Ed Moses: Drawings from the 1960s and 70s, closing next month, marks nearly 40 years since the artist's last solo exhibition at LACMA. In 1976, Ed Moses: New Paintings, a two-gallery installation organized by LACMA curator Stephanie Barron, featured Moses’s red monochromatic “abstract” and “cubist” works on canvas. That same year UCLA’s Wight Gallery mounted a survey of Moses’s drawings from 1958 to 1976. In retrospect, the confluence of the two exhibitions marked a significant transitional moment in Moses’s career. While drawing was prominent in his work from the 1960s and early 1970s, by the mid-1970s Moses turned primarily to paint on canvas. As he said at the time: “The earlier drawings are metaphors for painting, while my later drawings are pictures of painting ideas,” signaling a shift away from drawing for drawing’s sake and toward the notion of drawing as preparatory to painting.

The exhibiton currently on view revisits much of the same work presented at the Wight Gallery but with the advantage of hindsight. While widely known for his abstract, large-scale improvisations with paint on canvas, Moses spent his early years as an “explorer” or “discoverer” (terms he prefers to “artist”), wielding pencils, stencils, and rulers to make or construct hundreds of drawings that have been rarely seen or studied. This fact may come as surprising, especially knowing that the early drawings were featured in three solo shows at the now famed Ferus Gallery in 1961, 1963, and 1964, when Los Angeles was just emerging as a center of art making. During this period, Moses (along with Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, and others) represented the spirit of a new generation.

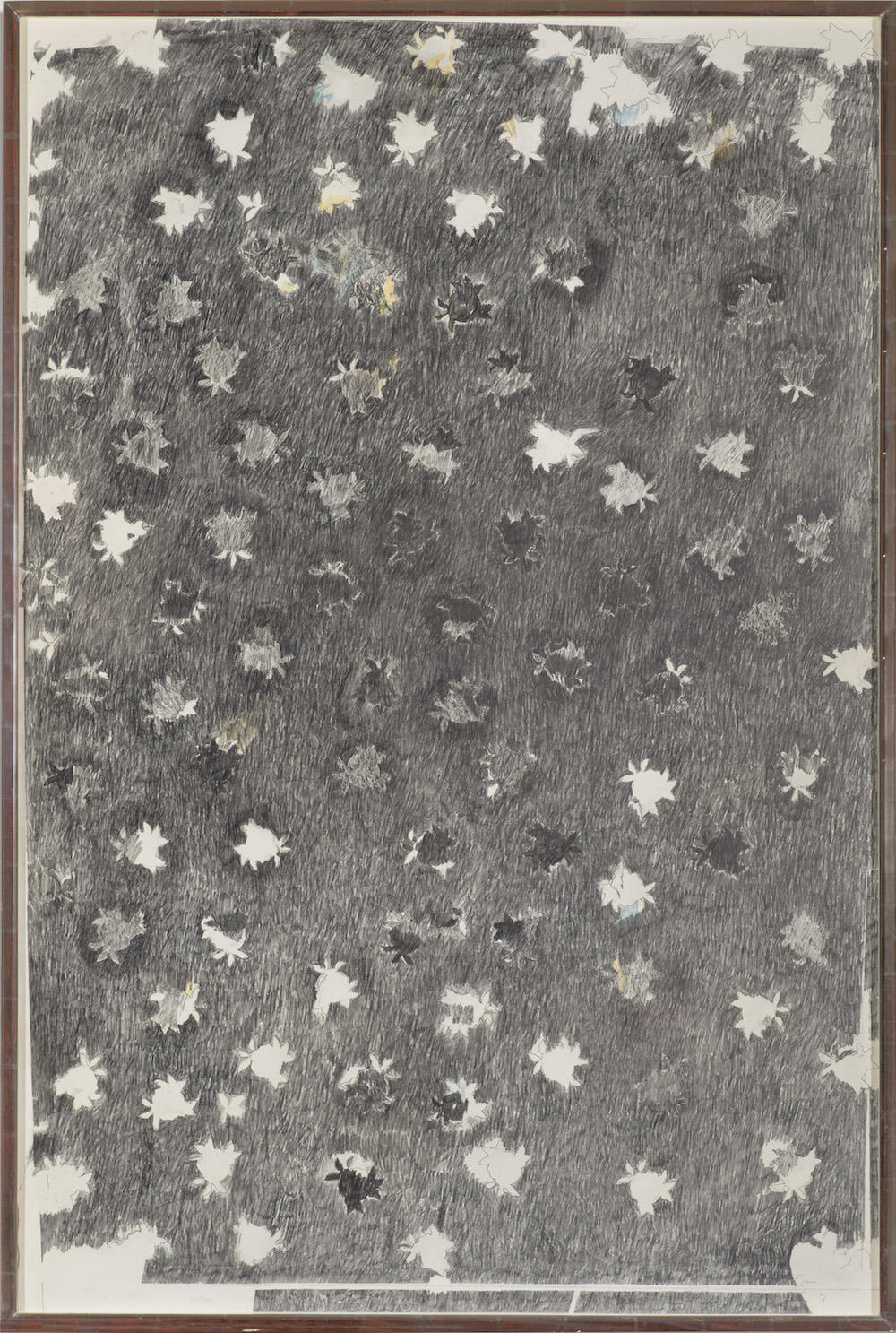

Moses’s drawings of roses and lilies, grids and squares, and Navajo-inspired patterns engaged directly with prevailing movements of the time—Neo-Dada, Pop, Minimal, and Process art—as well as with movements of the past, namely the geometric abstractions of Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich. His series of Rose Drawings (1963), for example, were derived from a pattern of roses on a Mexican oilcloth he found in Tijuana. According to Moses, he made stencils of the rosebuds and blossoms, traced them regularly across the surface, and then compulsively filled in the ground in between with graphite. His drawings beginning in the mid-1960s were made with the same obsessive and repetitive marks in graphite but applied to the pattern of a more minimal grid. The diagonal grids in Moses’s work, which characterize both his drawings and paintings of the mid-1970s, were derived in part from patterns found in Navajo blankets that were introduced to him by fellow artist Tony Berlant. Moses felt the textile patterns represented an alternative to western European forms of abstraction but also may have influenced his turn to canvas as a support.

Influenced in part by his experience as a technical illustrator working for Douglas Aircraft in the 1950s and in part by the ethos of Abstract Expressionism that predominated his student years, Moses devised his own graphic language of scribbled marks and mechanical lines that embody an uncomfortable but provocative union of expressionism with system and rigor. His use of stencils and rulers, for example, allowed him to lay the groundwork in a nearly automatic way, providing a structure for meaningful accidents and invention. When engaged in creating this foundation, Moses said he “wasn’t thinking about the arrangement but was fascinated with things as they would appear. It’s the fascination of discovery by marking.”

What became apparent after careful study of the early drawings is how fundamental they were to Moses’s subsequent and substantial body of paintings on canvas. Executed with paint rather than graphite, the paintings (like the grid works featured in LACMA’s 1976 exhibition) were often executed with the same tools and methods of chance and repetition that characterized his drawings. While Moses has since become internationally renowned for his abstract paintings, I would like to suggest—twisting Moses’s own words—that his later paintings are actually pictures of drawing ideas formulated in the 1960s and early 1970s.

A version of this article originally appeared in the spring 2015 (volume 9, issue 2) of LACMA’s Insider.