Look out for Chris Burden’s Full Financial Disclosure on Tuesday, September 20, on Snapchat to commemorate the 45th anniversary of the work’s display on television. Learn how to use Snapchat. Learn more about the way artists have usurped forms and sites of advertising to disrupt viewers’ expectations in Objects of Desire: Photography and Language of Advertising, on view through December 18.

Chris Burden was 27 and fresh out of graduate school when he began purchasing commercial advertising time from local stations in Los Angeles and New York. He sought, in his words, to “break the omnipotent stranglehold of the airways that broadcast television held” by airing a series of advertisements of his own creation. While in graduate school at the University of California, Irvine, he had performed actions that often put him at risk of exhaustion, injury, or death; in his infamous Shoot (1971), he sustained gunfire to his arm. In a related gesture, Burden countered the aggressive presence of television advertisements by authoring his own. “It felt that the TV, that that form of media, was basically a one-way street. That it was just screened at you.”

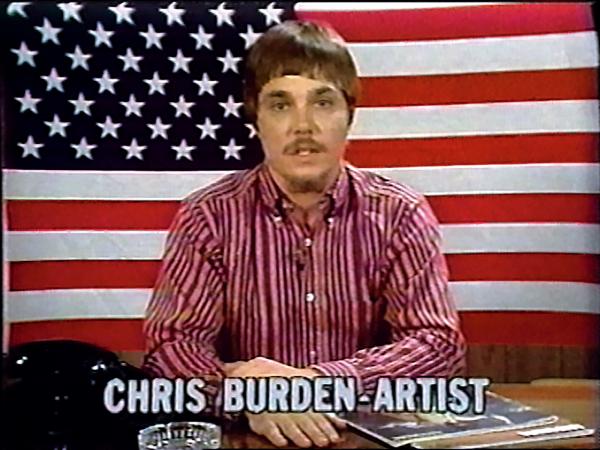

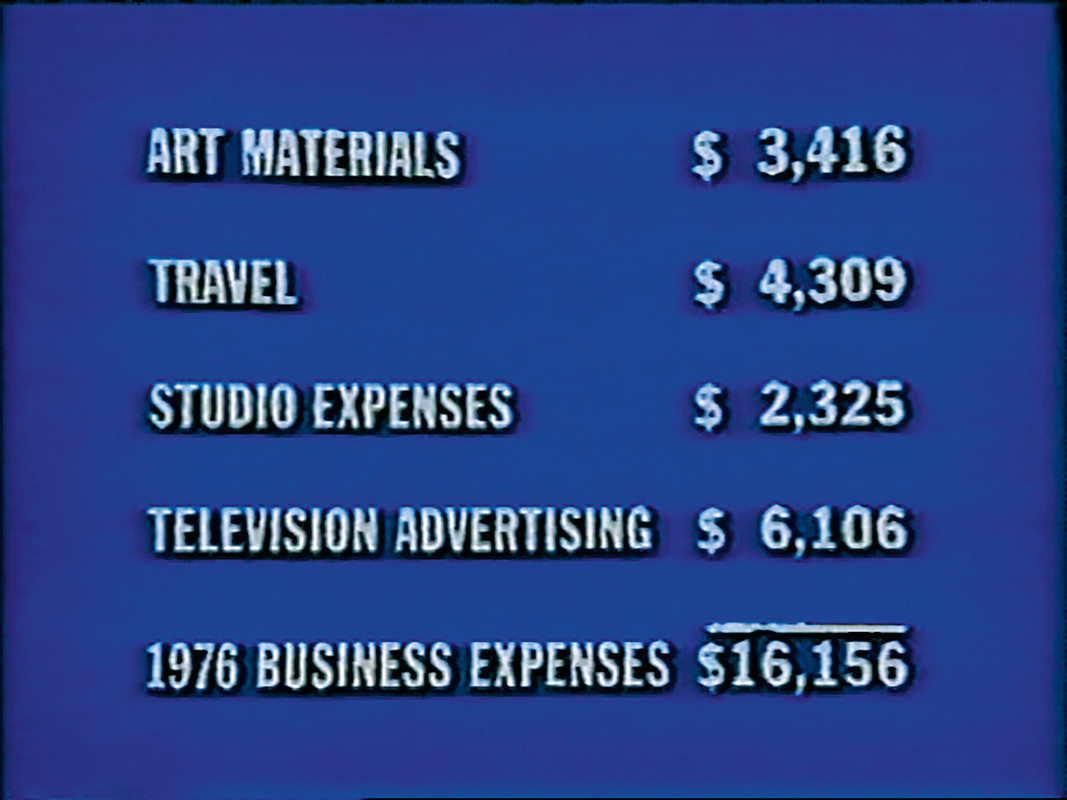

Burden made Full Financial Disclosure in connection with his exhibition at Baum Silverman Gallery, Los Angeles. The work aired 30 times on Los Angeles airwaves in the fall of 1977. Sitting in front of an American flag at a wooden desk equipped with a rotary telephone, ashtray, and magazines, Burden confidently confronts the camera in the manner of a politician or news anchor. He explains to his audience, “In keeping with the bicentennial spirit, the post-Watergate mood, and the new atmosphere on Capitol Hill, I would like to be the first artist to make a full, public financial disclosure.” Burden narrates his annual revenue and expenditures as they appear on screen, including his art material, travel, studio, and advertising costs. Back at the gallery, Burden exhibited his canceled checks, bank statements, and income tax return for 1976.

In the early 1970s, television brought the unfathomable footage of the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing along with shows like Bonanza, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Mod Squad, and The Dean Martin Show into American living rooms. Commercial advertisements were constant, interrupting news and popular television shows with brand messages, mascots, and jingles. Burden identified a major loophole in the grand media-advertising scheme: what could a commercial advertisement be and do in the hands of an artist?

Burden commanded the attention of millions when they could not just simply fast forward the ad or reach for the remote: “you realize they’re all getting your message whether they like it or not.” Burden’s satire disturbed the monotony of saccharine sales pitches and escapist fictions. His commercials anticipated methods that unfolded in the 1970s and '80s, as artists turned to video as an increasingly relevant and powerful mode of expression alongside its cousin, photography.