Charles White recognized the power of music to move the human spirit and sought to convey this power to the viewer in his painted works. The artist spoke lovingly about music’s expressive potential in evoking emotion, dignity, soul, and human connection. White found that “music affected me so perfectly, in a way that touched the heart more directly than any other art—the dignity, the outpouring of tenderness, the social and comradely feelings, and humanity of the people.” White depicted many famous African-American musical figures in works of various media and his masterful drawings were included in a number of music books and featured on album covers.

.jpg)

In his tempera painting Gospel Singers, the architectural elements of a church frame the two musicians while the vibrant colors of their garments stand out against the multicolor panels of the stained glass windows behind them. There are strong resonances in this work with some of White’s photographs of musicians in Washington Square Park. Though White painted from memory rather than directly from the photos, the figures in the painting are clearly inspired by his informal photographic explorations.

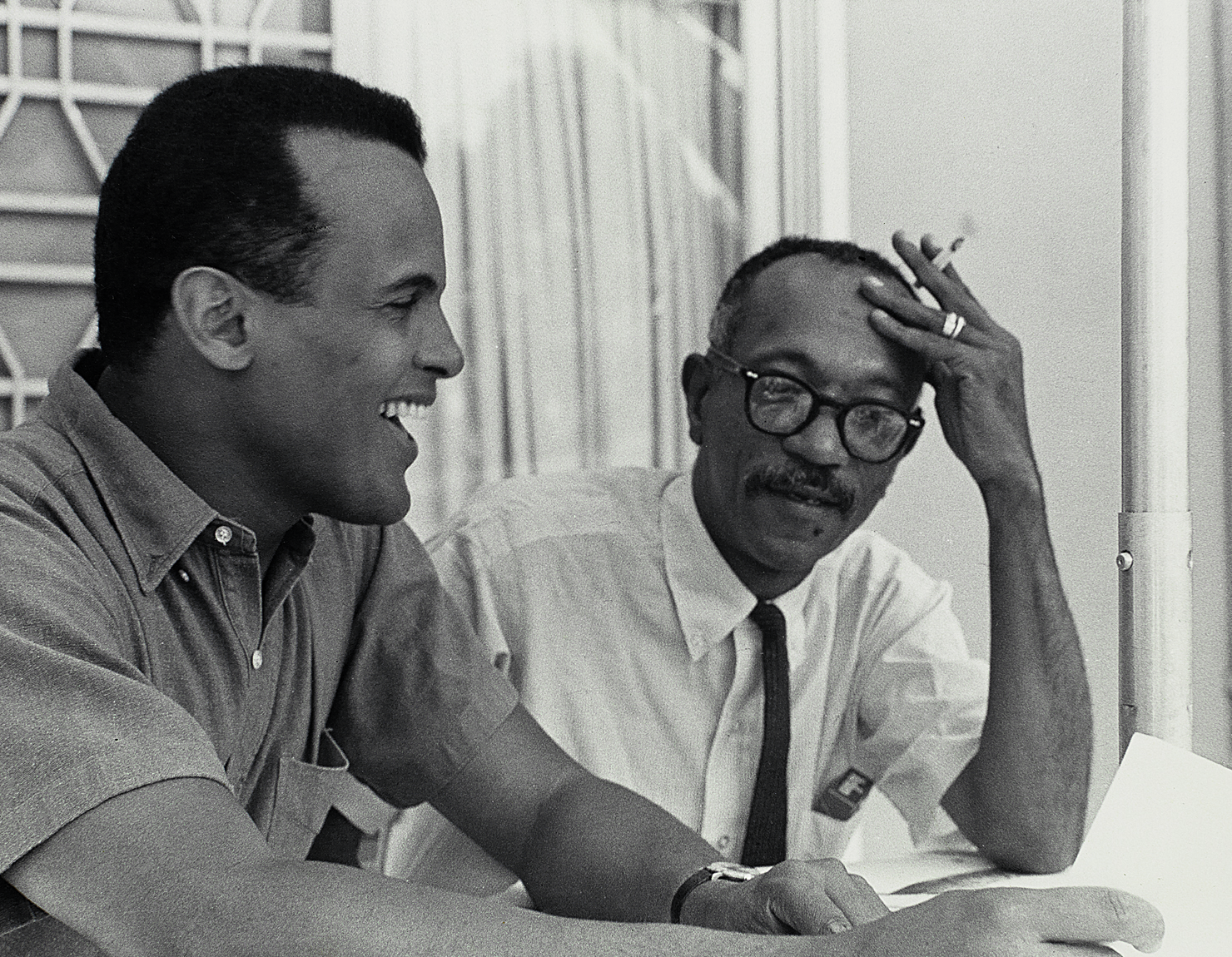

Over the course of his career, White was close friends with a great number of musicians and artists, some of whom he depicted in his work. One such friend was Harry Belafonte, who appeared in a number of White’s works, such as Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte), Voice of Jericho [Folksinger], and J’Accuse #6. White also did a number of drawings that were published in Belafonte’s 1962 book Songs Belafonte Sings. The two even traveled together while Belafonte was on tour, bringing White into contact with other renowned musicians, such as South African singer and civil rights activist Miriam Makeba.

Blues singers featured as quite a number of White’s musical subjects. Growing up in Chicago, the artist had family in Mississippi and found powerful inspiration from and connection with African-American spiritual tradition in the South. In his 1950 painting of legendary blues singer Bessie Smith, White portrays Smith as radiant, almost glowing, and seemingly mid-song, with her delicate yet powerful hands raised in front of her.

White did a number of drawings for a movie about blues and folk singer Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter in 1976. Leadbelly also takes center stage in White’s 1952 painting Goodnight Irene. Harry Belafonte purchased this work from White and used it as the album cover for his multi-cd recording The Long Road to Freedom, a project Belafonte started in the late 50s and finally released in 2001.

Charles White’s drawings appeared on the album covers of many jazz records as well. White was known to visit some musicians in their studios, deriving inspiration for his drawings from their music. White produced album covers throughout the 1950s while based in New York and continued this work into the late 1970s during his time in Los Angeles. Spirituals, a powerful portrayal of a reverent young man holding his hands forth in prayer, even landed the artist a Grammy nomination for Best Album Cover – Graphic Arts in 1965 for its reproduction on the cover of Contemporary American Masterpieces: Gould: Spirituals for Orchestra; Copland: Dance Symphony.

As much as the spirit of music moved Charles White, we invite you to join us at the museum for Jazz at LACMA, free of charge on Friday evenings from April 26 until November.

Charles White's work can be viewed in two current LACMA exhibitions, Charles White: A Retrospective (through June 9) at LACMA, and Life Model: Charles White and His Students (through September 15) at Charles White Elementary School.