Guillermo del Toro considers his collections to be essential sources of nourishment and inspiration. He has accumulated hundreds of paintings, drawings, sculptures, books, and specimens over many years, pursuing longstanding passions and making new discoveries. The collection grows organically but not haphazardly, with del Toro fully involved in arranging and maintaining it. Indeed, the filmmaker’s collections are essential to his working process—they constitute his environment and, grouped into thematic libraries, stand for the various genres and subgenres he wanders among as a storyteller.

Del Toro’s notebooks, collections, and domestic environment point to the curatorial aspects of his approach to filmmaking. On one level, he carefully constructs and stages his films in the manner of an exhibition. On another level, he fills their plots with commentaries about the social, psychological, and spiritual power of objects. For del Toro, collecting is a fruitful creative activity—one he pursues with awareness of historic precedents and with his own distinct intentions. In Guillermo del Toro: At Home with Monsters, on view at LACMA from August 1 through November 27, del Toro demonstrates the energizing effects of cross-pollination among genres, categories, and disciplines.

Del Toro’s approach to collecting draws upon two traditions, which evolved to serve different social and individual needs: the museum or public repository of artworks, and the cabinet of curiosities or private accumulation of oddities. The idea of the museum as we know it today emerged in the 18th century, concurrent with the Enlightenment. Manifestations of the era’s encyclopedic ambitions and taste for the exotic, museums have long been associated with taxonomies, connoisseurship, and instruction.

The museum’s 16th-century predecessors—known as cabinets of curiosities—were more permeable than museums: magical, messy accumulations of natural and human-made artifacts assembled by individuals who were enthusiasts as much as academics. Objects in cabinets of curiosities were valued for their talismanic properties and as evidence of the world’s strangest phenomena. Cabinets of curiosities were dynamic collections that were often portable, subject to rearrangement and use, and imbued with latent super-natural properties.

The distinction between these two types of collections survived into the 20th and 21st centuries, perhaps becoming even starker. Public collections have become highly professionalized; private collections proliferate at all economic levels. Both types of collections—public and private—are powerful engines of consumption and production, as well as frameworks for knowledge. For evidence, we have only to look at how behavior on the Internet, a virtual repository for information and interpretation, revives the Enlightenment fantasy of total, encyclopedic categorization of all things and all ideas, while it also nourishes the fixation on the random and the strange.

That being the case, it is important to recognize especially inspiring and provocative collectors such as del Toro, whose approach spans private and public, high and low, historic and contemporary, sacred and profane. Avowedly obsessive, del Toro maintains several house-scale cabinets of curiosities as sanctuaries and workplaces. Chief among them is Bleak House, located in the outer suburbs of Los Angeles. Like Mr. John Jarndyce’s residence of the same name in Dickens’s novel, del Toro’s private sanctum is:

“ . . . one of those delightfully irregular houses where you go up and down steps out of one room into another, and where you come upon more rooms when you think you have seen all there are, and where there is a bountiful provision of little halls and passages . . . The furniture, old-fashioned rather than old, like the house, was as pleasantly irregular . . . All the movables, from the wardrobes to the chairs and tables, hangings, glasses, even to the pincushions and scent-bottles on the dressing-tables, displayed the same quaint variety. . . .”

Within his eccentric environments, del Toro conceives and consolidates his ideas into precisely crafted feature films for an international viewership. “Spiritually, my life is here,” he commented in 2013. “I exist in this house, really.” Not only is collecting integral to del Toro’s creative process and emotional well-being, but it also drives the plots of many of his films, in which characters reveal their essential natures or meet their destinies via the objects they accumulate, covet, or destroy.

Del Toro locates his voracity for fanatical collecting in childhood. Fascinated by the medical texts, encyclopedias, and art history books his father bought to adorn the family home after winning the lottery, the young Guillermo also added layers of pop culture knowledge as he discovered film, fan magazines, and comic books. Today, del Toro invests considerable intellectual and emotional attention in his collecting, as well as money (he claims to devote half his salary for each film to new acquisitions) and manual labor. He selects, installs, maintains, and, if necessary, fixes every item in his possession.

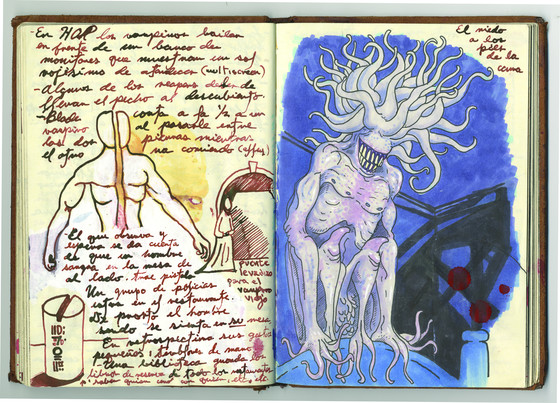

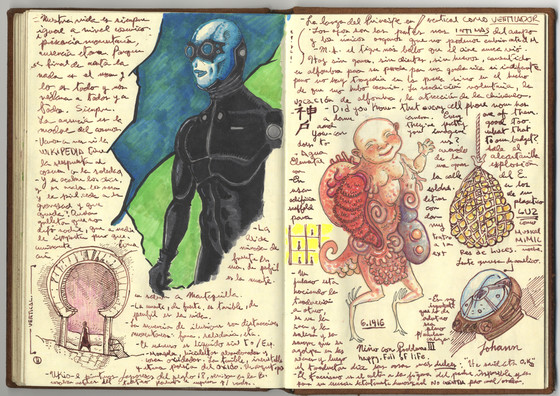

Del Toro’s intellectual curiosity extends well beyond cinema itself to encompass history, politics, literature, architecture, medicine, and occultism. His intimacy with artifacts from a variety of cultural traditions contributes to the palpability of the worlds he creates on film. All aspects of cinematic form—color, sound design, blocking—are calibrated around objects, bodies, and their containers (whether boxes, caskets, costumes, or buildings). Del Toro designs these to exist fully, in three dimensions: “I love the creation of these things—I love the sculpting, I love the coloring. Half the joy is fabricating the world, the creatures.” He lives with full-scale sculpted figures of characters real and imaginary: authors Edgar Allan Poe and H. P. Lovecraft; famous freak-show performers Johnny Eck, Schlitzie, and Hans (Harry Earles); Boris Karloff as Frankenstein’s monster; and Sammael from Hellboy.

Collections have very strong visual presence in del Toro’s films: stacks of specimen jars, shelves of books, rows of statuary. In Pan’s Labyrinth, the Pale Man’s lair is adorned with a painted frieze and piles of children’s shoes, two different representations of his vile appetites. In Crimson Peak, seemingly conventional paintings and photographs portray deceased characters whose spirits may escape the confines of the frame. (The production design departments on del Toro’s projects also sometimes feed his personal collections: If a studio declares a prop too expensive, he pays for half of it and keeps it for himself.) Indeed, objects in his films are more than props; they are manifestations of characters’ worldviews. They also often come to life, even if initially presented in static conditions, forcing characters to react to them instead of simply gazing upon them.

In this way, sometimes humorously and sometimes darkly, del Toro comments on the ocularcentrism of modern museum and film culture. It can be no coincidence that his collection includes many objects and images showing gouged or otherwise compromised eyes. Overseers of varying kinds, whose power is based primarily on empirical observation or surveillance, are likely to encounter difficulties in his films.

In several instances, characters require prosthetic or protective eyewear: Blade and other vampires shield their eyes with sunglasses; Hellboy and Abe Sapien use Schufftein goggles to find the entrance to the Troll Market; Alan McMichael is an optometrist in Crimson Peak. Perhaps the most extraordinary scenes of disordered vision in del Toro’s filmography occur in Pan’s Labyrinth. The film opens with a close-up of Ofelia’s (dead) eye, which becomes our portal to the rest of the narrative, just as Ofelia herself enters a fantasy realm through a statue’s missing eye. In nonhuman characters, eye symbolism becomes even more explicit. The Pale Man, lacking eyes in his face but bearing them in his palms like stigmata, is among the most viscerally affecting monsters in all of cinema.

Teeth are another cranial motif appearing throughout del Toro’s collections and films. He taps into the primal urge to know the world through tasting it; then he alludes to various cultural and religious prohibitions and permissions about what cannot be eaten and what should be savored. To name only a few examples, Jesús Gris is compelled to lick blood from a bathroom floor in Cronos; Ofelia unleashes the Pale Man by eating a forbidden morsel from his banquet table; the tooth fairies in Hellboy II are creatures who can only eat and defecate; and Hannibal Chau, a black-market dealer in Kaiju organs in Pacific Rim, is swallowed whole by one of the creatures and has to cut his way out of its corpse. Teeth are the salient features of the Faun in Pan’s Labyrinth, Sammael in Hellboy, the Reapers in Blade II, and many other characters. What one eats reveals one’s nature and beliefs. Incompatible appetites may cause violent conflict, as recounted in many fairy tales and parables, among them Rubén Dario’s poem “Los motivos del lobo,” which strongly impressed del Toro as a child. Of course, since he works in the medium of cinema, del Toro must rely on visual effects— and the inherent connection between imagery and imagination—to depict ingestion.

As every lover of the medium knows, films are not only seen; they are felt. The power of genre aids this gut-level response, as narrative conventions, sound, lighting, and color all serve to trigger audience expectations and reactions. It is impossible to witness eye gouging or teeth clamping without experiencing a mirroring response to protect our own bodies and to reassure ourselves that we remain intact even while the creatures on-screen are torn apart. Their struggles against death, choreographed in spectacular form, externalize anxieties that are endemic to the human condition. Outside the confines of the movie theater, in which we are safe as spectators, we must confront the fallibility of our senses, brains, and bodies, and our dread of both dying and living. Objects endowed with special properties can link these seemingly incommensurate states: the safety of the moviegoing experience and the cruel uncertainty of reality.

Because such objects have material and existential value, this brings us back to the logic of collecting, and to a perhaps surprising conceptual link between horror films and museums: Both of them emphasize the latent power of objects, whether by bringing them to life or keeping them for posterity. Del Toro’s private collection has been assembled precisely in the space between. It is not only seen but also handled and, at least in metaphorical terms, ingested. Created in this environment, his films are (among other things) lessons in respectful coexistence with powerful, talismanic objects, based on his own experience of living with collections.

Del Toro’s work fits into an art museum for obvious reasons: He is a master craftsman; he is steeped in the history of his medium and in many other disciplines; and he addresses the great themes of human inquiry in the most relevant idioms of our time. But his challenge to the traditional museum is just as interesting. Standards of rarity, value, taste, and skill are never as fixed as institutions would have us believe; they ought to be questioned and reevaluated at regular intervals and from different points of view. When a private collection such as del Toro’s is brought into a public museum, it reanimates the museum and erases hierarchies. “Polluting” the institution with so-called base materials, like an alchemist, del Toro produces gold and, in the form of new knowledge and perspectives on history, achieves a kind of immortality.

This essay is excerpted from the exhibition catalogue. Exhibition catalogues and titles by Guillermo del Toro are available at the LACMA Stores. On Friday, July 29, come to the museum for a rare opportunity to have Guillermo del Toro sign your exhibition catalogue or another title by him purchased at the LACMA Store. This event is first-come, first-served; you may begin lining up at 3 pm. Book signing is limited to two books per person and a receipt as proof-of-purchase from a LACMA Store is required. LACMA Stores open at 11 am. Book signing will end at 6:30 pm. The exhibition opens to the public on August 1.