Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, now on view at LACMA through August 3, 2025, finds aesthetic connections among 60 artists working in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The exhibition and its catalogue are among the first to examine nearly a quarter century of production by Black artists.

Curator Dhyandra Lawson asked four artists to respond to written questions about their work and the diasporic experiences they are connected to. The artists’ respective practices center on photography, the most pervasive mode of representation today. In this excerpt, Frida Orupabo reflects on her work Untitled (sources unknown except Shadman Shahid [bottom left]) (2019), which is featured in the exhibition. The full interview can be found in the Imagining Black Diasporas exhibition catalogue.

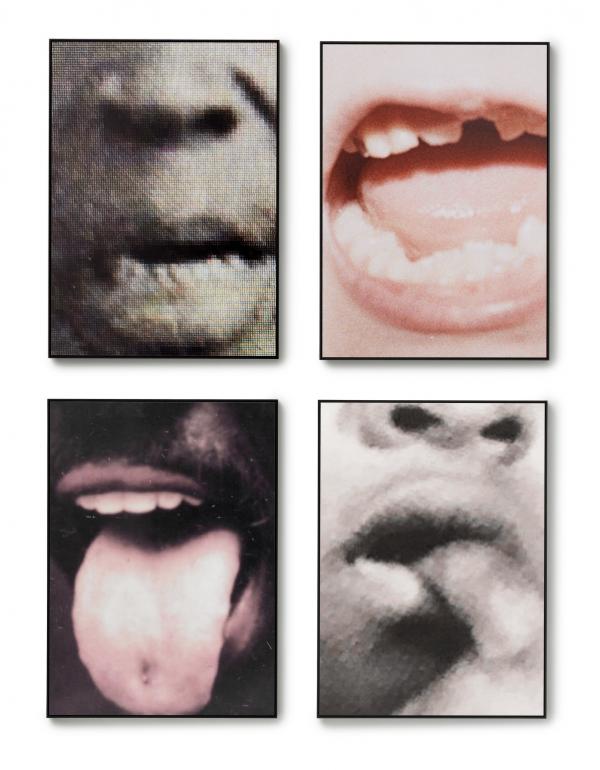

Dhyandra Lawson: Untitled (sources unknown except Shadman Shahid [bottom left]) presents four mouths mid-utterance installed in a quadrant. The pictures of the mouths anticipate sound or the expression of words, but as images they are silent. Do you trust images to convey meaning more than language? How so, or why?

Frida Orupabo: I don’t know if I trust images to convey meaning more than language per se. It just happens to be my preferred form of communication. I’ve never been good or confident when it comes to expressing myself through text or speech. I think this fear started in (pre)school. There were so many rules, and so many pitfalls, so easy to get stuck, while images are like a hiding place. It can be crystal clear and woolly at the same time, like a secret language.

There’s this interview where David Hammons talks about his body prints. I’ve mentioned this before, but it’s so linked to my own feelings toward the use of images (on another level than what I just mentioned). He’s saying that the prints happened because he didn’t trust the images that he made to be truly what he wanted to represent. And that by using the body he felt that he was going to have the truth whether he wanted it or not. He said, It is going to be myself and it is going to be us. It’s a safeguard protecting me from being who I might think that I am by doing body prints—it’s telling me exactly who I am and who we are. And this is precisely how I’ve always felt about the image. It’s a safeguard that guides me toward a “truth.” It’s a direct depiction of a face, a body. A true depiction of who I am, or who we are.

DL: Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics examines contemporary diasporic aesthetics and experiences. “Distance” emerges as a theme throughout the exhibition—the distance between where one is and where one’s ancestors came from—but also the psychological and emotional dissonance people may experience in globalized 21st-century societies.

You were born in Sarpsborg to a Norwegian mother and a Nigerian father. In past interviews, you’ve described how your mother and grandmother raised you. You exhibit internationally and are represented by galleries in Europe and South Africa. Your practice of researching and sourcing images online takes you to archives from different times and places. Do you relate to diasporic experiences of movement, migration, or alienation? How might diasporic themes figure aesthetically into your art practice?

![Frida Orupabo, Untitled (Sources unknown except Shadman Shahid [bottom left]), 2019, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Burton Aaron, © Frida Orupabo, courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin/Stockholm/Mexico City; photo: Gerhard Kassner](https://unframed.lacma.org/sites/default/files/attachments/M.2020.265.1.1-.4_FO.jpg)

FO: This is a vital part of my work—the past, the here and now, as well as the future and how they all are intertwined. Things that have happened in the past are still with us, and if we pay attention, it will give us a clearer understanding of the situation we’re in. I’m trying to show this connectedness through my work—to understand the history of slavery, for instance, and its ongoing legacies and how it affects how we see. It’s a way of seeing or understanding history that was never taught to me. It’s about trying to find a way “out”—a different way of seeing and interpreting history, identities, and so on. My work builds on other artists’ and thinkers’ works, consciously and unconsciously. I believe my hunger for images is a result of growing up in a culture (like so many others) that lacked (positive) representation of Black people. We were nowhere to be seen except in (more often than not) stereotypical portrayals. The colonial archive is deeply rooted in my work. Though the images were taken to dehumanize, objectify, control, I believe that these archives also show forms of resistance—through the gaze, the position of the body, etc. But it’s through the practice of distorting, extracting, adding, and manipulating that I feel I manage to construct different narratives and identities that speak to a complex reality and history—to shed light on our multiple identities, the intersection between them, and the different, sometimes conflicting narratives that run side by side.

DL: You have practiced collage for over a decade. The practice entails reassembling discrete images into new compositions. Can you please describe the significance of collage for you. Is the act of reassembly an act of healing or repair?

FO: I’ve already touched on it briefly, but the collage is important to me because it makes possible another way of seeing and imagining. I like how quickly one can switch a meaning or an expression through the use of collage—by adding, removing or manipulating images or objects. I like that different pieces that don’t belong to one another can make up a whole—a new narrative that fits my own reality. For me, it’s the medium I’m most comfortable with, and which makes the most sense in terms of what I want to accomplish with my work.

Further, I think the act of reassembly can be an act of both healing and repair. But it’s not given that these two follow one another. You can repair something, but it doesn’t mean that the aspect of healing is present. But for me, working with the visuals has been linked to both things—not always, but most times. Personally, the work has been and still feels like a necessity, something I have to do. I often used the word sane—“I do it to stay sane.” Maybe that’s a bit over the top, but I’m still sticking to it, because I still believe that the work of reassembling is vital for my sanity—which in many ways is linked to the work of healing and repairing, which reminds me of bell hooks’s thoughts on why she came to theory. For her, it was also linked to a need for healing and repairing and to a deep wish of wanting to understand herself and the world around her.