Contemporary Art is pleased to announce the Art Here and Now (AHAN): Studio Forum artists of 2020—rafa esparza, EJ Hill, Simphiwe Ndzube, Gabriella Sanchez, and Cauleen Smith. We are excited that LACMA's Board of Trustees has approved the acquisition of work by each of these five artists.

As a Mellon Undergraduate Curatorial Fellow, I have had the opportunity to meet and work with several artists in Los Angeles since I began my fellowship at the museum two summers ago. This year in the Contemporary Art Department, I have been mentored by Terri and Michael Smooke Curator and Department Head of Contemporary Art Rita Gonzalez, and Curator of Contemporary Art Christine Y. Kim. AHAN is an ongoing LACMA initiative that I find particularly significant because it does more than simply provide international exposure to emerging artists in Los Angeles. As an acquisition fund, AHAN: Studio Forum highlights emerging talent in the museum’s local community. Guided by Rita and Christine over the course of six months, I corresponded with the artists and worked as their liaison. From the studio visits in January to the forum in February and from the acquisition decisions to this announcement, there has been a dramatic shift in the tone of the world. During the two lively days of studio visits, AHAN members and our LACMA team listened to the artists speak passionately about their practices and work. The group’s conversations about art, activism, institutional accountability, and accessibility set a memorable tone that left me energized and excited.

Since then, we have all had to face a new reality, and examine the role of art in the public sphere. With global museum closures come complex conversations about accessibility and artists’ voices. Experiences like the studio visits have become memories that we must consider as we adjust to the re-opening of art spaces. For this year’s announcement, I conducted interviews with each artist about their practice and the AHAN acquisition of their work. In light of the Safer at Home order, and the most recent outcries of the Black Lives Matter movement, I found these exchanges incredibly intimate and humbling. From my perspective, talking about new works coming into LACMA’s collection made me consider the future when we can be around art again, and what role we all have in supporting our local artists and communities of color in Los Angeles.

rafa esparza

As a Los Angeles native, what does it mean for you to have work in LACMA's collection?

Having my work in LACMA’s creative genealogy which is historically Anglo, reminds me of the work of ASCO and seeing it in LACMA’s 2008 exhibition Phantom Sighting: Art after the Chicano Movement. When I was at East Los Angeles College, ASCO was like a myth, and there was no real scholarship at least that was accessible to see the breadth of their work, objects, and archives. When I saw that exhibition, it felt like something that should’ve happened a long time ago, and for me it marks a special moment of growth of visibility in the discourse among brown artists. The incoherence of this moment makes it exciting to have my work acquired by LACMA. What we are experiencing now is malleable and can change and evolve part of a collection index to catch up to this moment.

Are you working on any public performances or collaborations that you could tell us about?

I have been collecting my saliva since May 15 and I am planning on using it in a performance where I will juggle balls of my saliva. I see it like the body as an orbit, thinking about what goes in and out, what’s unseen and how little we know our bodies. Right now we are having conversations about who we are in history and how our bodies could be carrying a threatening virus. I think about this as a performance artist and how that will change in our interactions with each other now. Right now there is a lot of fear and we are asking ourselves questions out of heightened emotions. I am also working on a project called “In Plain Sight” which I co-initiated with fellow performance artist Cassils. It is meant to bring visibility to the number of migrant detention centers in the country. We are planning a national spectacle this summer to call out the number of migrant detention centers in the country.

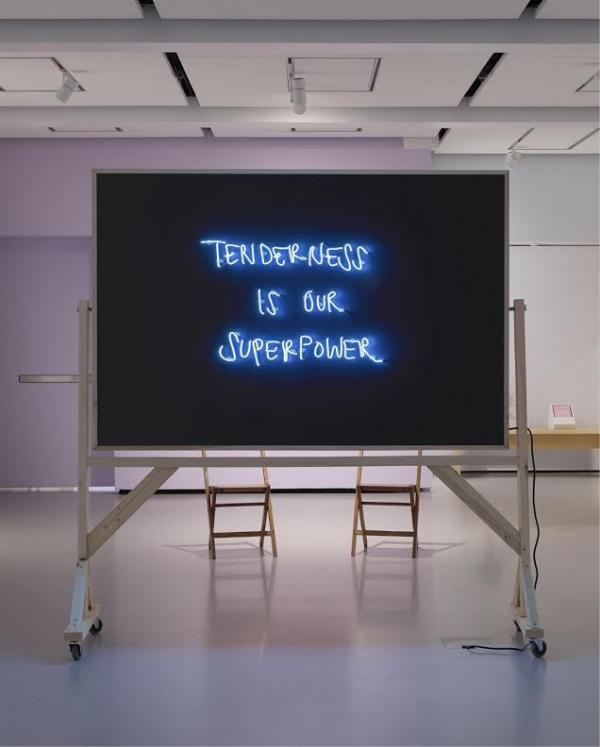

EJ Hill

Do you have a favorite work of art in LACMA's collection or a favorite exhibition that comes to mind when you think of LACMA?

I think there is something really wonderful about Urban Light being this kind of beacon even for the people who never step foot inside of the museum. There’s something in it’s legibility, reading it and understanding it immediately. It's so L.A. in many ways. It does not rely on art historical precedent or that particular type of language. You can see a bunch of vintage street lamps arranged in groups by height outside, and get it. The amount of times I've just seen people interacting with it in a very sincere, real way shows the importance of art on the level of the People with a capital P. I think about being a part of Chris Burden’s history in L.A. with performance that sort of leans into sculpture. Burden has been a big influence for me in how I have approached performance, approached sculpture and installation, so there is a link there.

Retrospectively, do you see a relationship between your work in endurance, namely Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria, (2018) that was included in Made in L.A. at the Hammer Museum, and the isolation during the shelter-at-home order during the coronavirus pandemic?

At the beginning of this, I joked with a few friends that I'm an expert of silence, isolation, and extended grueling periods, which is really only a half joke because the other half is 100% real. At first I thought I might be better prepared to enter into something like this because of my previous performance work, especially at the Hammer. For Excellentia, Mollitia, Victoria, I was inside for hours at a time, not speaking to anyone for three months. That's like what we're doing now, of course under different circumstances, but there are absolutely parallels. I have been struggling with how to show up and be supportive for those who are struggling with this isolation and the accelerating pace of things. I quite honestly found comfort in isolation and as difficult as that project was, I embarked on it because I knew that it would be healing and restorative for me at a time that I needed it most. Now isolation comes with the suffering and death of so many other people, which is obviously not the ideal version of having a reflective time. But it's what we have and I am hoping that people might be able to lean into the silence of solitude long enough to experience grounding, healing, and tenderness.

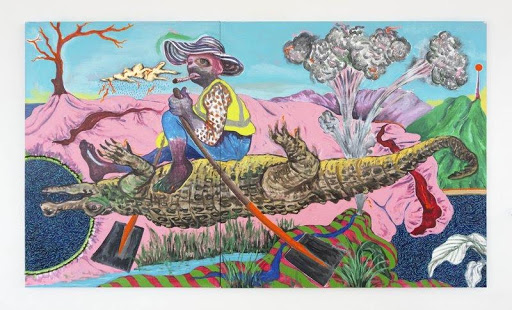

Simphiwe Ndzube

What has been the most profound change or evolution in your work since you relocated from your native South Africa to Southern California?

I feel immense gratitude for having been recognized by LACMA and other U.S. museums at such an early stage in my career. One of the major things that has changed in my work is that I’ve been dealing with my subject material—the ordinary South African black experience—from a distance. What this distance has allowed is an open-ended space of experimentation and freedom that doesn’t adhere to any sort of absolute truth. I’ve embraced the experience of Los Angeles in terms of light, for example, by taking inspiration from (David) Hockney's colors and use of light. My work used to be shy; it’s no longer shy; it's fun and playful.

If your work Bhekizwe, The Alligator Rider could be installed in any context, or paired or grouped with any work of art in LACMA's collection, what would that be or look like?

I would want it to be paired with Back Seat Dodge ’38 by Edward Kienholz because of the absurdity of that work and the absurdity of my piece. Human nature, a desire for movement, fantasy, profanity, and lightness are captured in both.

Gabriella Sanchez

As a Los Angeles native, what does it mean for you to have work in LACMA's collection? Do you have a favorite work of art in LACMA's collection or a favorite exhibition that comes to mind when you think of LACMA?

It means I can bring my family to see my work when it’s exhibited in our hometown. It means they can walk into this space and know they’ve contributed to the life of this museum just as they’ve contributed to my life for this work, as with all my work, it is a labor of generations. A favorite work of mine in LACMA’s collection is Diego Rivera’s painting Día de Flores. One year when I was in college, I bought my mom a print version of one of his flower vendor paintings from a gift shop. I framed it and gave it to her so she could have it and it could be hers. After that, whenever my mom and I would see one of Diego Rivera’s flower vendor paintings my mom would say “there’s my painting” or I’d tell her “there’s your painting.” So, Día de Flores is my favorite piece in this collection because it belongs to my mother.

If your work Down is Up could be installed in any context, or paired or grouped with any work(s) of art in LACMA's collection, what would that be or look like?

Showing my piece alongside John Baldessari’s work, specifically a piece like his print Studio in tandem with a Lorna Simpson piece like Indifferent or Lived in the Neighborhood would be an incredible dream realized. That’s a conversation between works that I’ve privately imagined as I see my work pulling on threads of thought I believe each of their work also connects to but each of us using those threads to make something quite varied from the other. Each of us in our own way framing and reframing, adding and subtracting in an effort to show the systems we live and communicate within. Essentially, mapping the subconscious through image responses that in a way reveals the artist just as much as the viewer. Damn! Ya, that’d be a dream.

Cauleen Smith

Do you have a favorite work of art in LACMA's collection? How does/why did it speak to you?

Absolutely: De Style, 1993, Kerry James Marshall. I moved to Los Angeles in 1994 to attend film school at UCLA. I remember the afternoon that I discovered Kerry’s painting, hanging in a transitional space between two larger galleries. There was one bench. I planted myself there for hours just marveling at the barbershop cosmos. And over the course of my four years in grad school, I would visit this painting whenever I confronted crises or challenges. I sat in front of Kerry’s painting and told myself over and over that if this painting could be here, in this museum, then surely, surely I could just make it through grad school. Years later I attended a talk in which KJM (Kerry James Marshall) spoke of this painting. He said that as a kid on field trips to LACMA seeing Charles White’s work in the museum was revelatory for him. It signaled to him that he too could be an artist. His private goal was to also have a painting hang in LACMA. He said that LACMA’s acquisition of this painting was a milestone for him. A kind of validation of his actuality as a painter and artist. When I heard that I burst into tears. My encounter with his painting had done the same for me. I am so grateful for it and to Kerry James Marshall and to Charles White. And so now you know how much it means to me that Epistrophy will live in your collection.

Could you tell us about your upcoming exhibition at LACMA, how it is different here from the one at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Philadelphia?

Each reconfiguration of the show teaches me something about the ways these works were initially conceived to live together and the possible ways that they are able to live apart and separate from one another. This show is very much about the relationship between objects, videos, sound, light, space, and environment. So while the pieces are no longer able to push a spectator through three separate chambers which calibrate tone, pacing, and attention differently, the works instead make a dimensional, experimental labyrinth. It’s a maze that is easy to escape, but my hope is that no one wants to.