At the core of Moholy-Nagy: Future Present, the retrospective of Hungarian-born artist László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) on view at LACMA through June 18, is the Room of the Present, conceived by the artist around 1930 to spotlight the most contemporary artistic production of its time. This multimedia installation demonstrates how Moholy, as an artist avidly engaged in his own moment, was in every sense a proponent of the future.

Through his fervent experimentation with new materials, technologies, and means of representation, Moholy gained early renown in the 1920s; at decade’s end, he was asked to design the Room of the Present by Alexander Dorner, the innovative director of the Provincial Museum in Hannover, Germany. At that time, in the early part of the 20th century, museums of art were still a relatively new idea, elaborations of the older European “cabinets of curiosity.” Dorner was commissioning “atmosphere rooms”: installations of the creative production of various epochs intended to reflect the “flavor” of the art they housed.

Moholy and Dorner made extensive plans for the Room of the Present, recorded in letters and various documents, but they would never see this room physically realized. Lack of funding and increasing artistic censorship due to the rise of National Socialism in Germany prevented the implementation of Moholy’s design at Hannover (both the artist and the museum director would emigrate within several years, eventually settling in the U.S.). In 2009, through the diligence of the researchers Kai-Uwe Hemken and Jakob Gebert, the Room of the Present was at long last constructed based on Moholy and Dorner’s correspondence; it was acquired by the Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands, which loaned it to LACMA on the occasion of Moholy-Nagy: Future Present.

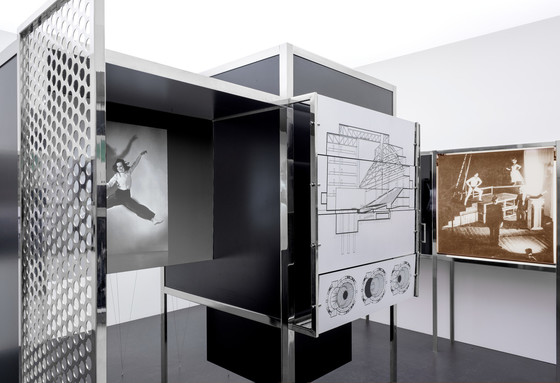

The Room offers a rich glimpse of artistic currents in Germany and elsewhere in Europe during the late 1920s. What did Moholy and Dorner recognize as the art of the very present? On the walls of the room and in its partitioned encasements, we see all kinds of things that extend well beyond the traditional categories of fine art. We see photographs of paintings, sculpture, architecture, dance, and theater; we see photographs of photographs. We watch films of moving things, from transportation to sport to industry.

Moholy’s kinetic Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930) is in the center of the Room; it was designed for theatrical use, with the support of the German electricity firm AEG. As the Light Prop rotates on its base, its metal parts shift while it projects multicolored lighting effects. Throughout the Room are more examples of industrial manufacturing combined using artistic invention: a curving wall made up of lengths of glass; a motorized belt, or “endless band,” of illuminated images, operable at the push of a button; shiny-surfaced, nickel-plated lamps and fixtures designed at the Bauhaus to be mass-produced and thus affordable for the modern home.

The Room of the Present is not made up of unique objects. The present, for Moholy and Dorner, was all about new things that could be reproduced and spread through technology. Photography is everywhere in the Room; Moholy embraced this nascent creative medium as a “new vision” that extended art’s reach to an ever-greater public. Today, in the age of the Internet, our minds inhabit a space, like Moholy’s, of images, images, images, and of the fast transmission of ideas. Today, using our smart phones, we make, upload, and access others’ creative acts nearly instantaneously. We escape our physical limits, our confinement to familiar interior spaces, through what we can access online.

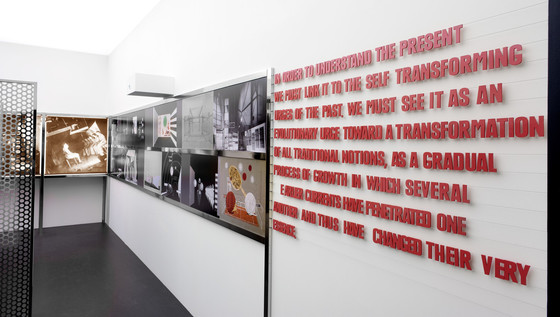

Our present was, for Moholy, the future. Many of the images in the Room of the Present are back-lit, attractive like screens, but nothing is “high speed” by our standards. Along one section of wall, there are three-dimensional letters assembled across wires that reflect the printing processes of that distant time when graphic designers used moveable type. The text spelled out by the letters is a quotation from Dorner’s writings, chosen by Hemken and Gebert for the Room:

In order to understand the present we must link it to the self-transforming urges of the past. We must see it as an evolutionary urge toward a transformation of all traditional notions, as a gradual process of growth in which several earlier currents have penetrated one another and thus have changed their very essence.

It was unusual in the early 20th century for a museum director like Dorner to put the most contemporary of creative production on public display. In contrast, we now assume museums will offer cutting-edge multimedia environments like the one Moholy envisioned with Dorner. At museums today, we convene (smart phones in our pockets) to encounter spaces that expand the parameters of art, where the rooms of the past are also present, and sometimes look close to the future.

Moholy-Nagy: Future Present is on view in the Art of the Americas Building through June 18, 2017. For further information on the Room of the Present, see LACMA associate curator Jennifer King’s essay “Back to the Present: Moholy-Nagy’s Exhibition Designs” in the exhibition catalogue.