby.

I was excited to discover Sanford Roth's Pierre-Auguste Renoir Pictures in LACMA's collection. Decades and decades ago, the photographer seemed to relish these same things. In the picture I chose, Roth's hand presses down on an opened book, holding the pages flat as it rests on a wood floor, exposing a reproduction of Renoir's 1911 painting Gabrielle with a Rose to incoming sunlight. Strips of windowpane shadows stretch across the edges of the book; the cracks of floorboards run perpendicular. The book sits low in the photograph's frame. It's a quick, quiet glance at not only a painting, but how and where this painting now lives: as a picture, on paper, printed and bound and kept on a shelf, every now and then opened up to be looked at in the light of day.

Manyu Gao

Claes Oldenburg is known for using Pop art to change life. He has always played with scale—transforming small objects into colossal ones. In this way, the city became a playroom that he could fill with toys: a teddy bear in Central Park, and a melting ice cream bar on Park Avenue. These sculptures distort the scale of the surrounding environment and remind us that one of Pop art's greatest, but often overlooked, legacies is humor. These utopian projects are witty, joyous, fun, springing up in cities all over the world. In an interview, he said, "The only thing that saves the human experience is humor."

The most popular pool game in the world is eight-ball. It is played on a billiard table with six pockets, cue sticks, and 16 pool balls: a cue ball and 15 object balls. What if the pool balls are taken out of the game and made much larger? What if the numbers on the balls are gone and become solid-colored spheres? What if they are sitting on the ground of an exhibition room? It may become more boisterous, recalcitrant, and playful, but the juxtaposition of the oversize pool balls and the stairs seems grotesque, like the giant soap placed on the regular-sized rug in Magritte's painting, Personal Values (1952). This is Oldenburg's Giant Pool Balls (1967).

With Oldenburg's Giant Pool Balls in mind, I created an installation, titled Bowl and Pool (2019). It references popular American sports: bowling, pool, swimming, and the Super Bowl, and recreates them in smaller playgrounds. One of the sculptures is a pool table containing 16 ceramic pool balls on a table constructed out of interlocking puzzle pieces. The table is taller and smaller than the original, almost like a bar table. The adjacent sides of the puzzle pieces are painted complementary colors, leading viewers to walk around to see the work, and emphasizing the importance of perspective in this game. The tabletop is not flat. Its topography references the outdoor origin of the pool game. Handmade irregular ceramic balls are arranged on the tabletop and contrast with the machine-cut puzzle pieces. Since there are no pockets attached to the tabletop, the ceramic balls will fall off and land on the rug on the ground. There is no cue ball on this table, it has fallen and sits on the rug below. This sculpture describes an absurd moment of the game—the rack of object balls has been broken, but only the cue ball has fallen off the table. Now whose turn is it?