In my first year as an Andrew W. Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow, I had the exciting opportunity to work in LACMA’s Japanese Art Department with Hollis Goodall, curator of Japanese Art, as my mentor. Having spent a large part of the year researching artists from the 20th-century Japanese print movement sōsaku-hanga (creative print), I was encouraged by Hollis to curate a selection of sōsaku-hanga from LACMA’s permanent collection for Unframed.

Through this selection of prints, I explore how these artists sought to remain distinctly Japanese while simultaneously celebrating individual expression and experimentation, and embracing Western influence.

What is sōsaku-hanga and why is it important?

Historically, printmaking in Japan was viewed primarily as a means of commercial reproduction. Beginning in the 20th century, print movements sōsaku-hanga and shin-hanga (new print) arose to challenge this notion and work toward elevating printmaking to a respected art form. While shin-hanga hoped to do so through revitalizing the traditional ukiyo-e style and collaborative printmaking process—which included a separate designer, engraver, printer, and publisher—sōsaku-hanga took on the maxim “jiga-jikoku-jizuri” (self-drawn, self-carved, self-printed) and established that a single artist complete the entirety of the printmaking process themselves.

The sōsaku-hanga movement was heavily influenced by the individualistic ideologies and modernist aesthetics of the West, yet it was important that it not be merely a copy. One of the ways sōsaku-hanga artists established a sense of national identity in their work was through highlighting traditional Japanese artistic and cultural legacies. This was intensified by the growing Japanese anthropological interests of the time and the development of mingei, the Japanese folk art movement.

This selection of sōsaku-hanga has been categorized into six different Japanese artistic and cultural traditions: Bunraku, Haniwa, Festivals, Ceramics, Architecture, and Calligraphy.

Bunraku

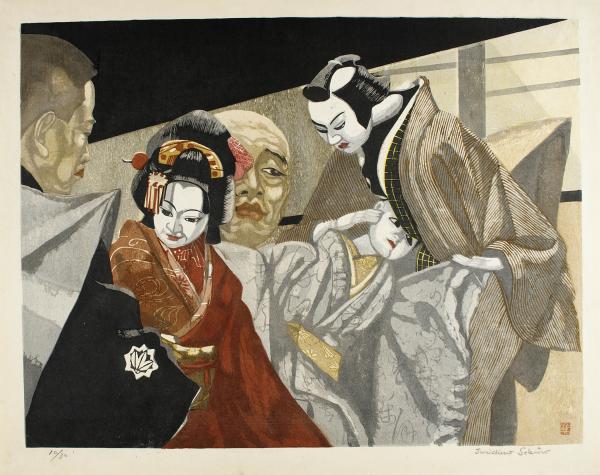

Bunraku is a form of traditional Japanese puppet theater first developed in Osaka during the Japanese Edo period (1603–1867) that combines narrative storytelling, instrumental accompaniment, and complex puppetry. The artform utilizes half-life-sized puppets that are skillfully crafted by specialized artisans and are each manipulated by three puppeteers who undergo years of extensive training.

While the puppet maker and puppeteers are usually meant to be forgotten, lost to the illusion of performance, in Sekino Jun’ichirō’s The Puppet Maker (1956) and Monjūrō Performing with Puppets (Bunraku) (1954) these puppet artists are highlighted and depicted engaged in their work. Their serious expressions show intense focus. Using expressive colors, dynamic movement, and dramatic lights and shadows, Sekino also captures the impressive scale and detail of the Bunraku puppets.

In Inagaki Tomoo’s Puppet (1945), Inagaki imitates a traditional portrait style. If not for the stiff posture and expressionless face, the puppet could easily be mistaken for human. In this, Inagaki both elevates and subverts aspects of the traditional.

Haniwa

Twentieth-century Japan was a time of heightened anthropological and archeological interests as the Japanese people sought to further understand their history and culture. Saitō Kiyoshi’s Haniwa (1950) directly reflects these interests in its depiction of a subject matter deeply rooted in Japanese history. Haniwa are ancient Japanese terracotta clay sculptures found in burial mounds and tombs starting in the Kofun period (c. 300–538).

Balancing the traditional and the modern, Saitō depicts the heads of haniwa with modern cubist-inspired aesthetics, using geometric shapes and flat areas of color. The work also impresses in its scale as each of the haniwa heads in the print are around three times larger than what would be the actual size of haniwa sculptures.

Festival Celebrations

There are a countless number of national and local festivals celebrated in Japan, with almost each major shrine having their own. These celebrations act as a sort of ritualistic reminder of culture and tradition as communities come together to partake in local customs and traditional performances, such as those depicted in the prints in this section: koto playing performed privately within the shrine to call forth the god(s) to the festival, carriage processions with a sacred palanquin that carries the god(s) throughout the neighborhood to spread beneficence, and kagura dances to entertain the god(s) and purify the land.

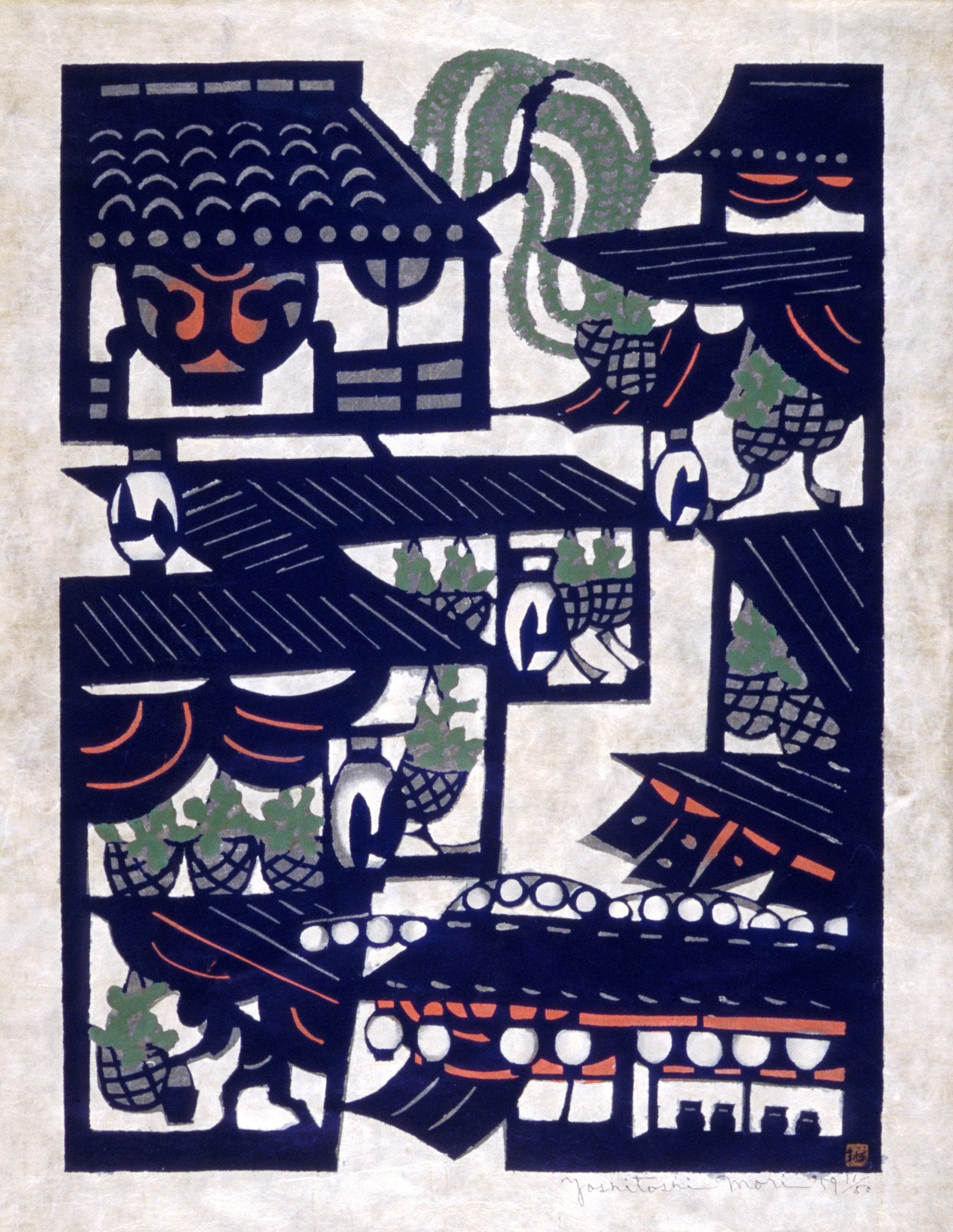

Mori Yoshitoshi often worked with stencils (katakami) which were traditionally used in dyeing fabrics and later brought to printmaking by Mori and other sōsaku-hanga artists. As a member of the mingei movement, Mori frequently took to depicting local folk traditions such as these festival celebrations. His works are dynamic in composition, involving dramatic movements and rich colors.

Ceramics

Japan is home to one of the oldest ceramic traditions in the world, one that is still vibrant today. While there was a decline in traditional crafts during the 20th century, the development of mingei helped to revitalize ceramic-making with an emphasis on those crafted by hand, but in high quantity, inexpensive, and designed for everyday use. Such a kiln site is depicted in Masumi Tadao’s Crockery Maker (1933), contrasted by Urata Giichi’s Jar (1932), which features an artistic ceramic ware made for display and flower arrangement, rather than daily use.

During the 20th century, wood-burning kilns were still allowed in urban areas, often clustered throughout the city where ceramics would be both made and sold, as depicted in another of Mori Yoshitoshi’s stencil prints, Shop Lane (1959). Both Shop Lane and Masumi’s Crockery Maker reflect a reportage style of depiction that the sōsaku-hanga movement favored over the beautified and idealized depictions of the shin-hanga movement.

Architecture

The mid-20th century was a time of severe political upheaval, violent conflict, and rapid urbanization. In this, many sōsaku-hanga artists saw the need to capture important national and cultural sites as an act of preservation. Yamaguchi Gen’s Meiji Shrine (1945), from the print series Scenes of Last Tokyo, memorializes the Shinto shrine dedicated to Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken that had been destroyed by air raids during World War II. While the Meiji Shrine was rebuilt in 1958, the print holds the memory of the original building and reminds viewers of its significance.

Prints by Yoshida Tōshi and Kawanishi Hide depicting the same subject matter—stone gardens—exemplify the individualist nature of sōsaku-hanga in displaying each artists’ different stylistic approaches. Embracing the experimental and avant-garde spirit of sōsaku-hanga, Kawanishi strips down the image of the stone garden to its most basic shapes and forms, absent any highlights, shadows, or outlines as compared to Yoshida’s work. Kawanishi also uses a unique embossing technique to create the rake lines in the sand, so subtle that it could not be captured in the photograph of the artwork.

Calligraphy

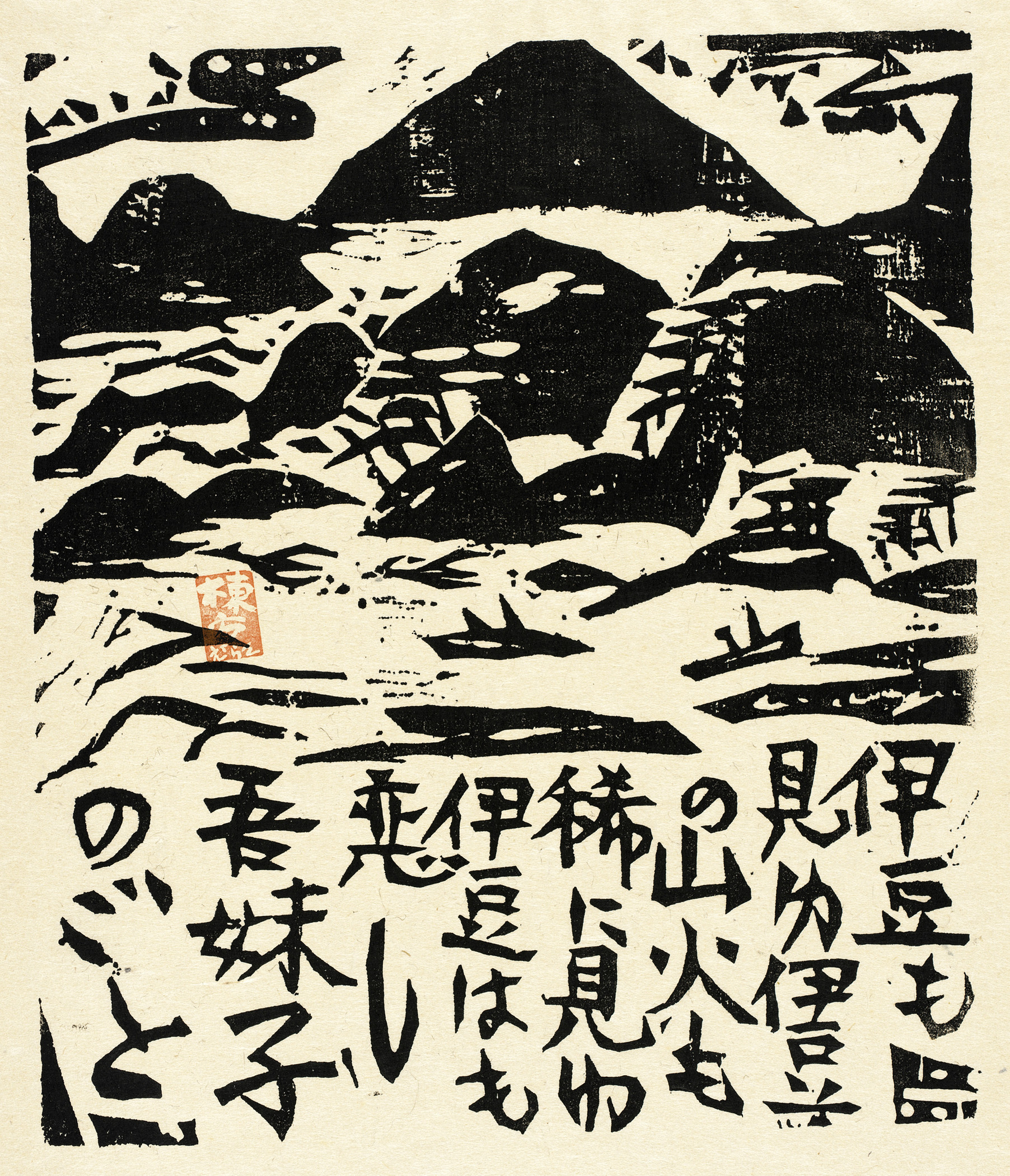

Calligraphy stands as one of the most highly regarded forms of art in East Asia. In the prints featured in this section, artists Munakata Shikō and Maki Haku synthesize aspects of calligraphy in their work through their individual expressive and abstract styles.

Munakata’s Yamabi (1958) is part of his series of 31 prints based on a poem by Yoshii Isamu, a poet and playwright who was Munakata’s contemporary. This specific work depicts the mountain range of Izu that halfway down the print transitions into stylized calligraphic text.

Maki Haku’s works abstract individual kanji characters to a point of unrecognizability, homing in on their artistic forms. His works are deeply embossed to make prominent the sculptural and three-dimensional quality of prints. Maki also highlighted the unique textures of the concrete or the grain of the wood on which he made his prints.

As artists of the sōsaku-hanga movement broke away from traditional Japanese printmaking practices to instead embrace a spirit of individuality and experimentation, drawing aesthetic influence from the West, the prints included in this selection show how some artists sought to balance the tensions between individualism and nationalism, traditional and modern, Japan and the West through the exploration of distinctly Japanese subject matter.