In 2013, LACMA received a remarkable gift of over 300 pieces of contemporary studio jewelry from South Pasadena collector Lois Boardman and her husband Bob. Sixty-two of these works are currently on view in the exhibition Beyond Bling: Jewelry from the Lois Boardman Collection in the Ahmanson Building through February 5, 2017. All works are documented on the museum's website and in the accompanying book. In the summer of 2015, Jocelyn Wong, a recent Wellesley College graduate and LACMA intern, had the opportunity to work with the Boardman collection, gaining new insight into contemporary jewelry and the artists behind it. Here, Jocelyn has written about one of the jewelers represented in collection, whom she had the chance to meet while in Los Angeles.

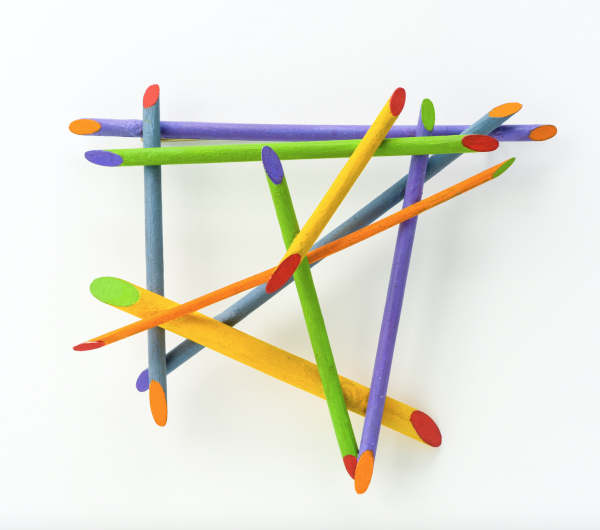

With gloved hands I gingerly held Marjorie Schick’s 1983 brooch, an oblique assemblage of dowel sticks painted in electric hues, a constellation of prismatic spindles evoking all the childish delight of “Pick Up Sticks” play. As a Getty Multicultural Intern working in LACMA’s Decorative Arts and Design department, I conducted in-depth research on Schick and 12 other artists represented in the Boardman collection. I examined the confrontational narratives of Joyce J. Scott’s beaded sculpture necklaces and the pioneering techniques of Stanley Lechtzin’s electroformed pieces. However, I found myself particularly drawn to Schick’s work and her uninhibited experimentation with materials. Rejecting precious metals in favor of craft-store media, Schick created a body of work that challenges established jewelry conventions. She is represented in major museum collections internationally, including Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. I had the privilege of sitting down with Schick to discuss her extensive artistic oeuvre, characterized by playfully wearable works of art.

Born in Illinois, in 1941, Schick still recalls being a four-year old girl sitting in church next to her mother, who wore a “blond muskrat fur coat and a purple feathered hat.” Schick traces her exuberant artistic experimentation with form and color to this kind of early sensorial stimulation, beginning with her mother’s gift of vibrant fabrics and a sewing machine. Schick continued pursuing art, receiving a bachelor’s degree in art education from the University of Wisconsin and later an MFA in jewelry from Indiana University, Bloomington. By the end of her graduate study, Schick had begun experimenting with non-precious materials like iron wire bought from hardware stores. After reading a 1966 article in Art in America about Abstract Expressionist David Smith, Schick wondered “what it would feel like to put a hand or head through a Smith sculpture.” Papier-mâché allowed her to explore this concept. Schick was soon crafting voluminous yet light armlets and collars that pulsated with painted psychedelic patterns. The 1964 invention of acrylic paint, fast-drying compared to oil, allowed Schick to quickly layer bold colors and achieve the spectacle of these pieces. Schick also manipulated papier-mâché into linear forms, wrapping wire from coat hangers with swathes of paper. She called these three-dimensional pieces “drawings-to-wear,” explaining that one “thinks of lines as being on a piece of paper, but mine were suddenly surrounding your shoulders.”

In the early 1980s, Schick continued to explore how linear elements could create dramatic volume with her use of dowel sticks. LACMA’s 1983 brooch is one of Schick’s smaller works from this period; however, it showcases the potential of craft-store birch dowels to create energized fields around the wearer. These sticks are extensions of the physical self. In a 2004 oral history interview for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, she describes seeking to “push at the boundaries of wearability.” By encumbering the wearer with large-scale works, Schick prompts us to consider the interaction between wearer and piece, since the work limits or modifies movement while it is worn. Schick refers to her work as “30-minute jewelry,” pieces to be worn as expressive objects on limited occasions, as opposed to wedding rings or heirloom watches that are examples of “30-year jewelry.” In lectures Schick gave as a faculty member at the University of Kansas, she often referred to a comment that the artist Alberto Giacometti made about Alexander Calder: “What’s this wonderful element in Calder’s work? It’s that element of serious play that makes it what it is.”

This idea of play permeates Schick’s artistic approach. She does not sketch plans, but instead prefers to begin with an idea that evolves as she works. As Schick describes, “Many of the dowel stick pieces would have three or four layers of paint on them before I had arrived at what I thought was going to work on the piece.” A brooch she brought to our meeting had five layers of painted patterns that Schick rejected before arriving at the arabesque swirls of the sixth layer. Schick also brought an armlet, which she insisted I try on. As my hand probed through the obscure opening of the papier-mâché form, I was struck with the realization that Schick not only grapples with form and color but also considers the tactile nature of her pieces. I savored the novel moment of snaking my hand through the armlet opening and the experience of having my movement impacted by the volume of the piece, making it clear to me that studio jewelry is a wearable art form.