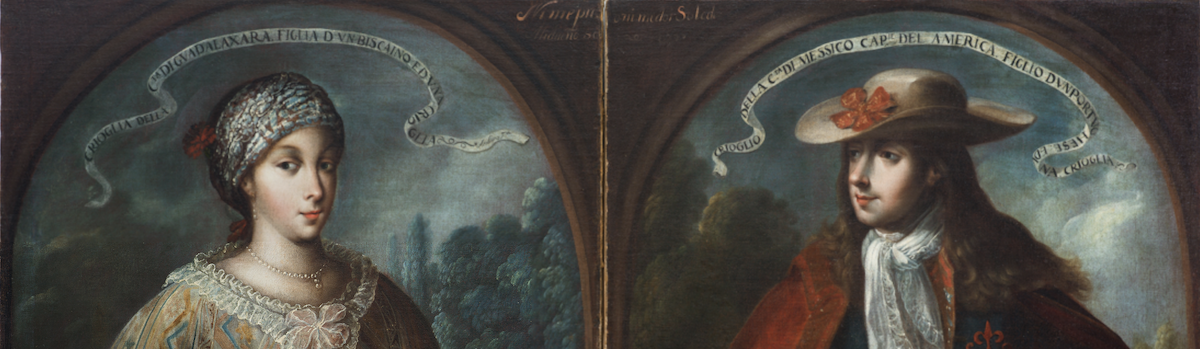

This week we added a unique pair of paintings by Manuel de Arellano (1662–1722) to the collection. The works are remarkable in terms of their execution, subject, and pivotal place in the history of 18th-century Mexican painting. Conceived as a pair, they depict a man and a woman within a fictive oval frame, a format traditionally reserved for distinguished figures. Yet, they are not portraits of actual individuals but of different racial types. In fact, these two paintings are groundbreaking precursors of the famous casta (caste) paintings, a distinctive pictorial genre invented in Mexico to depict multiracial families that spanned the entire 18th century.

Manuel de Arellano came from a prominent dynasty of artists active in Mexico City. He trained with his father, Antonio de Arellano (1638–1714), and by 1690 he was working independently and creating paintings marked by a great deal of experimentation. These works developed during a period of political shifts and mounting social and racial tensions in Mexico City. In 1692, just a few years before the ascent of the Bourbons to the Spanish throne (1700), a major riot erupted in the main square, when the Indigenous population and mixed-raced working-class, outraged over the scarcity of basic food staples and the mishandling of power, set fire to the viceregal palace, threatening to overthrow the colonial government.

Spaniards born in the Americas—known as Criollos (Creoles)—grew equally frustrated with imperial authorities, who treated them as second-class citizens and often passed them over for important civil and ecclesiastical posts. Added to this, the common misconception in Europe that everyone in the Americas was a degraded hybrid further tarnished the reputation of Creoles, casting into question their ability to rule. Arellano’s works responded to these concerns by constructing a view of a mixed yet orderly and prosperous society. His monumental view of the transfer of the original image of the Virgin of Guadalupe to her new shrine is a tour de force that captures Mexico City’s complex social hierarchy in minute detail.

LACMA’s new acquisitions are the first paintings to single out Mexico’s diverse population, setting forth the path for the development of casta painting across the 18th century. The inscriptions on the works identify the racial types and situate them geographically. They read: “Creole Woman from the City of Guadalajara, Daughter of a Basque Man and a Creole Woman” and “Creole Man from Mexico City, Capital of America, the Son of a Portuguese Man and a Creole Woman.” The unusual scrolling banderoles in Italian may be related to the original commission and their intended use, a subject that requires further study.

In the 18th century Mexico City was one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities in the world, brimming with luxury goods gathered from around the globe. Arellano emphasizes the city’s grandeur by describing it as the “Capital of America,” and portraying the figures dressed in colorful and lavish attire. The man wears an idiosyncratic Anglo-French three-piece suit—a hallmark of modernity—combined with a Spanish cape, broad-brimmed hat, and white neckcloth or cravat. The red insignia embroidered on his velvet jacket signals his knighthood as a member of the prestigious religious and military Order of Santiago. His sword—a privilege allowed only to Spaniards—reinforces his high social standing.

The woman wears a combination of local and European clothing, including a diaphanous Indigenous blouse (huipil) with intricate geometric and animal motifs, trimmed with expensive Flemish lace. This loose blouse continued to be worn after the conquest by Indigenous women, but also by Creole ladies as a sign of their pride in the land. Her head covering, made of a richly patterned silk painted masterfully with impressionistic brushstrokes, recalls those worn by women of African descent in Mexico, and is adorned with a carnation that symbolizes marriage. She is also festooned with an abundance of pearls, associated with the legendary riches of the Americas since the conquest.

The paintings might be part of a larger set of pictures of individual men and women representing various castes, displayed in Madrid’s Exposición Histórico-Europea (Palacio de la Biblioteca y Museo Nacionales, 1892–93), of which only two other pairs have been identified to date (Denver Art Museum and the Museo de América, Madrid). The works are inspired by European costume books and the tradition of representing people from around the world, which Arellano brilliantly reformulated to codify Mexico’s population and ingenious sartorial practices, giving back the first images of their type created by a local artist. This was revolutionary.

The paintings stand out for their radical informality and seeming naturalism. Boldly placed near the picture plane, both figures are slightly angled and gaze sideways, as if caught off-guard in an intimate moment. The man reaches into his pocket, as he holds a cigarette he’s about light-up in the brazier carried by the boy behind him. The woman pulls up her blouse with one hand to reveal the blue skirt underneath, and lays the other on her sumptuously bedecked canine companion, a traditional symbol of loyalty and wealth.

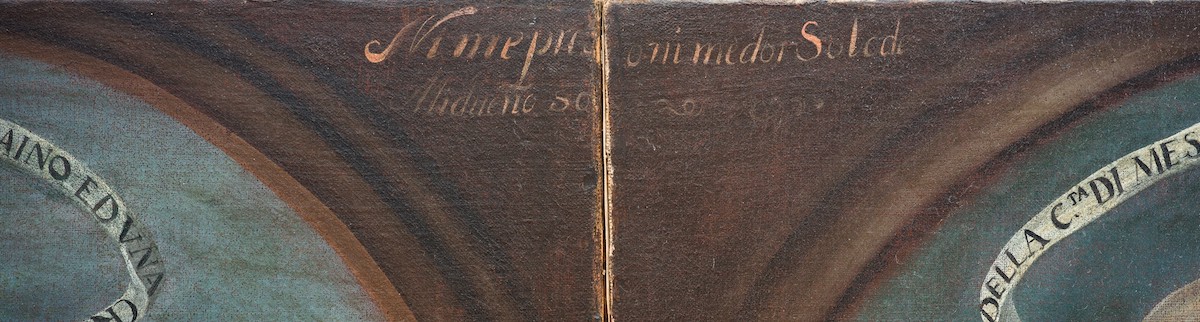

The paintings, which might have been part of a single canvas that was cut, were meant to be hung together to decipher the cryptic inscription on top: “I neither lend nor give myself, I belong only to my master” (“Ni me presto ni me doy, solo de mi dueño soy”). This popular Spanish phrase reinforces the idea of marriage implicit in this gendered pair—in this case between two figures of equal socioracial standing. It could also refer to the original owner of the paintings, who remains unknown. Intended for export to Europe, these pioneering works provide a glimpse of colonial life generated by a local artist and are fascinating for what they reveal about Mexican painting, the development of casta painting, and the significance of dress to construct identity in the early modern world.

In all my years of researching and writing about casta painting, I never expected to find these early prototypes, which makes this acquisition thrilling. We will soon be studying the pictures more closely with our team of conservators, as I work to unravel their many intricacies for a forthcoming publication and display in our new museum next year.

During our 39th annual Collectors Committee Weekend (April 26–27, 2025), members of LACMA's Collectors Committee generously helped the museum acquire six works of art spanning a breadth of eras and cultures. Read more about all the acquisitions.

Selected Reading

Escamilla González, Iván, and Paula Mues Orts, “Espacio real, espacio pictórico y poder: vista de la Plaza Mayor de México de Cristóbal de Villalpando.” In La imagen política: XXV Coloquio Internacional de Historia del Arte “Francisco de la Maza,” edited by Cuauhtémoc Medina, 177–204. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2006.

Insaurralde Caballero, Mirta Asunción. “La pintura a inicio del siglo XVIII novohispano: Estudio formal, tecnológico y documental de un grupo de obras y artífices; Los Arellano.” PhD diss., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2018.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. Exh. cat. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1996.

Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Painted in Mexico, 1700–1790: Pinxit Mexici. Exh. cat. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex; New York: DelMonico Books / Prestel, 2017.

Katzew, Ilona, ed. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; New York: DelMonico Books/D.A.P., 2022.

Martínez, María Elena. Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Nygren, Christopher, Ryan McDermott, and Ilona Katzew. Geneologies of Modernity. Podcast, season 2, episode 5. “Picturing Race in Colonial Mexico.” Beatrice Institute and the Collegium Institute, Pittsburgh, 2023. https://genealogiesofmodernity.org/podcast-season-ii-ep-v

Sandoval Villegas, Martha. “El huipil precortesiano y novohispano: transmutaciones simbólicas y estéticas de una prenda indígena.” In Congreso Internacional Imagen y Apariencia, edited by C. de la Peña, M. Pérez M.M., Alberto M.T. Marín, and J.M. González, 1–17. Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 2009.