Beeple’s Diffuse Control is an image-generating sculpture that invites visitors to collaborate with artificial intelligence. A custom website allows museum visitors to interact with the AI generative system, which transforms images of select public domain artworks from LACMA’s permanent collection, organized in five iterations. The sculpture—comprising 12 large video screens—displays the resulting images, allowing the audience to remix this new creation in real time. Diffuse Control by Beeple is on view through January 4, 2026.

Here, Jiayi Hou, Cc Foundation and David Chau Fellow, reflects on artworks selected for the iteration Living Patterns.

Living Patterns features six pattern works from LACMA's permanent collection, spanning the 14th to 19th centuries and representing diverse cultural traditions. Though separated by geography and time, these works form a cohesive visual dialogue when experienced through the Diffuse Control installation.

The magic of this artificial intelligence–driven experience lies in its ability to animate what was once static. Flowers painted on ceramic tiles perpetually bloom; geometric motifs pulse and shift. These works achieve what their original designers might have imagined but never thought possible—patterns truly coming to life before our eyes.

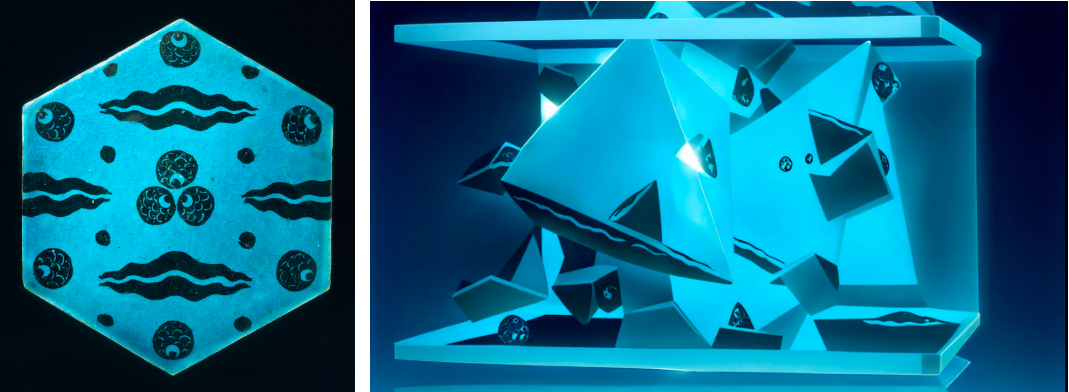

Yet Diffuse Control doesn't simply animate; it interprets. The Syrian tile from Ottoman Damascus was decorated in the period's signature turquoise and black with circular and wavy patterns suggesting leopard spots and tiger stripes. The AI program reads the turquoise as luminous, transforming the tile into something unexpectedly futuristic, glowing with electric blue light that bridges centuries.

Moreover, these decorative objects—plates, quilts, tiles—contain more cultural and historical information than their ornamental nature might suggest. Technical innovations and economic prosperity facilitated massive Ottoman building projects, for instance, which adapted Iznik's signature palette, originally developed for tablewares, onto monumental architectural surfaces like the Turkish four-tile panel suggests. Similarly, the Chinese blue-and-white Yuan plate, with its Buddhist patterns influenced by Persian metalwork and Mongol or Tatar embroideries, was likely created for Silk Road trade, demonstrating how international commerce shaped ceramic techniques and visual vocabularies.

We stand at another technological threshold. Does AI promise similar disruption as these historical innovations that spurred economic growth and transformed labor practices? Through Living Patterns, we can contemplate: what artistic and aesthetic revolutions await us, and what will their aftermath reveal about our own moment in history?