A gargantuan sculpted head of Frankenstein's monster stands guard over the entrance hall of Bleak House, a labyrinthine home in the suburbs of Los Angeles where Guillermo del Toro keeps his museum-like collection of monster paraphernalia. Stopping visitors in their tracks, the head dominates the hall like the sun in the summer sky, and everything else seems to radiate out from it. Nearby in the kitchen, del Toro is discussing his acquisition of the piece.

"Mike Hill made it, he made it that size to have the same impact that seeing the original monster on a movie screen would have had for audiences back in the day. But he didn't want to sell it." Del Toro explained to Hill that he had the perfect place for it. Hill visited and agreed. "It needed to be that exact height," del Toro continues. "It's the same height as a cinema screen. That's what gives it maximum impact."

The impact of monsters is an important topic to del Toro. He credits the monsters he discovered in pulp cinema magazines for liberating him as a child in Mexico. In them, he found what he calls an "immense minority," and one that was not evil as he had been led to believe. They were outcasts from society, but there was a pathos to them that he could empathize with. "It's as if they were saying, we accept you, we freaks and monsters give you welcome."

.jpg)

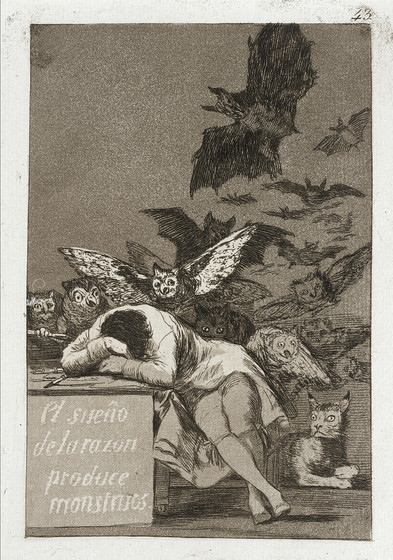

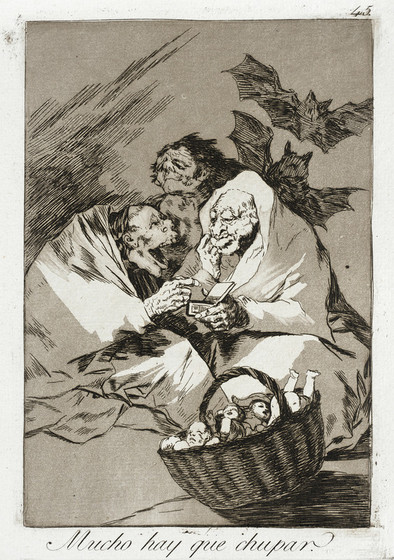

Del Toro sees monsters as the patron saints of misfits. "We are all outcasts from paradise," he says, and goes on to define two poles in art that have evolved in relation to our universal position as a consequence. One celebrates mankind as God's greatest creation. The other sees us as abandoned children. Monsters come from the latter, he explains, where they represent an image of humanity itself, complete with all its imperfections. "Their struggle as outcasts is the existential struggle of the human condition . . . they are a twisted reflection, like a funhouse mirror, and within that reflection there are aspects of yourself you don't normally see." As foreign as they might seem, monsters are our shadowy twins. We create monsters. They may produce shock and horror, but in the process they also define and complete us. And it has been this way for all of human history, because, in one form or another, monsters have constantly been with us.

Monstrosity has always been more concept than reality. Accusations of monstrous appearance have been a traditional means of defining an outsider, and have long served as part of a basic system of alterity which separates the Self—one's social, ethnic, political, or religious group—from the Other, who represents the opposition. By using a simple strategy of polar inversion, the Self claims superiority by appropriating an ideal set of virtues, while projecting corresponding vices onto the Other. If we are pious, they are sacrilegious; we are kind, they are cruel; we are civilized, they are barbaric; and if we are beautiful, they are monstrous. But of all the means by which one might construct an outsider, monstrous appearance is the most effective, because the monster's body becomes a text on which is inscribed the immediate and unmistakable message that they exist outside of our natural order. With the monster, difference is clear and obvious. Nothing conveys the status of the Other like monstrosity.

It has been this way since the ancient world, when monstrous types were such a common topic of discourse that they are sometimes still referred to as the Plinian races, after the Roman encyclopedist who catalogued them in book seven of his Natural History in 77 AD. Pliny did not invent his monsters, however. He simply compiled them from even older sources. Some are found as far back as Babylon, and they were a familiar topic in Ancient Greece, where it was common to speculate on the degraded nature of humanity in the far reaches of the world. To the Greeks, outsiders were literally barbarians: in Greek usage, barbaros referred to exotic people of a different culture, who were thought to be morally and physically inferior. The further one ventured from the Hellenic world, the more deformed and degraded they became, until they crossed the border of what might reasonably define humanity and assumed monstrous forms.

By the time Pliny compiled all of these sources, the corpus further included people in Libya who lacked heads, but instead had their faces in the centers of their chests (Blemmyae); a race of humans with horses' hooves instead of feet in the Baltic (Hippopodes); and women completely covered in hair on islands west of Africa (Gorgades). And these are but a sample of the fuller picture: the Greco-Roman world was literally encircled by monsters, like an island of civilization in a sea of deformed beings. That the people in the regions discussed looked absolutely nothing like what was described was not strictly relevant. Their status as monsters was based on a mythic level of thinking, the intention of which was to create images that connoted what it meant to be an outsider, and this gave these forms enduring value.

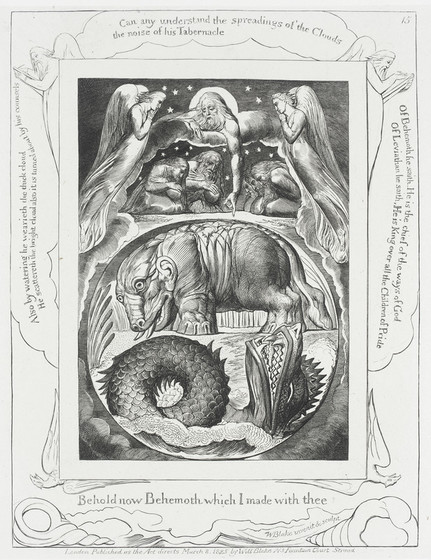

Early Christian writers not only accepted these monstrous races, they gave added weight to them by focusing on their moralizing potential: in addition to these creatures being physically and culturally inferior, their abnormalities were a sign from God. Monsters were believed to exist in a fallen state of grace. They had been rejected by God, and most likely descended from negative characters like Cain or Ham. A moral philosophy evolved in which forms considered unnatural—be they mythic monsters or authentic abnormal births—were equated with Divine wrath. Early Church fathers like St. Augustine believed that people of monstrous appearance were being punished for past sins, and served as symbols to frighten the rest of humanity into obedience, and Isidore of Seville explained that God used monsters to signify an impending misfortune. Monstrous appearance became part of God's plan, a warning from on high about the consequences of sin and faithlessness. Our modern word monster is in fact based on this very idea, derived from the Latin root monere, meaning to warn.

Passed from generation to generation, the ancient corpus of monsters populated bestiaries and wandered among the drolleries of illuminated manuscripts. Eventually many of these queer beings popped up in medieval travel accounts. The Cynocephali, for example, were mentioned by Giovanni de Pian de Carpini, a 13th-century Franciscan monk who traveled through Central Asia during the period of Mongol domination. He claimed to have encountered the dog-headed men, and said they barked every third word. A century later, another Franciscan, Odoric of Pordone, also mentioned seeing dog-headed people when he traveled eastward to China. Soon after the most famous of all the medieval travel writers, John Mandeville, likewise claimed to see dog-headed people, as well as pretty much the entire pantheon of Plinian races.

There is ample evidence that Mandeville's account may be partly or wholly fictionalized, but both Pian and Odoric authentically traveled to the places they wrote about. They were telling outright lies about seeing dog-headed people, but had no choice if they wanted their accounts conform to the expectations of their audience. The idea that exotic places were populated by monsters was so engrained that to tell the truth, that no monsters existed, would be to seriously damage the credibility of a traveler's tale. In effect, anyone returning from a far corner of the world had to lie and claim that monsters were sighted—and thus perpetuate the myth—in order to be taken seriously.

Did Dr. Paul Koudounaris's edited excerpt whet your appetite? Learn more about the concept of monstrosity in the publication accompanying the exhibition. On August 11, Dr. Koudounaris will lead a tour focusing on the cultural history and significance of monsters and the monstrous. This event has reached full capacity, but you can tune in to LACMA’s Facebook Live broadcast at 7 pm tomorrow!