The myth of Cupid and Psyche is a touching and relatable story, including elements of forbidden love, magic, heartbreak, jealousy, secrets, a quest, and, of course, girl power. It's no secret that the Romans had a flair for the dramatic and though their tales often revolve around immortal beings, they express deeply human concepts, which have cemented their relevance across time and culture and their representation in virtually every medium of artistic expression. The pervasive myth of Cupid and Psyche is no exception, with art spanning centuries in museums around the world, including LACMA (some on view soon in the David Geffen Galleries). Different renditions of the story emphasize various motifs, influenced by culture and history, but always highlight themes of love felt and lost that still connect with audiences today.

The myth of Cupid and Psyche appeared first as the centerpiece of the second-century novel The Golden Ass by Apuleius. It chronicles the journey of a young princess Psyche (Greek for Soul) who is so beautiful that she is worshiped as Venus. The goddess Venus, in a fit of jealousy, sends her son Cupid to strike Psyche with one of his arrows, cursing her to fall in love with a hideous beast. Instead, captivated by Psyche’s beauty, Cupid accidentally scratches himself and falls madly in love with the mortal. Though Cupid tries to conceal his identity to protect his new wife, a series of trials and tribulations for Psyche soon follow, including jealous sisters, invisible servants, a leaky oil lamp, and an impossible quest to the underworld. At the end of the story Psyche is bestowed immortality by Jupiter in order to spend the rest of her life with Cupid. Soon after, their daughter Pleasure is born.

The tapestry Psyche Contemplating Cupid (1792) by Michel-Henri Cozette and Clément Belle depicts the moment Psyche breaks her vow to Cupid, giving in to her curiosity, and discovers her husband's true identity. Here, a sneaky sense of optimism radiates from Psyche as she peers down on her sleeping husband, who she realizes is the god of love. A hold-your-breath, too-good-to-be-true feeling emanates from the scene, but the other shoe is waiting to drop: we know that after Psyche will wake him by spilling a drop of oil from her lamp, Cupid will take flight, leaving her forever.

In this depiction, Psyche is not wearing ancient Roman clothing, but is dressed in an elaborate late-18th-century European gown. In fact, the entire scene takes place in a contemporaneous French bedroom, adding a layer of relatability for the viewer. This 12-foot tapestry not only reflects the wealth of those who owned it, but immerses the viewer in the moment before Psyche’s fall from grace.

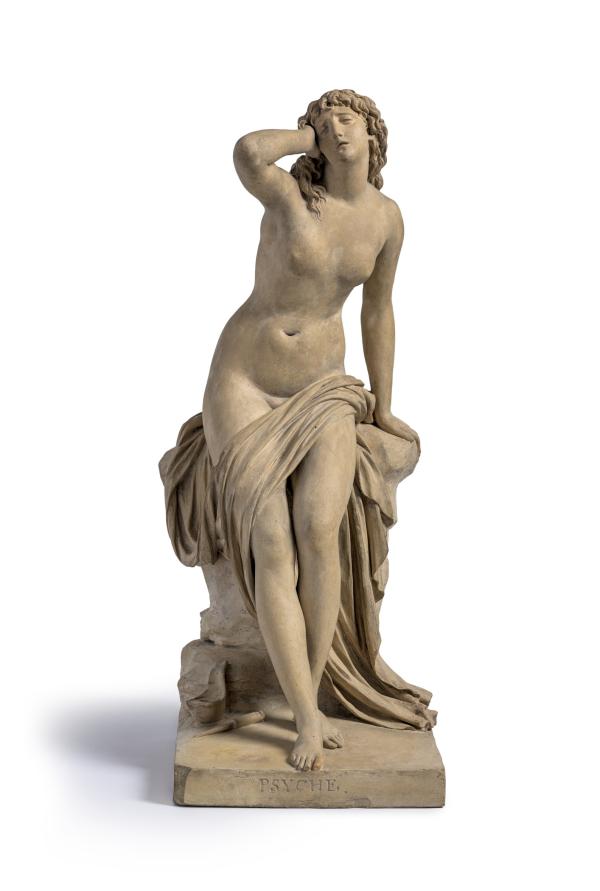

Psyche Abandoned (1796) by Augustin Pajou presents Psyche alone, looking more devastated than wistful as she reclines on a rock, head in hand. At this point, Psyche embodies the myth’s themes of loneliness and lost love. After breaking the promise she made to her husband, she is once again alone, alienated and back among mortals. This freestanding sculpture makes Psyche’s isolation physical, with empty space surrounding it on every side. As Psyche stares into the unknown, devoid of color or setting, the viewer is left contextless, their only clue being the distraught look on her face. Though this sculpture radiates great sadness, to those who know the story it carries the theme of channeling great loss into action: it marks the beginning of Psyche's quest, a series of impossible tasks given to her by Venus in order to win back Cupid.

This painting by Jean Pierre Saint-Ours is a preparatory sketch titled The Reunion of Cupid and Psyche and represents the conclusion of the myth. After completing Venus's impossible set of tasks, culminating in an epic voyage to the underworld, Psyche is granted the gift of immortality and may be with Cupid forever. Here, the lovers stare longingly into each other's eyes, their divine connection highlighted by their setting amongst the clouds and by the doves to their right. A powerful glow radiates from the painting as Psyche’s isolation, sadness, and longing for Cupid have come to a close, as resonant for a contemporary rom-com–loving audience as it may have been to a viewer in 1793.