One of the most enjoyable and enlightening aspects of my job is sharing historical prints and drawings from LACMA’s collection with contemporary artists. Their approach to looking at art of the past is different from the academic manner of most curators and art historians, which tends to focus on stylistic innovation, historical relevance, or technique. While these issues may be of interest to many artists, as makers they bring personal hands-on experience and curiosity (as well as knowledge) to the encounter that bring the works “to life” in fresh and unique ways.

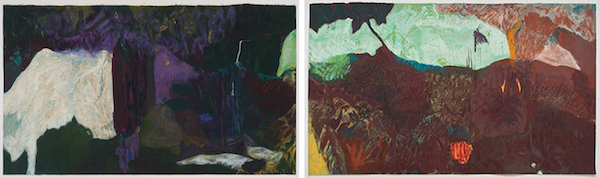

Los Angeles-based artist Mimi Lauter recently visited the Prints and Drawings collection to look at etchings by James Ensor, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí, woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer, Edvard Munch, and Käthe Kollwitz, and drawings by Odilon Redon, Richard Pousette-Dart, and Alfonso Ossorio (to name a few). She curated the list herself using LACMA’s collections online and including works by artists she has long admired but also works that appealed to her because of content or technique. The oldest work was an early 15th century Book of Hours and one of the more recent a pastel by Will Henry Stevens from 1947, both works in the collection that I never paid much attention to but saw and appreciated in a different way after looking at them with Mimi.

After our second two-hour session, Mimi agreed to sit down and share her thoughts on her first experience in a Prints and Drawings study room.

(1).jpg)

Why is it important for contemporary artists to look at historical works of art?

My own work deals with a particular lineage and is interested in ways that lineage develops. I don’t think about having a direct dialogue with my contemporaries necessarily. While I think it’s incredibly important to be aware of the conversations taking place, I’m more interested in not always fitting in and trying to find my own interpretation. The way I go about it is not by looking forward but actually looking back. Painting and especially drawing are the oldest forms of expression, and it’s precisely because they’re so old that you’re always in dialogue with the past. I think of it in terms of jazz. There’s a melody or a moment in the music that you hear in the very beginning and then it takes off, something happens, and you return to it again. It repeats itself and becomes richer and more exciting each time. It’s something familiar that becomes heavier and filled with more context.

How would you describe your experience of looking at works on paper from LACMA’s collection in a study center environment?

It’s a very different experience looking at art in a museum within an exhibition format than sitting with it and performing an act of research. It’s like reading a book and trying to understand something deeper. It’s more intimate and private, not about the spectacle at all. It’s really about learning. I go to museums with the idea of learning but it’s different when you’re sitting down and you have all the time you need. I mean even touching it is kind of exciting, right? It doesn’t have that distance.

Drawing is so immediate and has a relationship to a cognitive process rather than a physical one the way that painting does. It’s about active engaging and as an artist I’m trying to think about what the artist was thinking. If you’re sitting with it the way that they were sitting with it, it’s a very different thing than it being in a curated space. You’re kind of getting into their brain, trying to figure out what happened when they made it.

You have worked exclusively in pastel for several years. Can you discuss the importance and relevance of drawing to your practice?

I was a painter and started using pastel as a technical means to try and understand painting. In school we’re taught that painting is the emphasis and drawing fits somewhere around that. I wasn’t able to develop my relationship to drawing as an independent medium with a complex history until much later, and I’ve had to do it on my own. There’s a certain type of intimacy with drawing. It’s always an accumulation of many marks, never one gesture, and that lead to a different relationship with time. It’s both immediate but slow. Drawing is how we’re thinking, not how we are physically responding to something.

I had a wonderful experience studying works in LACMA’s Prints and Drawings collection. I think that’s ultimately what artists need to be doing . . . just being their own best researchers.