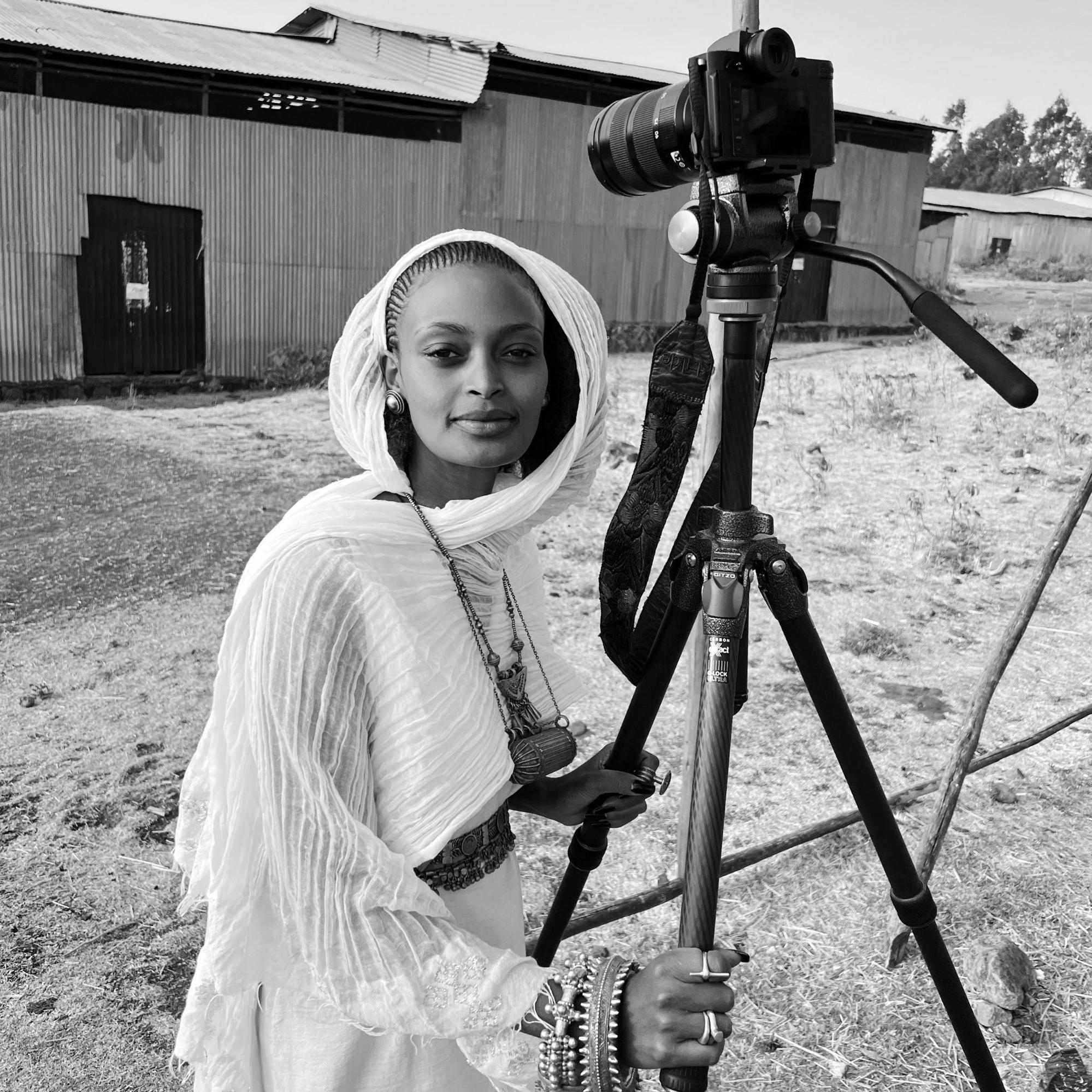

Cactoid Labs’ curator and co-founder, Lady Cactoid, recently sat down with Kiya Tadele, the creative director of the artist collective Yatreda to explore the work they are creating in dialogue with LACMA’s permanent collection for the project Remembrance of Things Future, curated and engineered by the experimental blockchain consultancy Cactoid Labs.

Building upon LACMA’s historic engagements with art and technology, Remembrance of Things Future is an invitation to travel via the blockchain back in time through the museum’s encyclopedic collection. Utilizing the mediums of film and experimental motion-based photography, Yatreda, alongside other pioneering artists, has been invited to select objects from LACMA and make new digital editions inspired by the museum’s holdings. Released on the blockchain in phases, a percentage of proceeds from these limited Remembrance of Things Future digital editions go to support LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. More information on this project can be found at lacma.cactoidlabs.io.

Hi, Kiya! Our previous conversation traversed the foundations of your research-based practice. Here, I’d love to turn to the stunning works you created for Remembrance of Things Future, in response to a historic 13th-century bronze Ethiopian cross in LACMA’s permanent collection. What drew you to this object and how did this sacred piece ultimately give way to your new pieces? Can you tell us about the connection between the cross and the Ethiopian ritual of Meskel, and touch on the narratives you are addressing in each of the four works?

When I saw the cross in LACMA's collection, I recognized something that is everywhere in Ethiopian life, because Christianity came to us in the 4th century. In fact, Ethiopia was one of the first regions in the world to officially adopt Christianity. You go to Ethiopia, you will see the cross in everything. Woven into traditional clothes, in jewelry, every believer wearing one, in the architecture, even in countryside tattoos. But seeing it in a museum made me think deeper about how the story started

Every year in Ethiopia we celebrate Meskel, an annual tradition where we honor the finding of the True Cross. (Meskel means cross in Amharic.) The legend dates to the 4th century when Empress Eleni (known as Empress Helena in the West, the mother of the Emperor Constantine) received a divine vision that led her to discover the hiding place of three crosses used at the crucifixion of Jesus. The story goes that Empress Eleni’s vision instructed her to light a demera (large bonfire) and follow the smoke to uncover the hidden relic of the True Cross, buried beneath the earth for centuries. Local legend says that a piece of the cross discovered by Eleni remains in Ethiopia today, at Gishen Mariam Monastery, a remote church in the northern highlands. The celebration today can involve hundreds of people gathering around the demera together. But filming people celebrating is not the art for me. I wanted to go to the origin. To Empress Eleni's divine vision. The art I wanted to make was about capturing that vision itself.

Here's how I approached it: there are four artworks in this series, but you could consider the LACMA cross as the fifth. We move from pure vision to physical object, from formless to form.

The first work is a 16-minute film called Revelation of the Empress, which is about vision, something that exists only in the mind. It is formless but real. Then comes the three shorter works. Path of the Demera explores the idea of Empress Eleni’s vision taking the form of the smoke she must follow. With Unearthing the Relic, the smoke leads to finding a physical piece of the wooden cross buried in earth, becoming more solid but still lost in time. Finally, Guiding Light shows the metal cross as we use it today, strong and permanent, to carry our faith forward.

So we made a kind of prequel to the museum object. We built a five-meter demera using inherited techniques and set it on fire, just as Eleni did in the legend. What drew me was this: the cross isn't just a relic. It's a living symbol that connects ancient prophecy to how we practice faith today. By going back to the vision that started it all, we show how legends breathe through time, through our hands, into tomorrow.

Revelation of the Empress, the film you created here, is your longest work to date. Can you tell us about the production process?

I do understand this giant burning cross bonfire can be shocking to audiences outside Ethiopia. But for us, we are used to it. Communities all over the country build them annually for Meskel, to light them on fire. We had only one shot to get this right. Imagine how long it took to build with all that wood. After we built the set, we practiced many times in the daylight, but I told the actress Lydia there will be no cut, no movie magic here, just one take. No special effects on the computer. If the fire is going to jump into you, just toss the torch into the bonfire and naturally walk back, staying in character. If wind or smoke comes in front of your face, act like that's part of it.

We had hidden marks made out of stones on the ground. Lydia would begin out of frame, go to the first marker, then the second, spending time in each place, while I'm calling out the numbers to direct her. But the actress had her own responsibility outside my control. Inside the pyre was full of incense, and we didn't know which way it would blow. So she really embodied Empress Eleni, following the incense where it led.

We selected the location for its horizon line and proximity to local craftsmen. Mamush, the man who constructs the demera every year in this village, led the building of ours for the filming. We notified the kebele (local district) office for permission. We had a safety water truck on standby, and many people off-camera with buckets for the water, and also holding branches with leaves. That’s actually the best way to stop a potential grass fire, sweeping it out early. We also wet the ground around the pyre before the shoot.

Is there an element of chance at play in this work? For instance, I am struck by the enigmatic role of environmental forces such as wind, smoke, and fog in your films. Are these elements something you bring to amplify narratives in post-production, or do you encounter them in situ naturally during the making?

About chance and environmental forces… They are central to this artwork. The fire, wind, and incense smoke, these are not post-production effects. They’re fate’s hand in the artwork. We can control many things, but nature adds the magic we could never plan. That's what makes each piece alive.

LACMA mounted a recent exhibition titled Ritual Expression: African Adornment from the Permanent Collection, which shone a light on a variety of textile traditions in Africa. I am always mesmerized by the dresses and jewelry you and your actors wear. Where do these pieces come from, and are there other three-dimensional objects of significance with interesting backstories that you can speak to ?

My inspiration comes from historic paintings and photographs from times when there was no plastic, no chemical dyes. When everything was handmade from cotton, metal, natural materials. Even today, I use these same materials. They're still around, but you have to really search for them. It's very classic and timeless.

To relate to this cross in the LACMA collection, we looked at the broader region during the 13th century. North Africa and the Middle East, where the stories of the True Cross were shared across cultures. Empress Eleni is Helena of Constantinople in the wider Christian tradition. In those days, everything was hand-spun cotton, metalwork hammered by skilled craftsmen. So we sourced traditional hand-woven cotton from weavers who still use the old techniques, making the dress by hand.

The jewelry tells stories of ancient trade routes across the Red Sea. When you look closely, you see influences. Designs that are shared with coptic patterns in Egypt, metal beadwork from Arabia, some details that remind us of India, styles that traveled from Byzantium. Ethiopia was never isolated; we were always part of this cultural exchange.

What makes me happy is that these objects carry memory. When our actors wear these pieces, they're not just costumes. They’re connecting to centuries of hands that made and blessed them. I believe that is part of the weight you feel when looking at the artwork.

Los Angeles has one of the most vibrant Ethiopian diasporic communities in the world, and the heart of Little Ethiopia is located near to LACMA. Thus the beauty and spiritual dimension of your works—which read as mysterious spell-binding moments captured magically by the camera—resonate on a special local level here. In closing perhaps you can speak to the emotions you hope to engage with your audience through these new creations.

Knowing that Little Ethiopia is so close to LACMA makes this project even more meaningful. I want to say it was also an honor to work with you, Lady Cactoid. Our great Ethiopian stories and folktales belong alongside the great American master artists. For Ethiopians, especially those far from home, I hope they feel that deep tizita. That nostalgic pull that sings to them, "this is who we are." But also pride. Our stories deserve to be here. We should know how unique and special our place in history is. Young Ethiopians growing up in L.A. or Addis should see that their heritage isn't just something in dusty books. It's forever evolving and creating new art for new times.

For those discovering Ethiopian culture, I want them to feel what I felt as a child when my mother told me these stories, that sense of mystery, of something ancient but alive. Museums and digital art are both public spaces where cultures meet and speak to each other. But we Ethiopians also carry our museums in our hearts. What I hope these works do is bridge those two spaces. The formal institution and the living memory.