As the Russian invasion of Ukraine continues and the latter’s museums and their holdings continue to be at risk, it is all the more important for museums elsewhere to safeguard and share works by artists born or active in Ukraine. We are proud that a number of works by four such artists are currently on view in the Modern Art Galleries at LACMA.

Ukraine, no doubt because of its crossroads location and extensive access to the Black Sea, was historically contested. Throughout most of the 19th century, it was controlled by either the Austro-Hungarian or the Russian Empire. The Ukrainian People’s Republic was formed in the early 20th century; in 1922 it became part of the Soviet Union. Ukraine gained official independence again in 1991, with the collapse of the USSR. A number of well-known early-20th-century artists who made significant contributions to the development of Modern art and who are typically grouped under the rubric “Russian avant-garde” were in fact born, trained, or worked in what is now Ukraine.

Born in current-day Poland (at the time a part of the Russian Empire), Alexandra Exter (1882–1949) graduated from art school in Kyiv, Ukraine. Though from 1908–14 she was based in Paris—then a magnet for forward-looking artists from across Europe and the Americas—Exter returned frequently to Kyiv and also traveled to Moscow, connecting those eastern capitals to avant-garde vocabularies then prevalent in Paris and sharing Cubist and Futurist ideas with eastern peers. Exter spent the years immediately before, during, and after the 1917 Russian Revolution in the east: she lived in Moscow from 1916–17, taught art in Odesa, Ukraine, from 1917–18, and taught in Kyiv, where her studio also produced decorations for various revolutionary festivals, from 1918–21. Exter was likewise involved with experimental theater design in Moscow, where she returned in 1921; there her activities expanded to include fashion and film design. In 1924 she moved permanently to Paris.

In 1926 Exter was commissioned to design a group of 40 marionettes meant to star in a film (never realized) by Peter Gad. Evening Dress (1926) is one of the 20 surviving marionettes from this series. All are approximately two feet tall with very sophisticated designs incorporating Cubist motifs, abstract shapes, and operational mechanics. With works like Evening Dress, which combines functionality, non-art materials, including cardboard and plastic, and pure geometric shapes, Exter was important in popularizing abstraction.

Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964) was born in Kyiv and studied at the School of Art there before moving to Moscow in 1906 and, two years later, to Paris. He quickly began his association with various Cubists, finding radical possibilities for sculpture in Cubism’s formal vocabulary. Archipenko was a pioneer in using the void as an essential sculptural element in his bronzes, even before Pablo Picasso’s famed sheet-metal Guitar (1914). Archipenko’s Dance (version C), conceived in 1912–13, boldly explores the relationship between form and space with two figures, one seated, one standing; the figures touch only where their raised hands meet, thus framing a large, central void. Archipenko scholar Katherine Janszky Michaelson has written that his conception of the sculpture as a framing element for space—with space not only taking on an active role but becoming the very reason for the sculpture—was unprecedented at the time. Dance (version C) bears a striking similarity in both subject and form to Henri Matisse's celebrated Dance (I) (1909), which Archipenko no doubt saw while living in Paris. Executed with a more pronounced angularity than Matisse's painting and incorporating the contemporary, Futurist notion of dynamism, Dance (version C) celebrates the body in motion and gives equal value to the space enclosed by the figures and the figures themselves.

With the outbreak of World War I, Archipenko relocated to the south of France, where he blended elements of Cubism with aspects of Constructivism in a novel synthesis of painting and sculpture he called “sculpto-painting.” Woman with Hat (1916) is a beautiful example of this type of work. With its broad planes of vibrant color and surface pattern, Woman with Hat literally comes off the wall. By 1922, Archipenko declared these hybrid works to be his most important; today they are regarded as his most original contribution to modern sculpture. Only half of his 40 unique sculpto-paintings have survived, with only a few examples in the United States.

Still Life with Book and Vase on Table (1918, cast 1960) is a sculpto-painting cast in bronze. Archipenko first created this still life with papier mâché, wood, and plaster. Concerned that these materials were prone to decay, he rendered the same composition in bronze more than four decades later, by which time he had developed specific chemical formulas for creating a variety of toned patinas for the metal surface.

Archipenko’s Walking Soldier (1917, cast 1967) is his only work to reference World War I directly. It combines twisting conical forms interlocked to create an image of a soldier walking with a rifle at his side. The sweeping curve of his torso stands in opposition to the linearity of his weapon, while the body’s dense block of bronze contradicts his emaciated legs. Each inward curve leads to a convex plane, yet, despite this tension, the incongruous elements serve to unite the figure. According to Archipenko, “all positive and negative by the nature of polarity eventually become one. There is no concave form without a convex; there is no convex without a concave. Both elements are fused into one significant ensemble. In the creative process, as in life itself, the reality of the negative is a conceptual imprint of the absent positive.”

Archipenko exhibited works at the famed Armory Show in New York in 1913. He moved to Berlin in 1921 before emigrating to the United States in 1923.

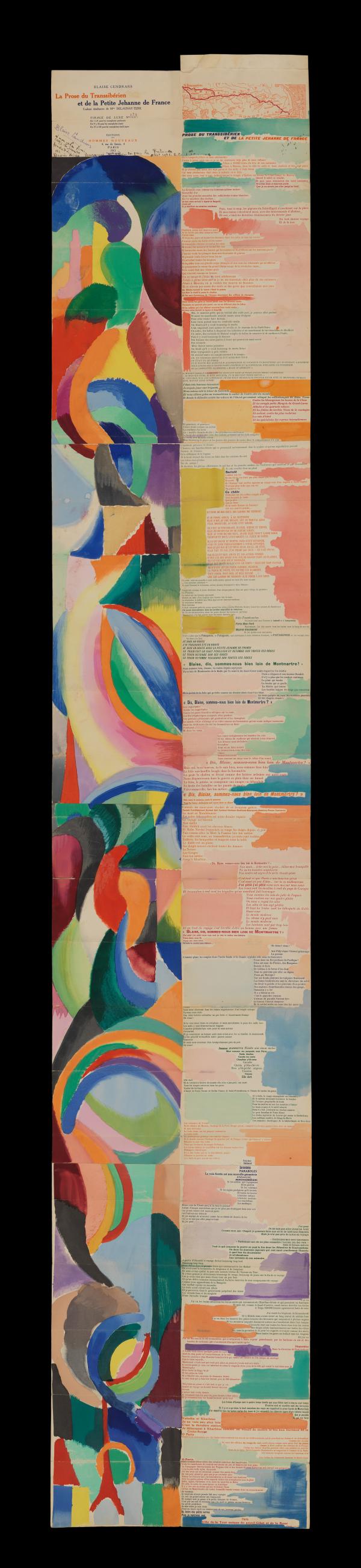

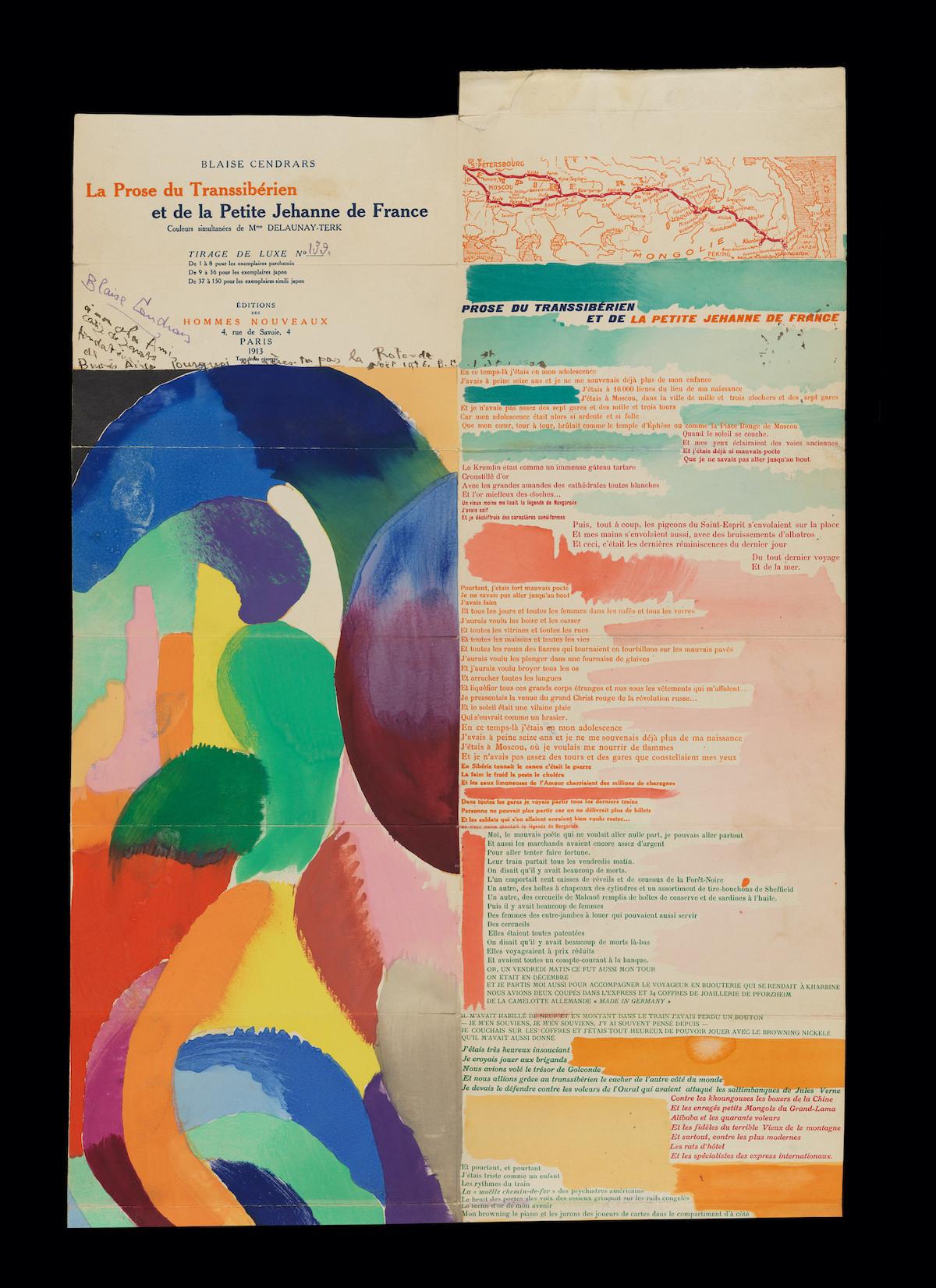

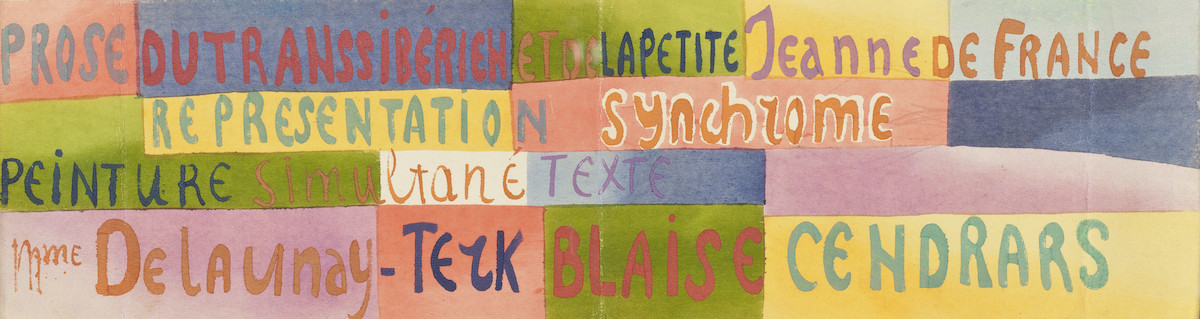

Born in central Ukraine, Sonia Delaunay-Terk (1885–1979) studied in Germany and Paris, where she settled in 1906. She is best known for forging a link between the fine and applied arts (similar to the approach of the Bauhaus), making important contributions as a painter, printmaker, interior designer, and textile and fashion designer. She also did a number of book collaborations, the most famous of which is La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913), with poet Blaise Cendrars. Delaunay-Terk’s visual component of this striking work reflects “Simultanism”—a fusion of abstract forms in dynamic colors with the dynamism of modern (especially urban) life—which she developed with her husband, painter Robert Delaunay. Advertised as “the first simultaneous book,” La Prose du Transsibérien is a poem in free verse by Cendrars paired with pochoir (stencil) images by Delaunay-Terk. This picture-poem, conceived as a dialogue between the text and its visual accompaniment of shapes and colors, is meant to be seen and read at the same time, like a conductor reads an orchestral score or the way we both see and read a poster. Cendrars’ work is a memory poem (about his youth in Russia), but the story is recalled as if it were happening at the moment of recollection. To look at the brilliantly printed original book, with the parallel columns of color and text, one seems to swim through a river of words and images, or—perhaps more accurately—move along a long, meandering, train route.

This groundbreaking collaboration between Delaunay-Terk and Cendrars was announced by a small oblong Prospectus and then sold folded up inside a Portfolio Cover (both 1913). All three components of La Prose du Transsibérien reflect Delauney-Terk’s love of pure color combined with text. The examples in LACMA’s collection have intriguing provenances (or previous ownership). LACMA’s Prospectus was given by Delaunay-Terk to Walter Pach, the organizer of the 1913 Armory Show in New York, and was acquired in the 1980s by art historian and author William Agee. The artist gave our Portfolio Cover to well-known graphic designer Elaine Lustig Cohen, whose daughter Tamar Cohen subsequently owned it (and who donated many examples of her mother’s work to LACMA). And LACMA’s La Prose du Transsibérien was inscribed by Cendrars to the Chilean artist Manuel Ortiz de Zárate, who introduced Diego Rivera to Picasso in Paris in 1914.

Janet Sobel (1894–1968) was born Jennie Lechovsky in Katerynoslav (now Dnipro), Ukraine—about 250 miles southeast of Kyiv—and emigrated to the United States in 1908 after her father was killed in an anti-Semitic pogrom. She settled with her family in the Brighton Beach neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, and married fellow Ukrainian immigrant Max Sobel two years later, at the age of 16. Unlike Exter, Archipenko, and Delaunay-Terk, who studied art and began their practices early in life, Sobel was self-taught and didn’t begin making art until her mid-40s, after raising five children. Her early work—often painted on pieces of mail, scraps of paper, and cardboard from the dry cleaners—drew on childhood memories and the patterns and motifs of Ukrainian folk art. She soon began experimenting with enamel paint and glass pipettes from her husband’s jewelry manufacturing business, dripping and blowing skeins of pigment onto canvas or board to create filigreed, allover patterns. As in The Burning Bush (1944), faces and other figurative elements often emerge from her otherwise abstract, web-like compositions.

Sobel quickly gained attention for her work; she had a solo exhibition at Puma Gallery in New York in 1944, the influential art collector Peggy Guggenheim exhibited it in group and solo shows at her Art of This Century gallery in 1945 and 1946, respectively (The Burning Bush was included in both of the artist’s monographic exhibitions), and it influenced the drip technique for which Abstract Expressionist artist Jackson Pollock later became known.

All of these striking works by important modernist artists with roots in Ukraine reflect how connected the country was to the 20th-century avant-garde; they are currently on view in the Modern Art Galleries in BCAM, Level 3.