The collaborative work of Pouya Afshar and [P]ART Collective is featured in Islamic Art Now, Part 2: Contemporary Art of the Middle East, the second installment of a two-part exhibition at LACMA drawing from recent contemporary acquisitions by our Islamic Art department.

The video Sohrab's Blood, from the Rostam in Wonderland series, is a collaboration between [P]ART Collective and Sooriland Studios and is among the exhibition's innovative reflections on past and present Islamic culture. The series is based on Rostam, the mythical hero of the Book of Kings (Shahnama), a thousand-year-old work by the Iranian poet Ferdowsi. Sohrab's Blood takes place just after Rostam unknowingly encounters and kills his son Sohrab in combat, and in this video, Rostam encounters (and tries to reconcile with) the world of 21st-century Iran.

I spoke with Afshar to discover the origins and motivations behind his project.

Tell us how you and Soroush Rezaee worked together to create the Rostam in Wonderland series.

After my studies at CalArts and UCLA in animation, I started visiting Iran more often. I became more and more interested in Persian mythology and storytelling rituals. In a sense, nostalgia was carrying me toward those roots. I started examining different scripts and visual works revolving around Persian mythology, especially the Shahnama.

On one of these trips to Iran, I met Soroush. At the time, he was creating these short, simple, and fun animated videos. After I returned to U.S., I started planning for the series and asked him to collaborate with [P]ART Collective. I came up with the core of the project and several ideas for storylines as well as some character design; Soroush then made those stories his and refined them into what he does best with satire.

![Pouya Afshar and Soroush Rezaee, collaboration between [P]ART Collective and Sooriland, video still from Rostam in Wonderland, five episodes, 2012–2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the artist, © Pouya Afshar](/sites/default/files/attachments/M.2015.68.1-.3%203.jpg)

![Pouya Afshar and Soroush Rezaee, collaboration between [P]ART Collective and Sooriland, video still from Rostam in Wonderland, five episodes, 2012–2014, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the artist, © Pouya Afshar](/sites/default/files/attachments/M.2015.68.1-.3%202.jpg)

Did you have an audience in mind when making this piece? Have you noticed different reactions between audiences who are familiar with the Shahnama and those who aren’t?

Our target audience was young Iranian adults—the majority of people in Iran. Although older generations in Iran are becoming more familiar with internet technology, they are not as involved in social media movements.

In the beginning, several viewers claimed that we were making fun of Rostam. They were either people who were not familiar with Persian mythology and history, or pan-Iranians outside of Iran who were disconnected from contemporary Iran. Both groups complained about using Rostam in satire. After a few episodes aired, these complaints toned down. When the last episode (which deals with racism against Afghans in Iran) was aired, the majority [of our viewers] were in tune with our version of Rostam being a tool for cause-related change.

There are thematic similarities between Sohrab's Blood and Siamek Filizadeh's Rostam II returns at age of 30 having been brought up abroad, which is also featured in Islamic Art Now, Part 2. With tongue in cheek, both pieces expose Rostam to the absurdity of contemporary culture. For you, what was the inspiration to take this approach?

Rostam, as we know, is not a real character. He is a man-made idol. Ferdowsi, the author of the Shahnama, chose Rostam as a vehicle to transport the readers from myth to epic. He uses him as the main hero of the poem, but Rostam is not his invention. He was created collectively by Iranian storytelling. Therefore, every Iranian can relate to this character. We [Soroush and I] believed that Rostam had the potential to be a personality people could correlate with, especially when placed within their universe, dealing with their modern problems.

By using the series as a whole to orchestrate our ideas, we were able to keep up with the fast pace of social media and people’s short attention spans. You might ask, why not TV? Because this way, people could watch, re-watch, comment, re-comment, and start a dialogue about the issues mentioned in the series.

Your allusions to Rostam in other bodies of work, particularly your Book of Kings series, offer a starkly different tone—one that exposes the darkness of his warrior lifestyle. Why was it important to you to address this character in opposite ways?

I had to examine him first. I needed to live with him, talk to him, and feel with him as an imaginary friend, before making him believable to an audience that is neither familiar with the Shahnama nor contemporary art.

Our take on Rostam has a very vulnerable sensation to it. He is a character restricted by his physical capabilities. He is often involved in situations and storylines that are rigged in resolution.

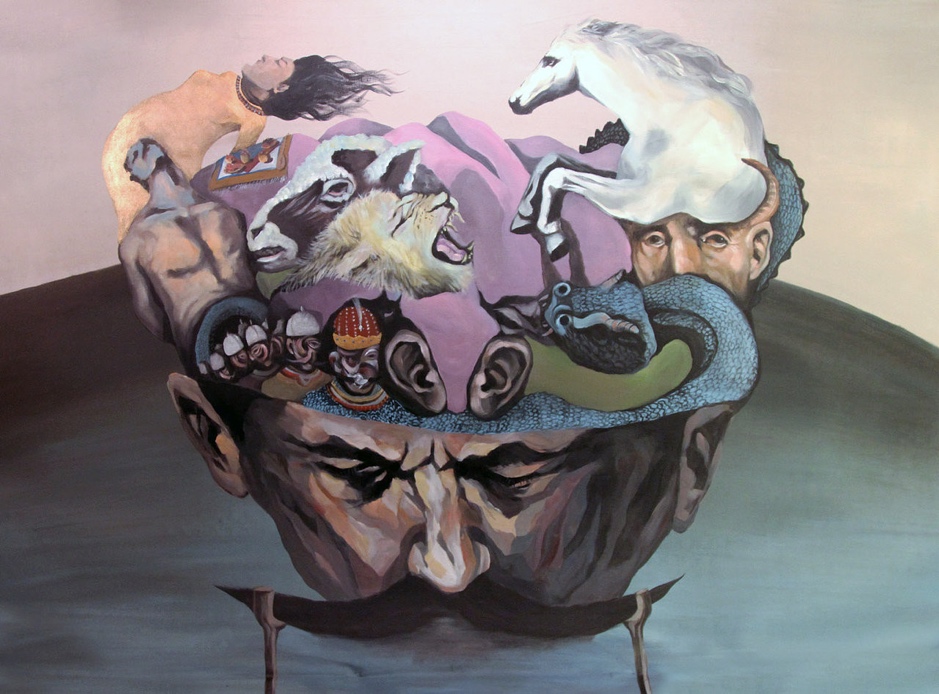

Prior to my series Book of Kings, I did another painting series called Pahlevan, which deals with the heroes of the Shahnama. The Rostam in that series is a warrior, and features those qualities more than the qualities of a hero. But he is known as a hero because people like to be warriors themselves, and to not give up—whether they are facing the army of “Turan” and dealing with “The White Demon” [as the fictional Rostam does], or facing sanctions on medicine and the economic hardships of 21st-century Iran.

Islamic Art Now, Part 2: Contemporary Art of the Middle East, is ongoing in the Ahmanson Building, Level 4.