Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, now on view at LACMA through August 3, 2025, finds aesthetic connections among 60 artists working in Africa, Europe, and the Americas. The exhibition and its catalogue are among the first to examine nearly a quarter century of production by Black artists.

Curator Dhyandra Lawson asked four artists to respond to written questions about their work and the diasporic experiences they are connected to. The artists’ respective practices center on photography, the most pervasive mode of representation today. In this excerpt, Widline Cadet reflects on her work Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1) (2019), which is featured in the exhibition. The full interview can be found in the Imagining Black Diasporas exhibition catalogue.

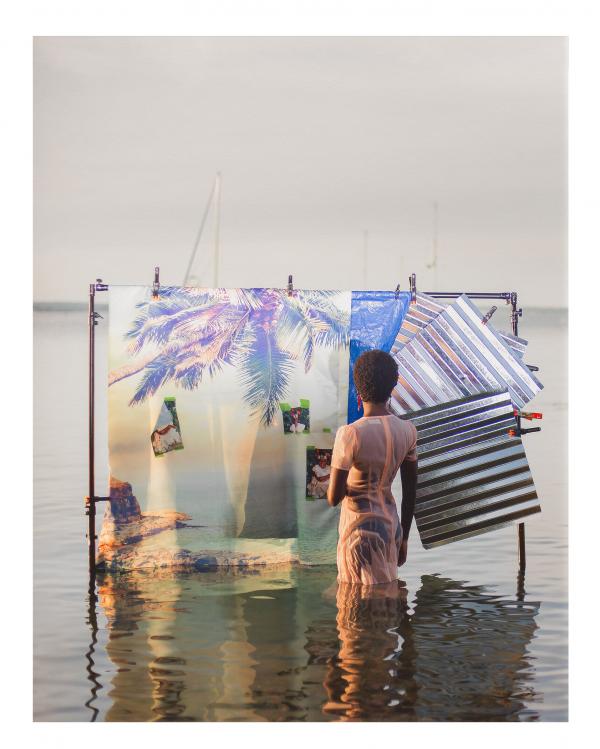

Dhyandra Lawson: In Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1), you portray yourself in the ocean, turned away from the viewer, facing a backdrop with palm trees, family pictures, and the horizon in the background. Can you please speak to the significance of the work’s subtitle, Ritual (Dis)Appearance, in relation to how you composed the image?

Widline Cadet: I made the work long before the title became a factor. During the construction of the image, I was thinking about what to me felt like rituals that I, members of my family, and friends were going through as a result of our immigration/migration to the United States. For me, these rituals consisted of survival methods and things like learning English and slowly having that become my first language, going to school and adapting culturally to my environment in New York City, and so on. All of those felt like rituals of migration that are necessary, but as a result were changing my being and causing other parts of myself to shift and disappear.

I was also thinking about the idea of memory in relation to this. How the act of me immigrating/migrating is in and of itself an act of disappearance. How long before any trace of myself and my family disappears completely from my birth country, people’s memories, the landscape, as well as the historical records? And what happens then? While I didn’t necessarily have the verbal language when I was making the image, looking at it now, maybe part of it is that I wanted to create a space in the photograph where all the things and versions of myself that disappear in the process of these rituals can exist.

DL: Do you consider the work a self-portrait?

WC: Yes, definitely

DL: There is a sense of both intimacy and distance in the work. Can you describe this tension as it relates to your experience and/or practice?

WC: I think the sense of distance and intimacy enters my work from a few different places. A large part of my practice includes making work about things, places, and people I don’t necessarily have tangible knowledge of or open access to. That lack in some ways can be seen and translated as distance. The intimacy part comes in when I incorporate my own experience, and that’s something I know and can speak to intimately without any doubt. That, too, is reflected in the work.

DL: Seremoni Disparisyon #1 (Ritual [Dis]Appearance #1) features the landscape prominently. Not only are you standing in the water, but the backdrop reinforces a coastal scene. Images of the natural environment appear in works throughout your series Ritual (Dis)Appearance (2017–ongoing) and Home Bodies (2013–ongoing). Can you describe the significance of landscape to your practice?

WC: I think about land a lot. My grandparents on both sides of my family owned and cultivated a lot of land, and the land was handed down to my parents’ generation. To me, the idea of owning land in Haiti functions as a signifier of ancestral belonging and wealth, but my siblings and I don’t have access to land ownership—either in Haiti or the U.S.—largely as a result of our migration, among other factors. And so the landscape then becomes important in my work as a means of creating a space where I can be physically rooted in a fictional and maybe aspirational land of my own, and can thus start to feel a sense of belonging.